| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

<div style="height:100%"> | <div style="height:100%"> | ||

<section class="collabphoto parallax" style="text-align:center"> | <section class="collabphoto parallax" style="text-align:center"> | ||

| − | <h2 class="title"> | + | <h2 class="title" style="padding-top: 0;"> |

Community | Community | ||

</h2> | </h2> | ||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

<div class="block-wrapper-inner" style="padding-top: 15px;"> | <div class="block-wrapper-inner" style="padding-top: 15px;"> | ||

<div class="container" style="width: 75%; font-family: robotolight; color: #4d4d33"> | <div class="container" style="width: 75%; font-family: robotolight; color: #4d4d33"> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<h1 id="ZERO"> | <h1 id="ZERO"> | ||

| Line 142: | Line 143: | ||

<b> | <b> | ||

<u> | <u> | ||

| − | 1 | + | 1</u> |

| − | + | ||

</b> | </b> | ||

| − | + | part is on the registry’s list of well characterized parts. | |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | <p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | ||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

<p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | <p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | ||

| − | Having the | + | Having the mixed XbaI-SpeI restriction site resulting from the ligation of two biobricks directly upstream of the protein coding sequence would result in a T as the -3 base upstream of the start codon. It has been reported that in eukaryotic translation initiation, the -3 base is optimally an A or G (Kozak, 1996). This base is key in defining translation initiation, as changing it into a T or C increases sensitivity to differences in other bases upstream of the start codon. Cavener et al. (1991) on the other hand showed that yeast has a strong bias for A in this position. Because of this, protein-coding BioBricks would always require the direct fusion of a ribosome binding site upstream of the start codon in order for them to be usable within the context of the standard prefix and suffix. This, in turn, makes the use of non-BioBrick backbones difficult, as the promoters in these plasmids might already be suitable to clone a protein-coding sequence into them without any specific fusions. In addition, adaptation of <i>E. coli</i> biobricks for yeast, and variation in yeast ribosome binding sites, is made more difficult |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | <p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | ||

| − | Particularly with the DNA synthesis deal iGEM has had with IDT | + | Particularly with the DNA synthesis deal iGEM has had with IDT, and constantly lowering DNA synthesis costs, the importance of being able to obtain physical part copies from the registry is lower than ever before. For this reason, we find the requirements of the current assembly standard to be restrictive and limiting: assembling yeast biobricks with e.g. gBlock synthesis allows usage of the parts in much more suitable environments than the BioBricks context, which would require PCR modification. |

</p> | </p> | ||

<p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | <p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | ||

Ultimately, we believe that the most important function of the parts registry is the sharing of information about different parts and their function, and increasing understanding of parts’ interaction to facilitate the predictable engineering of biological systems. This purpose is no longer served when the delivery of physical part copies becomes a priority and limitation in itself. The current requirements set limitations that prevent progression in the field of synthetic biology, as teams are discouraged from pushing into uncharted territory. Our team sees great potential in the use of yeast as a chassis in future projects, but current iGEM criteria set limitations to the convenience of its use. | Ultimately, we believe that the most important function of the parts registry is the sharing of information about different parts and their function, and increasing understanding of parts’ interaction to facilitate the predictable engineering of biological systems. This purpose is no longer served when the delivery of physical part copies becomes a priority and limitation in itself. The current requirements set limitations that prevent progression in the field of synthetic biology, as teams are discouraged from pushing into uncharted territory. Our team sees great potential in the use of yeast as a chassis in future projects, but current iGEM criteria set limitations to the convenience of its use. | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | |||

<p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | <p class="justify" style="font-size:19px"> | ||

<b> | <b> | ||

| Line 181: | Line 184: | ||

, 44(2), pp. 283-292 | , 44(2), pp. 283-292 | ||

</p> | </p> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="block-wrapper-inner" style="padding-top: 15px;"> | <div class="block-wrapper-inner" style="padding-top: 15px;"> | ||

Latest revision as of 09:51, 3 December 2016

Community

Yeast as a Chassis in iGEM

As we noticed how many problems choosing yeast as a chassis can cause, we decided that bringing attention to these issues would be a valuable contribution to the iGEM community. Yeast, being an eukaryote, offers many advantages compared to prokaryotic chassis options such as E. coli. Using an eukaryotic chassis makes it possible to execute projects that could not be carried out with prokaryotic organisms, and allows to expand the scope of topics covered by iGEM projects.

