| (26 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

{{UGent_Belgium}} | {{UGent_Belgium}} | ||

| − | <html > | + | <html> |

| − | < | + | <div class="container"> |

| − | < | + | <h1> Filament </h1> |

| − | <p> | + | <br> |

| + | <h2> Overview </h2> | ||

| + | <p> In the filament work package, we tried to produce a plastic filament that’s activated and susceptible to biological appendages. The filament can subsequently be used for printing the desired 3D structure. | ||

| + | PLA (polylactic acid) was chosen as basic plastic carrier because of its biodegradability, optimal melting temperature, and general easy-to-print characteristics. | ||

| + | In order to enhance the function of the PLA, i.e. improve the condensation capacity, we needed to attach biological nucleation proteins to the filament. In order to get the proteins attached to the final structure, either purified or expressed on the membrane of whole cells, a moiety needs to be present in order for the filament to capture them, bind them and keep them there (even while rinsing, or in flooded conditions). </p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/d/df/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament1.png" alt="fig1" height="266" width="800" align="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>General overview; 3D printed structure that's activated with biotin, will be succeptible for adhesion of proteins via biotin-avidin complexation</i></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| − | < | + | <br> |

| − | <div class=" | + | <p>We chose to assess the biotin-(strept)avidin complex, since it’s a very robust and in most circumstances fairly forgiving in its binding when fused to other proteins. Also, thanks to the inert properties of biotin the adherence to or impregnation of the filament can be accomplished in quite harsh environments, without damaging any structures.</p> |

| − | <p><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/ | + | |

| − | + | <p>There are three straight-forward approaches to biologically publicizing the biotin on the PLA filament:</p> | |

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li> <strong>Method 1</strong>: Biotin can be actively linked to the filament or final structures</li> | ||

| + | <li> <strong>Method 2</strong>: Biotin can be impregnated in PLA, from which filament can be created for 3D printing</li> | ||

| + | <li> <strong>Method 3</strong>: Biotin can be coated on the filament or final structures</li> | ||

| + | </ul><br> | ||

| + | <p>Since the first option is generally far to expensive to make bulk quantities of biotin-activated PLA (Salem <i>et al.</i>, 2001; Ben-Shabat <i>et al.</i>, 2006; Weiss <i>et al.</i>, 2007), only option 2 and 3 were assessed in this work package.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <h2>Impregnation of PLA with biotin </h2> | ||

| + | <p>In this first approach, we tried to impregnate the biotin in the PLA. Therefore, we looked for a chemical condition in which a vast amount of PLA and biotin could be dissolved without changing or destroying their integrity. This condition was obtained by heating biotin-saturated dimethylformamide (DMF) to 130°C and dissolving PLA in it.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/d/d4/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament2.png" alt="fig2" height="599" width="449"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 2: Experimental setup for the impregnation of biotin</i></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>After thoroughly mixing the dissolved PLA and biotin, the PLA (with biotin) can be crashed out of solution by adding the solution to an excess of ethanol, saturated with biotin at room-temperature.</p> | ||

| + | <div class="center"><video controls="" style="width: 500px; height:auto;object-fit: contain;"> | ||

| + | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/c/ca/T--Ugent_Belgium--filamentmovie.mp4" > | ||

| + | </video></div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>In this way we obtained biotin that is completely captured by PLA in a nicely dispersed fashion. Moreover, it’s most likely that the biotin will remain in position and interwoven in the PLA fibers, even in circumstances of fog, dew, water,...</p> | ||

| + | <p>Next, the obtained crashed out and dried PLA can be supplied to an extruder that will generate a filament which can subsequently be used as feed for a 3D printer.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="row center"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6 center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/38/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament3.png" alt="fig3" height="491" width="491"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-6 center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/0/01/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament4.png" alt="fig4" height="491" width="491"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 3: left the set-up for the extruder and right the final generated filament</i></p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | + | <h2>Coating of PLA with biotin </h2> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>In this second approach, we made some kind of biotin-lacquer which can be painted on the filament and even on already printed structures. |

| − | + | This lacquer was created by over-saturating a solvent with PLA and biotin, that classically dissolves PLA. After a simple trial and error essay, dichloromethane was selected as the optimal solvent, due to its fast working method of action and easy preparation. </p> | |

