KasiaKozdon (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

| − | <br><h4>The biosynthetic locus was engineered by our team in a form allowing for high-yield and fine-tuned expression of mutacin III. We placed a strong T7 promoter upstream of mutA to obtain high levels of the propeptide, a repressible pTet promoter upstream of the mutBCDP co-transcription unit and an inducible araBAD promoter for the mutT gene, coding for the ATP-binding-cassette-like transporter of mutacin III. All illegal restriction sites were removed from the endogenous sequences by silent mutagenesis. </h4><br> | + | <br><h4>The <a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K239001">biosynthetic locus</a> was engineered by our team in a form allowing for high-yield and fine-tuned expression of mutacin III. We placed a strong T7 promoter upstream of mutA to obtain high levels of the propeptide, a repressible pTet promoter upstream of the mutBCDP co-transcription unit and an inducible araBAD promoter for the mutT gene, coding for the ATP-binding-cassette-like transporter of mutacin III. All illegal restriction sites were removed from the endogenous sequences by silent mutagenesis. </h4><br> |

<center> <img src = "https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/0/07/T--UCL--bacteriocindevice.png" > </center> | <center> <img src = "https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/0/07/T--UCL--bacteriocindevice.png" > </center> | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

| Line 142: | Line 140: | ||

<p> <center> Fig. 4. Green light-inducible device concept diagram. </center> </p> | <p> <center> Fig. 4. Green light-inducible device concept diagram. </center> </p> | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <h4> Our Dental BioBricks:</h4> | ||

| + | <h4><a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1954000">LanA - BBa_K1954000</a> </h4> | ||

| + | <h4><a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1954000">LanA - BBa_K1954000</a> </h4> | ||

| + | <h4><a href="http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K239009">GFP test devise for Spy promoter - BBa_K239009</a> </h4> | ||

Revision as of 01:12, 20 October 2016

<!DOCTYPE html>

HEALTHY TEETH, HEALTHY AGEING

Explore how we are re-designing the oral microbiome

to prevent tooth decay

to prevent tooth decay

Healthy heart, healthy ageing

See how we are re-designing the gut microbiome to reduce blood pressure as way of reducing the chance of age-related complications with the heart.

WHY TEETH?

The deterioration of oral health in the elderly is accompanied by an increased prevalence of caries and periodontal disease which are risk factors for some systemic diseases and nutrition problems (1), whereas the status of dental hygiene has been recognized as an important determinant of psychological well-being and its aggravation has been associated with an elevated incidence of depressive symptoms (2). In our project, we designed a biosynthetic device to serve as an alternative in preventative dental care for the elderly.

The problem: Biofilm formation and cariogenesis

The oral cavity is inhabited by a wide range of interacting communities of metabolically and structurally organized microorganisms which synthesize an extracellular polysaccharide matrix (EPS) enabling them to adhere to the surface of the teeth and assemble in matrix-embedded biofilms. Progressing biofilm accumulation puts the bacteria under increasing metabolic stress which leads to localized metabolite and acid accumulation and a shift in the dynamic homeostasis towards acid-tolerating species such as Gram-positive Streptococcus mutans (3). A resultant decrease in pH causes tooth demineralization and constitutes a mechanism of dental caries.

Our approach: a bacteriocin producing device

A decrease in biofilm formation caused by interference with the viability of certain bacterial species presents an approach towards limiting cariogenesis. Our team designed a locus capable of producing and exporting a mature form of an antimicrobial peptide known as mutacin III, first identified in Streptococcus mutans UA787 isolated from a caries-active white female patient in the late 1980s (4). Mutacin III is effective against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria implicated in dental caries, e.g. other strains of Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces naeslundii, while Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to inhibition (5).

The biosynthetic locus was engineered by our team in a form allowing for high-yield and fine-tuned expression of mutacin III. We placed a strong T7 promoter upstream of mutA to obtain high levels of the propeptide, a repressible pTet promoter upstream of the mutBCDP co-transcription unit and an inducible araBAD promoter for the mutT gene, coding for the ATP-binding-cassette-like transporter of mutacin III. All illegal restriction sites were removed from the endogenous sequences by silent mutagenesis.

Mutacin III is a ribosomally synthesized 22 amino acid screw-shaped lanthionine-containing peptide. The biosynthesis of mutacin III involves the expression of the structural gene mutA to make a prepropeptide, comprising a C-terminal propeptide and an N-terminal leader peptide from which the former undergoes processing and the latter is cleaved off before export into the medium (4). The specific post-translational modifications make mutacin III distinct from other bacteriocins and are introduced by enzymes coded for by other genes in the locus (mutBCDP).