The first obstacle to be encountered when considering yeast as a chassis is the availability of parts in the registry. We made an inventory of parts available for yeast in the registry, and compiled the following statistics:

Out of more than 20,000 BioBricks, 163 are designed for yeast.

Out of these, 31 are available.

Out of these, 1 part is on the registry’s list of well characterized parts.

Because of this, any team that uses yeast as a chassis is pushed to use vectors and parts outside of the registry, which might not comply with the limits the BioBrick RFC 10 assembly standard sets. This creates a major hindrance to the creation of yeast parts, as iGEM guidelines and medal criteria require submission in the standard BioBrick backbone, with parts being flanked by the standard BioBrick prefix and suffix.

This, in turn, means a considerable amount of additional work to fulfill iGEM criteria and modify parts to be shipped in the standard backbone. Such a thought might discourage teams from pursuing ideas they have for yeast-related projects. In addition, doing these modifications doesn’t seem very motivating, as the framework offered by the conventional assembly standard offers a poor environment for the function of yeast BioBricks.

Having the mixed XbaI-SpeI restriction site resulting from the ligation of two biobricks directly upstream of the protein coding sequence would result in a T as the -3 base upstream of the start codon. It has been reported that in eukaryotic translation initiation, the -3 base is optimally an A or G (Kozak, 1996). This base is key in defining translation initiation, as changing it into a T or C increases sensitivity to differences in other bases upstream of the start codon. Cavener et al. (1991) on the other hand showed that yeast has a strong bias for A in this position. Because of this, protein-coding BioBricks would always require the direct fusion of a ribosome binding site upstream of the start codon in order for them to be usable within the context of the standard prefix and suffix. This, in turn, makes the use of non-BioBrick backbones difficult, as the promoters in these plasmids might already be suitable to clone a protein-coding sequence into them without any specific fusions. In addition, adaptation of E. coli biobricks for yeast, and variation in yeast ribosome binding sites, is made more difficult

Particularly with the DNA synthesis deal iGEM has had with IDT, and constantly lowering DNA synthesis costs, the importance of being able to obtain physical part copies from the registry is lower than ever before. For this reason, we find the requirements of the current assembly standard to be restrictive and limiting: assembling yeast biobricks with e.g. gBlock synthesis allows usage of the parts in much more suitable environments than the BioBricks context, which would require PCR modification.

Ultimately, we believe that the most important function of the parts registry is the sharing of information about different parts and their function, and increasing understanding of parts’ interaction to facilitate the predictable engineering of biological systems. This purpose is no longer served when the delivery of physical part copies becomes a priority and limitation in itself. The current requirements set limitations that prevent progression in the field of synthetic biology, as teams are discouraged from pushing into uncharted territory. Our team sees great potential in the use of yeast as a chassis in future projects, but current iGEM criteria set limitations to the convenience of its use.

References

Cavener, D.R., Ray, S.C, 1991, Eukaryotic start and stop translation sites. Nucleic Acids Research , 19(12), pp. 3185-3192

Kozak, M., 1996, Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell , 44(2), pp. 283-292

Conferences

We participated in two iGEM meetups – the Nordic iGEM Conference, or NiC, which was held in Stockholm, and The European Experience in Paris. They gave us a great opportunity to present our project, meet other iGEM teams, hear about their projects and collaborate. We got to socialize with other iGEM teams and see their approaches in tackling problems regarding all aspects of the project (e.g. fundraising, wet lab, research, etc.). All teams seemed to have had similar difficulties, so it was nice to know we weren’t alone. In the end we learned how iGEM projects are done in different countries, got acquainted with the cultures of Sweden and France, did sightseeing, experienced a Swedish Gasque and even paid a visit to aunt Mona Lisa!

At NiC, we got a chance to practice our project presentation skills by taking part in the Mini Jamboree. It was the first time we presented our project for an audience of that size, and we placed in the top 4. The winners, team Copenhagen, got the honor of hosting the NiC next year. In the two great workshops that followed, we got to ponder some questions on bioethics, and imagined what the world would look like in a future where everything is based on synthetic biology.

The judges, who were ex-iGEMers themselves, shared their experiences with us about the current state of biotechnology in Sweden. The conference overall had a very warm setting and thanks to it we made some good friends. One of these friendships later led to a collaboration, which we will present below.