| − | < | + | <div class="center"> |

| − | <p>< | + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/f/fb/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament5.jpg" alt="fig5" height="339" width="211"></p> |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 4: By simply submerging a PLA fragment in this solution, a biotin-PLA coating will be applied to the surface of the filament</i></p> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | </ | + | |

| + | <h2> Biological availability </h2> | ||

| + | <p>An important step is to test wether our filament shows biological activation after either impreganation or coating of biotin, by comparing it with uncoated PLA.</p> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/f/f7/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament6.png" alt="fig6" height="207" width="361"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 5: From left to right: PLA coated with biotin (method 3), PLA impregnated with biotin (method 2) and untreated PLA filament</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>In order to determine the biological activity of biotin on a solid carrier, a protocol was used based on the biological displacement reaction between the accessible biotin on the structure, and a HABA (4'-hydroxyazobenzene-2-carboxylic acid) solution, as described by Li, <i>et al.</i> (2007). | ||

| + | When the HABA is stoichiometrically displaced by biotin in the streptavidin-binding, a change in absorption is observed at 500nm wavelength, which provides the basis for a spectrophotometrical determination of accessible biotin levels (Fig. 6).</p> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/7/72/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament7.jpg" alt="fig7" height="257" width="352"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 6: Principle for determination of biologically available biotin on and in a PLA fiber. Adapted from Li et al. (2007).</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>In a first step, a concentration array needs to be made to ascertain the concentration of biologically available biotin in a standard solution. The concentration we get from the absorbance measurement is compared to the amount of biotin that is in the standard solution (after weighing and making the solution, fig. 7). | ||

| + | For every increment of volume (10µl of standard solution), the absorbance is measured and the concentration of biotin is determined using equation 1.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/f/f0/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament8.gif" alt="fig8" height="35" width="162"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Equation 1: Determination of Biotin concentration of a solution based on an absorbance measurement.</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>In order to determine the availability of biotin on the fibers itself, the HABA-streptavidin solution was prepared and pre-washed and pre-weighed pieces of PLA were iteratively added, vortexed for 1 minute and removed again. The resulting solution was measured every time at 500nm in a spectrophotometer. The color change is displayed in figure 8. After collecting the data, the amount of available biotin was calculated by using equation 2.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/7/7e/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament9.gif" alt="fig9" height="36" width="302"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Equation 2: Calculating the amount of available biotin base on an absorbance measurement.</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/34/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament10.gif" alt="fig10" height="437" width="800"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 7: Plot of the theoretical amount of biotin in solution, versus the amount that's calculated based on the HABA-streptavidin assay.</i></p> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/a/ab/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament11.png" alt="fig11" height="181" width="800"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 8: Picture of the end results of the HABA-streptavidin test with, from left to right, a positive control (solution with excess biotin), the final cuvette of the concentration range of the PLA-biotin made with method 2, the final cuvette from method 3, the final cuvette of the concentration range of the untreated PLA and a negative control (nothing added).</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <p>After calculating the amounts of available biotin, the results were compared to each other (Fig. 9). This shows that the two filaments that were activated show a similar amount of biologically available biotin. The untreated PLA shows almost no change in absorbance. </p> | ||

| + | <div class="center"> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8b/T--Ugent_Belgium--filament12.png" alt="fig12" height="434" width="752"></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <p class="center"><i>Figure 9: measured amount of biologically available biotin per gram PLA for, from left to right: method 3, method 2 and untreated PLA</i></p> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <h3 class="bottom">References</h3> | ||

| + | <ol> | ||

| + | <li>Ben‐Shabat, S., Kumar, N., & Domb, A. J. (2006). PEG‐PLA Block Copolymer as Potential Drug Carrier: Preparation and Characterization. <i>Macromolecular bioscience</i>, 6(12), 1019-1025. </li> | ||

| + | <li>Li, D., Frey, M. W., Vynias, D., & Baeumner, A. J. (2007). Availability of biotin incorporated in electrospun PLA fibers for streptavidin binding. <i>Polymer</i>, 48(21), 6340-6347.</li> | ||

| + | <li>Salem, A. K., Cannizzaro, S. M., Davies, M. C., Tendler, S. J. B., Roberts, C. J., Williams, P. M., & Shakesheff, K. M. (2001). Synthesis and characterisation of a degradable poly (lactic acid)-poly (ethylene glycol) copolymer with biotinylated end groups.<i>Biomacromolecules</i>, 2(2), 575-580. </li> | ||

| + | <li>Weiss, B., Schneider, M., Muys, L., Taetz, S., Neumann, D., Schaefer, U. F., & Lehr, C. M. (2007). Coupling of biotin-(poly (ethylene glycol)) amine to poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for versatile surface modification. <i>Bioconjugate chemistry</i>, 18(4), 1087-1094. </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </ol> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