Based on sequence homologies of genes in the locus with those of other lantibiotic biosynthetic loci it can be inferred that these enzymes catalyze the dehydration (mutB) and cyclization (mutC) of the propeptide serine and threonine residues which can condense with a neighboring cysteine residue (6) leading to the formation of lanthionine or methyllanthionine (thioether) bridges, respectively. The enzyme coded by mutD catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of the C-terminal cysteine residue (7) while the product of mutP is a serine protease which cleaves the leader peptide and is likely the last step in the biosynthesis (8).

The mature mutacin III is composed of rings connected by flexible linkers (Fig. 2) which may be important in the mechanism of bacteriocidal activity (9). Following export, the peptide is believed to form transmembrane pores as monomer aggregates leading to membrane disruption and efflux of cellular components (10). The content of anionic phospholipids in the membrane has been suggested to be an important factor influencing initial binding – mutacin III has a net positive charge whereas Gram-positive bacteria have a high relative amount of anionic lipids (11).

In one investigation of the activity of mutacin-related lantibiotic gallidermin it became clear that lantibiotics are more effective in preventing biofilm formation rather than in exterminating microorganisms already embedded in biofilms (12). To reflect this, our device could be used to transform E. coli cells and employed as an anti-cariogenic strategy in replacement therapy (Fig. 3). Such a novel bacterial strain would demonstrate features of a successful effector strain as it would not cause disease by itself and because it could displace the host pathogenic bacteria.

Importantly, there are very few existing examples of lantibiotic resistance compared with antibiotics and only one mechanism of resistance to mutacin III, known as CprRK in Clostridium difficile, has been established (13). Moreover, the fact that a closely related lantibiotic nisin has been shown to exhibit low in vivo toxicity levels (14) and has been widely used as food preservative from as early as mid 1940s (15) further encourages the prospect of considering the employment of mutacin III as an anti-cariogenic agent.

LanA

In addition to the proposed device, we created a separate Registry entry for lanA recognized as synonymous (identical in sequence) to mutA (4). It is a structural gene for mutacin 1140 identified in Streptococcus mutans JH1140. LanA is a propeptide gene which could be used as the first step towards the assembly of an alternative bacteriocin-producing device.

GFP Test Device for Spy Promoter

The oral cavity is inhabited by a wide range of interacting communities of metabolically and structurally organized microorganisms which synthesize an extracellular polysaccharide matrix (EPS) enabling them to adhere to the surface of the teeth and assemble in matrix-embedded biofilms. Progressing biofilm accumulation puts the bacteria under increasing metabolic stress which leads to localized metabolite and acid accumulation and a shift in the dynamic homeostasis towards acid-tolerating species such as Gram-positive Streptococcus mutans (3). A resultant decrease in pH causes tooth demineralization and constitutes a mechanism of dental caries.

We decided to target pH and an indicator of deteriorating oral health and use it as an system to regulate the relate of antimicrobial peptide known as mutacin III, is effective against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria implicated in dental caries, e.g. other strains of Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces naeslundii, while Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to inhibition (5).

An existing BioBrick in the iGEM registry (BBa_K239001), designed to detect misfolding of proteins in the periplasm or shear stress has been further characterised to demonstrate the BioBrick functions as a pH inverter.