The Paris conference gave us a chance to prepare our first poster and take part in a lively poster session with more than twenty teams from all over Europe. There was an interesting panel discussion about biosecurity and the challenges and risks in synthetic biology.

These conferences also gave us a chance to meet iGEM officials – Vinoo Selvarajah and Randy Rettberg who gave us good advice which we will take into account in selecting next year’s Aalto-Helsinki team. They advised us to “select your project and start as soon as possible so that you have enough time to get something done”.

“ Select your project and start as soon as possible so that you have enough time to get something done ”

Collaborations

We were lucky to have quite a few collaborations. We got to help in starting up a new iGEM team, as we were approached by the UCLouvain team from Belgium. It happened to be that one of their team members was on an exchange in the University of Helsinki, so we met and talked. We told as well as we could how our team was assembled the first time and what problems the first team had had. We talked about financing the project, choosing the project subject and about founding an organization to help with the financial side. Hopefully our tips were helpful and UCLouvain has had a great time in iGEM!

Thanks to the Stockholm conference we made good friends with the other Nordic iGEM teams and got to do a small collaboration with the Uppsala team. They asked for general information and methods for working with yeast, since they knew from our NiC presentation that our project involved S. cerevisiae . We had a Skype meeting with them and sent our protocols.

EPF Lausanne team contacted us regarding a collaboration project they were planning to do which was somewhat related to our CollabSeeker. They wanted to create a platform, in the form of a blog or website, on which they could present iGEM teams and projects through “news articles”. We informed them about the CollabSeeker, and their reaction was positive. We ended up giving them an interview via Skype, telling more about our search engine and answering questions to the survey they had prepared.

We also got in touch with a few other teams. We shared information about ourselves and CollabSeeker for XMU-China team’s exchange platform – Newsletter.

We had a Skype meeting with TEC CEM team and shared information about our teams as well as projects. The team, which is from Mexico, didn’t know that we had a true mexican in our team, and finding out about this was really fun for both teams.

We also helped METU HS Ankara team who wanted to create a database consisting of protocols in different language. We helped them to achieve their goal by translating our protocols into Finnish. The protocols were about Transformation, LB Broth, LB Agar, ONC, Competent Cell Preparation by Calcium Chloride, Getting the DNA Parts from the Kit Plate, Mini Prep Plasmid Isolation and Plasmid Isolation.

Founding an iGEM organization

As this was the third year Aalto-Helsinki competed in iGEM, we decided that it was time to strengthen the continuity of the team and also provide basis for an Aalto-Helsinki community. This is why we founded an organization called Aalto-Helsinki Synthetic Biology ry, for all the members of the previous years’ and the present year’s teams. An organization would provide a great channel for communicating with the old teams and also helped a lot with handling our finances.

As we were at the Nordic iGEM Conference, there was a lot of discussion of collaboration between different teams’ iGEM organizations. The discussions even led to the idea of a Nordic iGEM organization, which would function as a community for all the nordic iGEM organizations. However, as we had just founded the Aalto-Helsinki Synthetic Biology ry and wanted to get that running smoothly first, in addition to having to focus on our iGEM project, nothing concrete was decided yet. The discussion of possible collaboration will probably start again after the Jamboree.

“ We decided that it was time to strengthen the continuity of the team and also provide basis for an Aalto-Helsinki community ”