{{Team:UGent_Belgium/footer}} | {{Team:UGent_Belgium/footer}} | ||

Latest revision as of 22:35, 19 October 2016

Filament

Overview

In the filament work package, we tried to produce a plastic filament that’s activated and susceptible to biological appendages. The filament can subsequently be used for printing the desired 3D structure. PLA (polylactic acid) was chosen as basic plastic carrier because of its biodegradability, optimal melting temperature, and general easy-to-print characteristics. In order to enhance the function of the PLA, i.e. improve the condensation capacity, we needed to attach biological nucleation proteins to the filament. In order to get the proteins attached to the final structure, either purified or expressed on the membrane of whole cells, a moiety needs to be present in order for the filament to capture them, bind them and keep them there (even while rinsing, or in flooded conditions).

General overview; 3D printed structure that's activated with biotin, will be succeptible for adhesion of proteins via biotin-avidin complexation

We chose to assess the biotin-(strept)avidin complex, since it’s a very robust and in most circumstances fairly forgiving in its binding when fused to other proteins. Also, thanks to the inert properties of biotin the adherence to or impregnation of the filament can be accomplished in quite harsh environments, without damaging any structures.

There are three straight-forward approaches to biologically publicizing the biotin on the PLA filament:

- Method 1: Biotin can be actively linked to the filament or final structures

- Method 2: Biotin can be impregnated in PLA, from which filament can be created for 3D printing

- Method 3: Biotin can be coated on the filament or final structures

Since the first option is generally far to expensive to make bulk quantities of biotin-activated PLA (Salem et al., 2001; Ben-Shabat et al., 2006; Weiss et al., 2007), only option 2 and 3 were assessed in this work package.

Impregnation of PLA with biotin

In this first approach, we tried to impregnate the biotin in the PLA. Therefore, we looked for a chemical condition in which a vast amount of PLA and biotin could be dissolved without changing or destroying their integrity. This condition was obtained by heating biotin-saturated dimethylformamide (DMF) to 130°C and dissolving PLA in it.

Figure 2: Experimental setup for the impregnation of biotin

After thoroughly mixing the dissolved PLA and biotin, the PLA (with biotin) can be crashed out of solution by adding the solution to an excess of ethanol, saturated with biotin at room-temperature.

In this way we obtained biotin that is completely captured by PLA in a nicely dispersed fashion. Moreover, it’s most likely that the biotin will remain in position and interwoven in the PLA fibers, even in circumstances of fog, dew, water,...

Next, the obtained crashed out and dried PLA can be supplied to an extruder that will generate a filament which can subsequently be used as feed for a 3D printer.

Figure 3: left the set-up for the extruder and right the final generated filament

Coating of PLA with biotin

In this second approach, we made some kind of biotin-lacquer which can be painted on the filament and even on already printed structures. This lacquer was created by over-saturating a solvent with PLA and biotin, that classically dissolves PLA. After a simple trial and error essay, dichloromethane was selected as the optimal solvent, due to its fast working method of action and easy preparation.

Figure 4: By simply submerging a PLA fragment in this solution, a biotin-PLA coating will be applied to the surface of the filament

Biological availability

An important step is to test wether our filament shows biological activation after either impreganation or coating of biotin, by comparing it with uncoated PLA.

Figure 5: From left to right: PLA coated with biotin (method 3), PLA impregnated with biotin (method 2) and untreated PLA filament

In order to determine the biological activity of biotin on a solid carrier, a protocol was used based on the biological displacement reaction between the accessible biotin on the structure, and a HABA (4'-hydroxyazobenzene-2-carboxylic acid) solution, as described by Li, et al. (2007). When the HABA is stoichiometrically displaced by biotin in the streptavidin-binding, a change in absorption is observed at 500nm wavelength, which provides the basis for a spectrophotometrical determination of accessible biotin levels (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Principle for determination of biologically available biotin on and in a PLA fiber. Adapted from Li et al. (2007).