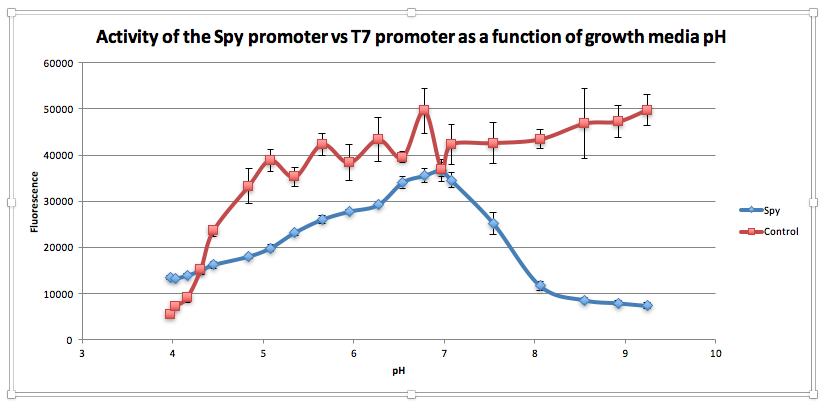

Compared to the control, as pH increases from 3.97 to 6.78, GFP expression gradually increases for E. coliwith BBa_K239009. The maximum GFP expression is observed at 6.78. GFP expression increases from 13,556.25 at pH 3.97 to 35,569 at pH 6.78. Beyond this maximum, there is a sharp decline in GFP expression as the starting LB broth increases in alkalinity, falling to 7,394 at pH 7,394. Conversely, for the control, a sharp increase is observed from pH 5393.5 at 3.97 to 38854.5 at pH 5.08. After this, the general trend is one of increasing fluorescence as pH increases, but the increase is more gradual.

From this experiment, we have established that BBa_K239009 (Spy Promoter) previously used to characterise protein misfolding can be used as a pH-sensitive promoter, as well. Thus, we have improved the function and characterization of an existing BioBrick Part.

Green light-inducible device

As a means of adding specificity of application to our existing devices, we designed a ‘template’ green light-inducible device (GLID) with blue output (amilGFP), adapted from Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. There are three components of the system: the chromatic acclimation sensor (CcaS), the response regulator (CcaR) and the PcpcG2 promoter. CcaS is a histidine kinase which is activated by green light and can catalyze phosphorylation of CcaR, leading to its activation and induction of gene expression downstream of PcpcG2. In our design (Fig. 4), there are two independently inducible promoters (Ptac and pBAD) allowing for fine tuning of gene expression by modifying the amount of IPTG and arabinose. This device contains an improvement of the existing part of the device (BBa_K592019) because it constitutes a self-contained functional system with an improved RBS for PcpcG2 adapted from (16), suspected to increase the level of expression of the genes downstream of the promoter by about 40 times compared to the wild-type promoter.

Our Dental BioBricks:

LanA - BBa_K1954000

LanA - BBa_K1954000

GFP test devise for Spy promoter - BBa_K239009

References

- Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello ALF, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–7.

- Rouxel P, Tsakos G, Chandola T, Watt RG. Oral Health-A Neglected Aspect of Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016 Mar 12.

- Anderson MH. Changing paradigms in caries management. Curr Opin Dent. 1992 Mar;2:157–62.

- Qi F, Chen P, Caufield PW. Purification of mutacin III from group III Streptococcus mutans UA787 and genetic analyses of mutacin III biosynthesis genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999 Sep;65(9):3880–7.

- Hillman JD, Johnson KP, Yaphe BI. Isolation of a Streptococcus mutans strain producing a novel bacteriocin. Infect Immun. 1984 Apr;44(1):141–4.

- Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Food Microbiology: Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005 Oct;3(10):777–88.

- Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacterial lantibiotics: strategies to improve therapeutic potential. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005 Feb;6(1):61–75.

- Sahl HG, Jack RW, Bierbaum G. Biosynthesis and biological activities of lantibiotics with unique post-translational modifications. Eur J Biochem. 1995 Jun 15;230(3):827–53.

- Moll GN, Roberts GC, Konings WN, Driessen AJ. Mechanism of lantibiotic-induced pore-formation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996 Feb;69(2):185–91

- Smith L, Zachariah C, Thirumoorthy R, Rocca J, Novák J, Hillman JD, et al. Structure and dynamics of the lantibiotic mutacin 1140. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2003 Sep 9;42(35):10372–84.

- Abee T. Pore-forming bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria and self-protection mechanisms of producer organisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995 Jun 1;129(1):1–9.

- Saising J, Dube L, Ziebandt A-K, Voravuthikunchai SP, Nega M, Gotz F. Activity of Gallidermin on Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Nov 1;56(11):5804–10.

- Draper LA, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Lantibiotic Resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2015 Jun;79(2):171–91.

- Hagiwara A, Imai N, Nakashima H, Toda Y, Kawabe M, Furukawa F, et al. A 90-day oral toxicity study of nisin A, an anti-microbial peptide derived from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, in F344 rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 Aug;48(8-9):2421–8.

- Delves-Broughton J. Nisin and its application as a food preservative. Int J Dairy Technol. 1990 Aug;43(3):73–6.

- Abe K, Miyake K, Nakamura M, Kojima K, Ferri S, Ikebukuro K, et al. Engineering of a green-light inducible gene expression system in S ynechocystis sp. PCC6803: Engineered green light gene expression system. Microb Biotechnol. 2014 Mar;7(2):177–83.