Software

The CollabSeeker

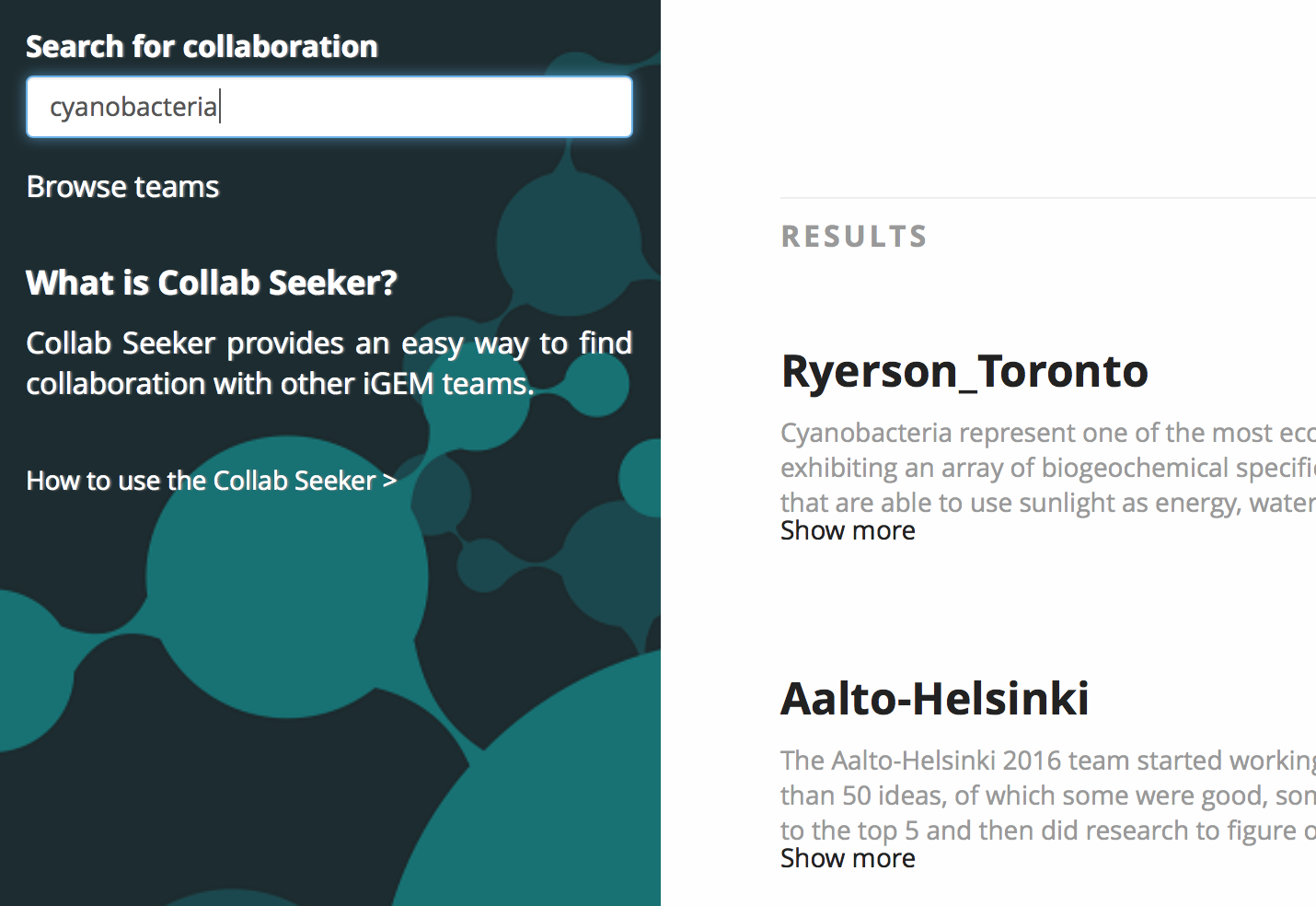

CollabSeeker is a collaboration search tool for the iGEM community, available at collab.aaltohelsinki.com . It is intended to help iGEM teams easily find the contact details and project information of other teams for collaboration purposes.

The original version of the CollabSeeker was made by the last year’s Aalto-Helsinki team. It was based on the idea of teams writing their project and contact information into the system, with CollabSeeker essentially functioning as a communication platform. Other similar platforms are available, such as the iGEM Matchmaker and the iGEM Match website of the UC Davis team.

None of the available platforms have been very popular, however. The main problem is that these sorts of platforms only produce value once a large user base already exists, but a large user base can only form once the platform produces enough value to attract new potential users. In order to fix this problem, we knew we had to come up with a way to produce value and attract users without having an existing user base to back us up.

Enter CollabSeeker 2.0! This time around, we would not require teams to fill in their information for us. Instead, we would mine igem.org, Facebook and Twitter for the project descriptions and Facebook and Twiter pages of all the iGEM teams around the globe. Of course it would be pure insanity to try to do this manually, so we created a suite of small, automated software tools for the purpose.

We hope that the whole iGEM community will embrace the CollabSeeker, and that in the years to come it will become a mundane part of the project that everyone will use in a similar manner as Aalto-Helsinki’s BioBrick and Team Seekers.

How to use the CollabSeeker

The CollabSeeker search engine can be used without logging in. However, every team has a team page which can be edited only by the team in question, and this requires login. The iGEM teams are able to log in using Facebook, Twitter or login credentials provided by the Aalto-Helsinki team.