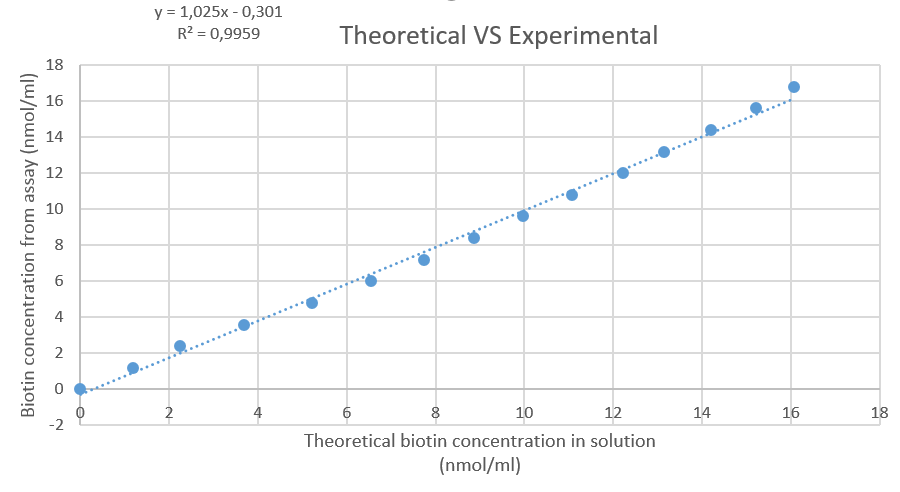

In a first step, a concentration array needs to be made to ascertain the concentration of biologically available biotin in a standard solution. The concentration we get from the absorbance measurement is compared to the amount of biotin that is in the standard solution (after weighing and making the solution, fig. 7). For every increment of volume (10µl of standard solution), the absorbance is measured and the concentration of biotin is determined using equation 1.

![]()

Equation 1: Determination of Biotin concentration of a solution based on an absorbance measurement.

In order to determine the availability of biotin on the fibers itself, the HABA-streptavidin solution was prepared and pre-washed and pre-weighed pieces of PLA were iteratively added, vortexed for 1 minute and removed again. The resulting solution was measured every time at 500nm in a spectrophotometer. The color change is displayed in figure 8. After collecting the data, the amount of available biotin was calculated by using equation 2.

![]()

Equation 2: Calculating the amount of available biotin base on an absorbance measurement.

Figure 7: Plot of the theoretical amount of biotin in solution, versus the amount that's calculated based on the HABA-streptavidin assay.

Figure 8: Picture of the end results of the HABA-streptavidin test with, from left to right, a positive control (solution with excess biotin), the final cuvette of the concentration range of the PLA-biotin made with method 2, the final cuvette from method 3, the final cuvette of the concentration range of the untreated PLA and a negative control (nothing added).

After calculating the amounts of available biotin, the results were compared to each other (Fig. 9). This shows that the two filaments that were activated show a similar amount of biologically available biotin. The untreated PLA shows almost no change in absorbance.

Figure 9: measured amount of biologically available biotin per gram PLA for, from left to right: method 3, method 2 and untreated PLA

References

- Ben‐Shabat, S., Kumar, N., & Domb, A. J. (2006). PEG‐PLA Block Copolymer as Potential Drug Carrier: Preparation and Characterization. Macromolecular bioscience, 6(12), 1019-1025.

- Li, D., Frey, M. W., Vynias, D., & Baeumner, A. J. (2007). Availability of biotin incorporated in electrospun PLA fibers for streptavidin binding. Polymer, 48(21), 6340-6347.

- Salem, A. K., Cannizzaro, S. M., Davies, M. C., Tendler, S. J. B., Roberts, C. J., Williams, P. M., & Shakesheff, K. M. (2001). Synthesis and characterisation of a degradable poly (lactic acid)-poly (ethylene glycol) copolymer with biotinylated end groups.Biomacromolecules, 2(2), 575-580.

- Weiss, B., Schneider, M., Muys, L., Taetz, S., Neumann, D., Schaefer, U. F., & Lehr, C. M. (2007). Coupling of biotin-(poly (ethylene glycol)) amine to poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles for versatile surface modification. Bioconjugate chemistry, 18(4), 1087-1094.