The team descriptions and links to Facebook and Twitter accounts have been automatically uploaded on every team’s team page. The teams are able to modify their project descriptions, specify their collaboration desires and add contact information.

To easily find collaboration partners we added the opportunity to add collaboration categories to the team pages. All the collaboration categories can be found on the front page of the CollabSeeker.

Searching for teams based on their team names and team description is possible by using the search bar. The user has also the option to browse through all the teams available on CollabSeeker.

How we did it

In order to implement more advanced functionality in the CollabSeeker, we rewrote the engine entirely in Java using the Spring MVC framework and the Thymeleaf templating engine. In the process, the old html templates had to be heavily modified as well, so even though we preserved the looks of last year’s version, under the hood everything has changed.

The search engine is implemented using the popular Apache Lucene search framework, which was chosen due to it’s support of boolean search operators. In addition, we implemented both Facebook and Twitter login using Spring Social. However, our implementation of Facebook login requires the manage_pages permission, which we repeatedly requested from Facebook without luck, and therefore the feature had to be scrapped at the last minute. Twitter login is fully functional.

As mentioned, the basic architecture of CollabSeeker is based around the Model-View-Controller or MVC design pattern.

The CollabSeeker database is based around a single repository storing the information for each team. Under the hood, the database is implemented with PostgreSQL, but the Spring Framework provides an abstracted interface requiring no proficiency with SQL.

In order to link the team repository to searchable project details, all project information is stored within ASCII-encoded text files that are indexed by the Apache Lucene indexer. Each file is named after the team that it contains the project details of. When the user searches for terms, say “cyanobacteria” and “microcystin”, the Apache search engine uses the index to find a corresponding file and returns its name. The name is then linked to a team in the team repository using the findByName() method, and a view containing a listing of the applicable teams is constructed and shown to the user.

The Facebook and Twitter login features are based on the Spring Social and Spring Security plugins. Spring Security essentially takes care of all the needed authentication, while Spring Social is used only to connect a facebook or twitter profile to the correct team, after which Spring Security takes over the login process. The normal login using Aalto-Helsinki -provided credentials runs entirely through Spring Security. The passwords we provide are cryptographically secure random strings produced by the SecureRandom Java class. It is nonetheless suggested that users change their passwords once they have logged in with credentials we have provided.

The front-end is based on the Thymeleaf templating engine. Additionally, we use Javascript to produce certain functions such as “show more..” -links for long project descriptions.

As stated, we have created a suite of tools in the Ruby programming language for automatically finding iGEM teams’ contact details on Facebook and Twitter as well as their project information on the iGEM website.

The source code for the CollabSeeker is available under the MIT license on Github .

WikiFire+

The WikiFire+ is a new, Python-based tool for automatic fast uploading of iGEM wikis to the servers. It is based on the Aalto-Helsinki 2014 team’s Quickifier, but is again vastly improved in terms of functionality and implementation.

The current version of WikiFire+ not only automatically sends html files to the iGEM servers using the Python requests library, it also automatically checks for any css or javascript files these html files link to, automatically sending these to the servers as templates. It also automatically sends any images contained in the html to the servers, and fixes the links contained in the html to point to the correct pages. Essentially it allows iGEM wikis to be developed completely locally with a hassle-free, quick upload.

The WikiFire+ is implemented in python using particularly the requests library for sending data to the web, and the BeautifulSoup html parser for automatic sending of image, css and javascript files. The tool is available on GitHub under the MIT license.

“ We hope that the whole iGEM community will embrace the CollabSeeker, and that in the years to come it will become a mundane part of the project ”

InterLab study

Background

In order to compare results of similar experiments from different sources iGEM has proposed Interlab studies. It’s a set of experiments that teams can volunteer to do in order to deal with relative results issue. The aim is to improve the tools available to both the iGEM community and the synthetic biology community as a whole. This year’s goal was to let different teams measure fluorescence level of GFP protein. With minor difficulties we managed to complete the experiments and submit our results.

Overview

Work done in different labs can be hard to compare sometimes due to different measurement techniques or reporting methods. In order to address this issue iGEM has come up with Interlab studies which can be carried out by different teams around the world. Results of these studies are eventually combined to give understanding of relative issues arising during the process.

One of the big challenges in synthetic biology is that measurements of fluorescence usually cannot be compared because they are reported in different units or because different groups process data in different ways.Often one works around this by doing some sort of “relative expression” comparison; however, being unable to directly compare measurements makes it harder to debug engineered biological constructs, harder to effectively share constructs between labs, and harder even to just interpret your experimental controls.

This year iGEM had two protocols for measuring GFP fluorescence that would result in common, comparable units for teams to test out.

Results

Cell competency test

Before using our competent cells in our experiment, we had to use the Competent Cell Test Kit [1] provided by iGEM to test the efficiency of our competent cells. The kit included five vials of purified DNA from BBa_J04450 in plasmid backbone pSB1C3. Each vial contained DNA at a different concentration: 50pg/µl, 20pg/µl, 10pg/µl, 5pg/µl, 0.5pg/µ. Transformations had to be performed with each of these to determine how efficient our competent cells were.

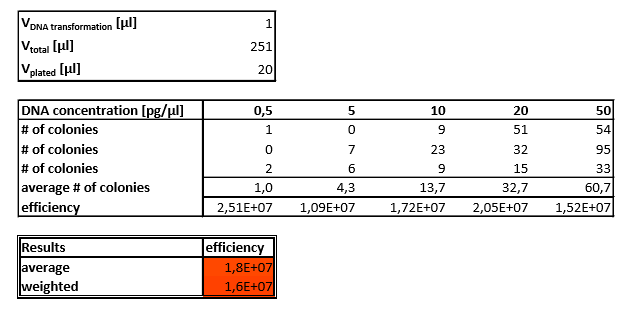

We used TOP10 Escherichia coli competent cells and SOC medium from the Gibson assembly kit that we ordered separately from New England Biolabs. On the first try we got around 10 colonies overall and clearly failed. Then we tried it again with one difference in the procedure - we added plasmids into the cells during the transformation, not the other way around which was written in the iGEM protocol. Unfortunately, it didn’t work the second time either and we got similar results. Not giving up, we tried it a third time and this time we additionally used pJR18 plasmid for positive control with three concentrations - 500 pg/µl, 50 pg/µl and 5 pg/µl. Also for the antibiotic we used ampicillin instead of chloramphenicol and this time it finally worked. Although after counting the colonies it was revealed that transformation efficiency was quite low - 1.8E7 cfu/µL on average and weighted 1.6E7 cfu/µL it was good enough to proceed with the transformations and start the actual experiments. Our competency results can be found in table 1.

Calibration protocols

1. OD600 Reference point

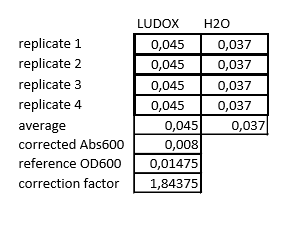

We accidentally put the LUDOX solution into -20 storage room so we had to order a new one. After it arrived we put it into wells with water according to the protocol [2] and measured it with a plate reader. After entering the numbers gotten from the plate reader into the excel sheet we got the final values - corrected Abs600, reference OD600 and correction factor (table 2).

2. Protocol FITC fluorescence standard curve

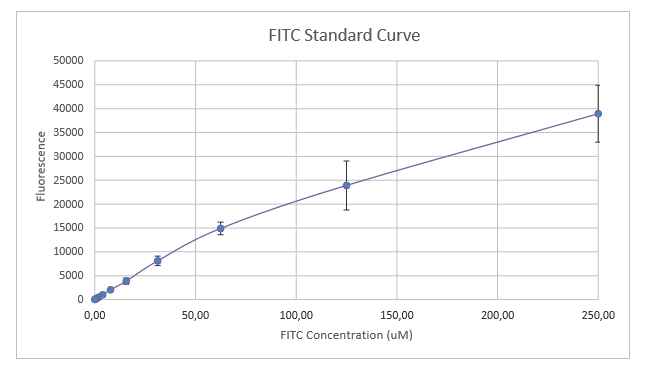

By following all the advice and procedures mentioned in the Calibration Protocol [2] we prepared 1xPBS, 2xFITC, incubated 2xFITC and prepared the 1xFITC solutions. Then having the solution, we did the serial dilutions according to the protocol and measured the fluorescence with a plate reader. After entering the numbers into the excel sheet we were able to calculate the standard curve of fluorescence for FITC concentration. Our results can be seen in figure 1.

Cell measurement protocol

Finally, after finishing all the calibrations, we did the transformations of five plasmids (three devices, positive and negative control). We succeeded only on our third time. The plasmids we received in the measurement kit [3] were dried out so we had to resuspend them in 100µLs of diH2O. Almost everything was done according to the transformation protocol [4] . Few differences were that after resuspending dried up DNA we were supposed to add 5µL it but we added 10µL. Then for the transformation of device 1 we did the heat shock for 70 seconds instead of 60. Also, we had to keep plates with colonies in the fridge for about three weeks due to some reasons. Therefore, we decided to do the restreaking of all colonies. Later these new colonies were used for cell cultures.

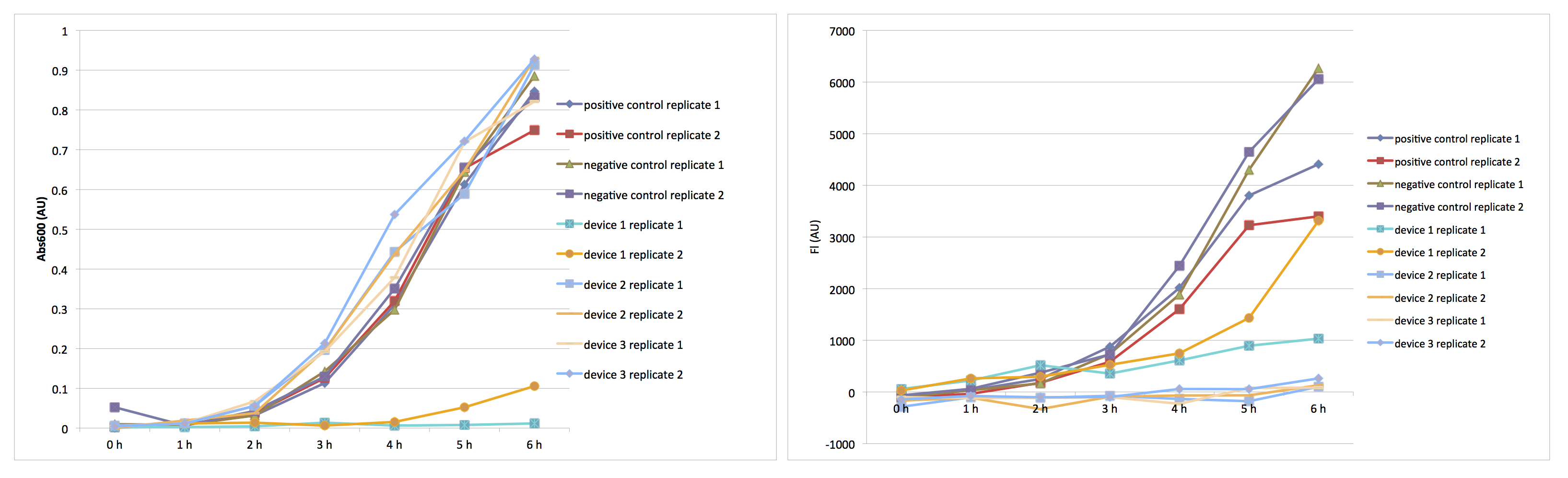

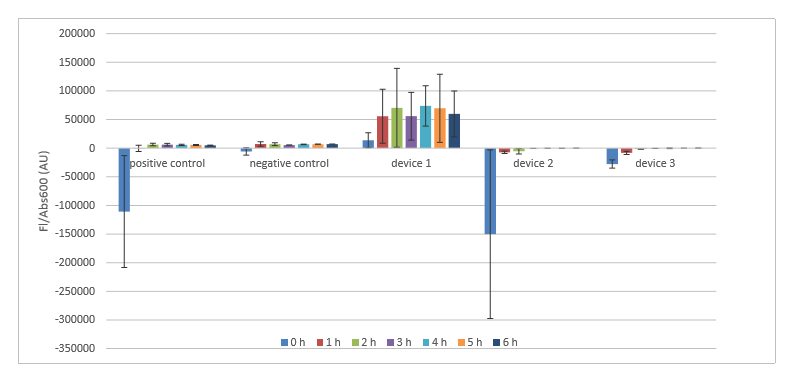

After growing of cell cultures was done we measured their OD600. Later, after diluting the cultures to a target OD600 of 0.02 and completing other necessary procedures we measured the hourly recording. Results can be found in figures 2 and 3.

Protocols and lab book

Links to protocols:

[1] Competent Cell Test Kit

[2] Plate Reader Protocol

[3] InterLab Measurement Kit

[4] Transformation Protocol

Link to our lab book: