(→semi stable transfection of our receptors in human cells) |

(→Results: Design of signal peptides and characterization) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

==Results: Design of signal peptides and characterization== | ==Results: Design of signal peptides and characterization== | ||

| − | [[File: | + | |

| + | [[File:Rsz receptor signalpeptideresults 002.png|thumb|center|850px| ClustalW multiple sequence alignment of a section containing the CMV promoter-signal peptide ORF junction, showing the consensus sequence, the degree of identity as well as the sequences of the signal CMV-signal peptide constructs for the IgKappa signal peptide, the BM40 signal peptide and the EGFR signal peptide. The respective sequences are annotated for their functional elements, including the CMV promoter, the TATA box, the RFC10 cloning scar, the Kozak consensus sequence and the respective beginning of the signal peptide ORFs. Gap open penalty is set to 15, gap extension penalty to 6.66. The program used for the alignment is Geneious 9.1.6.Results of the secretion luciferas assay. Shown are the relative intensities for the three signal peptides and a non-transfected negative control obtained via the luciferase assay immediately after transfection and after 12, 24, 36, 48, 60 and 72 hours. Error bars indicate the standard deviation as obtained via biological triplicates.]] | ||

For the quantification of signal peptide functionality via the first approach, constructs only containing the CMV promoter, one of three signal peptides - the EGFR signal peptide, the Igκ signal peptide or the BM40 signal peptide, a nanoluciferase, a Strep-tag II, and the hGH polyadenylation signal sequence were used. Lacking a transmembrane domain but containing a signal peptide, these constructs are being translocated into the ER and - not containing any further targeting signal - then secreted into the medium. Using the luciferase assay, one can quantifiy the amount of luminescence - and thus, proportionally, the amount of secreted nanoluciferase - by measuring the conversion of luciferin into visible light and integrating it over a certain timespan. | For the quantification of signal peptide functionality via the first approach, constructs only containing the CMV promoter, one of three signal peptides - the EGFR signal peptide, the Igκ signal peptide or the BM40 signal peptide, a nanoluciferase, a Strep-tag II, and the hGH polyadenylation signal sequence were used. Lacking a transmembrane domain but containing a signal peptide, these constructs are being translocated into the ER and - not containing any further targeting signal - then secreted into the medium. Using the luciferase assay, one can quantifiy the amount of luminescence - and thus, proportionally, the amount of secreted nanoluciferase - by measuring the conversion of luciferin into visible light and integrating it over a certain timespan. | ||

| − | + | ||

<br><br><br><br> | <br><br><br><br> | ||

<br><br><br><br> | <br><br><br><br> | ||

Revision as of 14:00, 16 October 2016

The receptors

While think before you ink is a popular slogan by tattoo adversaries, it has also been 100% applicable to creating our approach of bioprinting. Careful planning is, of course, necessary to create a construct that fulfills its role in the most functional way possible. In the following, we are going to explore the thought processes that went into the design of the receptors we built to mediate cross-linking of cells for bioprinting, as well as the design of other functional parts involved in our project.

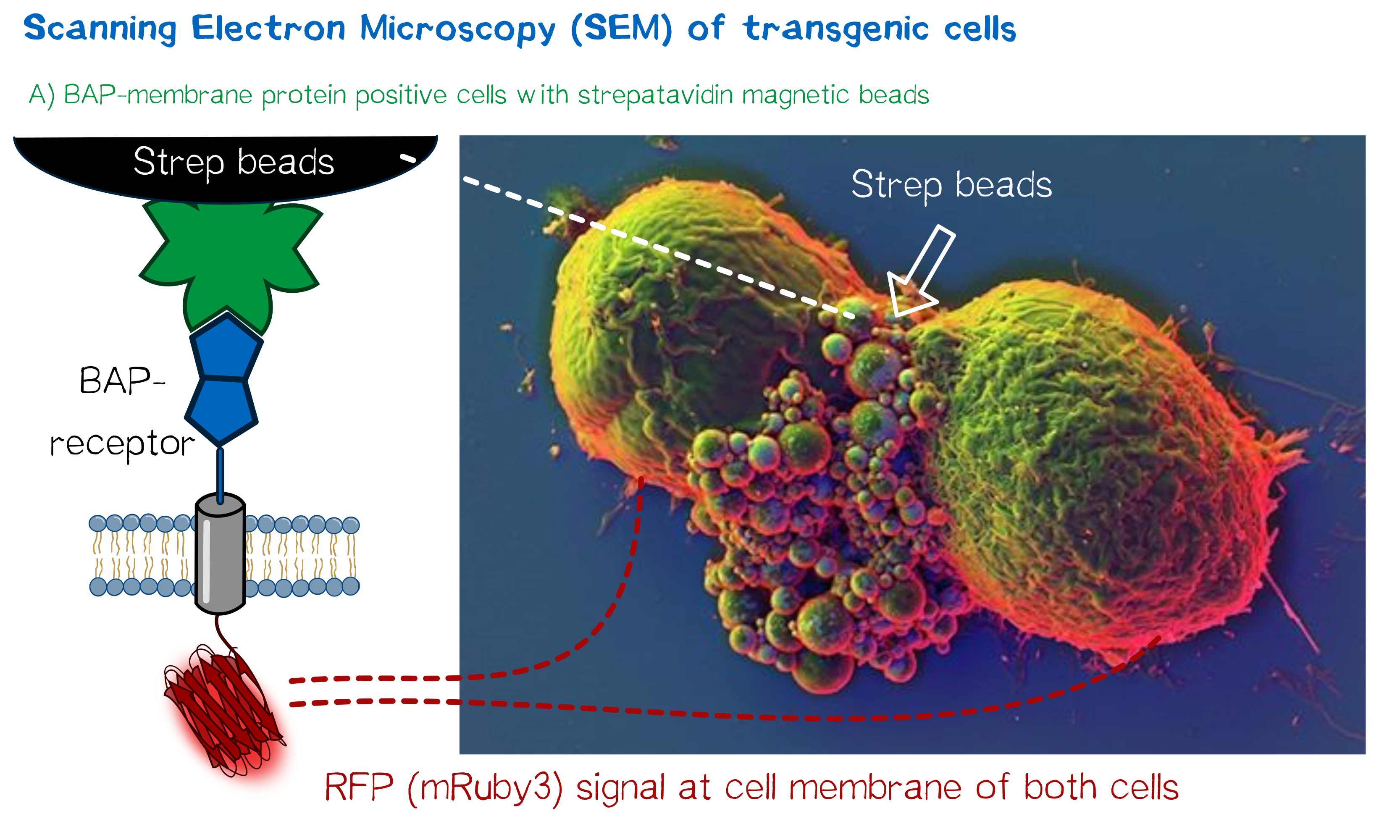

Therefore, we built two receptor constructs that both on their own, when being expressed in mammalian cells, are able to mediate interactions with streptavidin, allowing printing with subsequent polymerization of genetically engineered cells:

1) A receptor presenting an extracellular biotin acceptor peptide (BAP) that is endogenously biotinylated by a coexpressed biotin ligase (BirA).

The biotin acceptor peptide (BAP) is a short peptide sequence originating from E. coli. The sequence, being composed of 15 amino acid residues, is biotinylated specifically at a lysine residue within the recognition sequence by a coexpressed biotin ligase (BirA)[1] and can thus mediate the functionality of the receptor by allowing the interaction with streptavidin in the reservoir solution. The biotin ligase BirA is therefore encoded by the same vector as the receptor, with an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) allowing translation of two open reading frames (ORFs) from a single polycistronic plasmid. BirA is targeted to the ER via an Igκ signal peptide as well as an ER retention signal. Thus being permanently located in the ER, BirA is able to biotinylate the BAP of translocating proteins upon their translocation, i.e. to the cell surface.

2) Receptors presenting an extracellular, single-chain streptavidin variant.

These avidin derivates, by design, allow the functional fusion of the otherwise tetrameric avidin molecule with our receptor. Two different variants were hereby used: The so-called enhanced monomeric avidin is a single subunit avidin and able to bind biotin without tetramerization, and single-chain avidin, which resembles the form of the original avidin tetramer, but consists of only a single chain, with subunits being connected via polypeptide linkers.

Both receptors generally mediate the same purpose: By interacting with streptavidin in the printing reservoir - either directly (biotin acceptor-peptide) or indirectly via a biotinylated linker (single chain-avidin variants), cells are being cross-linked due to the polyvalent nature of the streptavidin molecules in solution.

The incredible journey: signal peptides and protein targeting

At the beginning of the 1970s, later Nobel Prize laureate Guenther Blobel made the discovery that some in vitro translated proteins would turn out slightly longer than their counterparts found in cells. This observation led to the discovery of the signal peptide, a short N-terminal protein sequence that is required for the targeting of proteins into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where it is cleaved off afterwards. This mainly hydrophobic sequence, being both required and sufficient for membrane proteins to be translocated to their place of action, allows targeting of proteins to the ER and to their specific location in the membrane - in the case of receptors to the cell surface. The signal peptide is a short peptide (less than 30 amino acids) that is recognized by the so-called signal recognition particle upon translation at the rough ER, which mediates the co-translational translocation of the protein’s peptide chains into the ER. During this project, three different peptides are being tested in order to determine the ideal one:

1) The EGFR signal peptide was taken from the iGEM parts registry (BBa_K157001) and combined with the CMV-promoter via the RFC10 cloning standard.

2) The BM40 and Igκ signal peptides were synthesized and combined with a BioBrick containing the CMV promoter () sequence via restriction cloning. As shown below, the EGFR signal peptide taken from the parts registry is constructed in a way that the signal peptide ORF immediately follows the RFC10 cloning scar after the CMV promoter, thus resulting in a very short 5’ untranslated region (UTR) of the transcribed mRNA. The combination of the CMV promoter with the synthesized BM40 and Igκ signal peptides allows for a considerably longer 5’ UTR of the resulting mRNA - additionally allowing them to contain a full Kozak consensus sequence by design. The Kozak sequence is recognized by the ribosome as a translational start site; this element missing or deviating from the consensus sequence may considerably decrease translation efficiency. For the EGFR signal peptide construct, a Kozak sequence is not present, as it would have to preceed the start codon ATG - a position which is occupied by the RFC10 cloning scar. Since both the distance from the promoter to the open reading frame as well as the Kozak consensus sequence are considered crucial parameters for expression levels[2], the BM40 and Igκ constructs were designed to potentially increase expression levels of the receptor.

Prediction of signal peptide functionality

As the quantitative functionality of signal peptides was not obvious from the beginning, the three options (Igκ, BM40, EGFR) were tested via bioinformatic tools as well as a secretion assay of luciferase constructs containing the respective peptides. Concerning the theoretical prediction of signal peptide efficiency, SignalP[3] is able to determine whether a sequence is likely to function as a signal peptide in general, as well as being able to predict the probable cleavage site of the signal peptide after its translocation into the ER. For all constructs, signal peptide functionality is predicted, as well as a potential cleavage site. The complete translated amino acid sequences of the respective receptor constructs were used as input. The algorithm for eukaryotes with default D-cutoff value was chosen.

For all three signal peptides, the high S-score indicates general signal peptide functionality. For the Igκ signal peptide, a cleavage site between amino acid 20 and 21 within the signal peptide is predicted. For the BM40 signal peptide, a cleavage site between amino acid 17 and 18 is predicted, and for the EGFR signal peptide, a cleavage site between amino acid 24 and 25 is predicted.

Results: Design of signal peptides and characterization

For the quantification of signal peptide functionality via the first approach, constructs only containing the CMV promoter, one of three signal peptides - the EGFR signal peptide, the Igκ signal peptide or the BM40 signal peptide, a nanoluciferase, a Strep-tag II, and the hGH polyadenylation signal sequence were used. Lacking a transmembrane domain but containing a signal peptide, these constructs are being translocated into the ER and - not containing any further targeting signal - then secreted into the medium. Using the luciferase assay, one can quantifiy the amount of luminescence - and thus, proportionally, the amount of secreted nanoluciferase - by measuring the conversion of luciferin into visible light and integrating it over a certain timespan.

Receptor elements: Targeting, stability and detection

Apart from their functional parts that mediate the (strept)avidin-biotin interaction, several other considerations were made. Other elements in the receptor were designed to make sure it is optimally translocated to the membrane, as stable as possible, and easily detectable.

For the receptor itself, it is of course of utmost importance that it is correctly anchored in the membrane, resulting in the correct localization of domains in either intercellular or extracellular space. For this purpose, a transmembrane domain of a type I membrane protein, the human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), was chosen and modified for maximum functionality. For correct trafficking of the receptor into the ER and, subsequently, its relocation on the cell surface, a properly functioning signal peptide had to be determined. More details on the decisions involved in protein targeting can be found in the corresponding section below.

Moreover, the receptor contains three functional elements for its detection: The intracellulary located red fluorescent protein mRuby 3 for detection of the receptor via fluorescence microscopy, an extracellular epitope domain for immunochemical detection via A3C5-antibody fragments and an intracellular Strep-tag II for the detection and purification via immunochemical methods.

The vector furthermore contains the poly-adenylation signal of human growth hormone (hGH) for functional polyadenylation of the transcribed mRNA. A description for the respective functional elements is given in the following sections.

EGFR transmembrane domain

For anchoring in the membrane, we decided to use a type I membrane protein. This type of membrane proteins possesses a single membrane span with defined localization of N-terminus out- and inside of the cell, respectively. The N-terminal transmembrane α-helix of human EGFR (UniProt P00533, amino acids 622-653) was chosen as the transmembrane domain of the receptor. A stop-transfer sequence consisting of charged amino acids - as it is characteristic for type I membrane proteins - was added at the C-terminus, and the sequence was furthermore flanked by a (GGGGC)2-linker at the N- and C-terminus, respectively. As predicted by the TMHMM 2.0 server for the prediction of transmembrane helices, amino acid residues N-terminal of the transmembrane domain are positioned outside of the cell, while residues C-terminal of the domain are positioned on the inside of the cell.

A3C5 epitope tag

Antibodies have various areas of application in life science, including protein detection, pulldown experiments and even immunotherapy. Having been discovered in 1995 during an in vitro screening for antibodies against cytomegaloviral proteins,[4] the A3C5 antibody is an established molecular tool for specific recog- nition of proteins. By tagging cell surface proteins with an epitope specifically recognized by A3C5 (being a minimal peptide sequence of 11 amino acids), one is easily able to detect tagged proteins via immunofluorescence microscopy, FACS or one may purify them via pulldown experiments. Through the latter, one may also screen for in vivo interaction partners of the tagged protein.

Nanoluciferase

Fireflies have fascinated mankind for millenia. The concept of bioluminescence indeed has a great meaning for several invertebrate species, allowing communication with other individuals, signaling receptiveness or deterring predators.[5] The most common enzyme responsible for the creation of bioluminescence are the luciferases (from the latin words ’lux’ and ’ferre’, meaning ’light-carrier’). These enzymes, among others found in fireflies and deep-sea shrimp, commonly consume a substrate called luciferin as well as energy in the form of ATP or reduction equivalents in order to create light-emission through oxidation. The underlying mechanism hereby relies on the creation of an instable, highly excited intermediate under the consumption of energy. This high-energy intermediate then spontaneously falls back into a state of lower energy, emitting the energetical difference as visible light. While mainly being used as a folded, stabilizing element at the N-terminus, the nanoluciferase could also be used for advanced binding studie via luciferase assays.

Luciferases have also found their way into biotechnological applications.[6] The simplistic concept of creating visible (and thus easily measurable) light makes luciferases ideal reporters for the expression of proteins via a corresponding assay. This project also makes use of a luciferase for the determination of expression levels of the surface receptor. The monomeric luciferase used in this project, the so-called ’NanoLuc-RTM-'[7] (due to terms of simplicity referred to as ’nanoluciferase’ in the following), can be fused to other proteins in order to make their expression visible and quantifiable. This engineered luciferase emits a steady, easily detectable glow when exposed to its substrate, while being only 19 kDa large and being brighter, more specific and steadier than other luciferases commonly found in nature. Using luciferases offers several advantages over fluorescent proteins, including smaller size and decreased damage to cells during measurements, as no excitation is necessary for light emission.

===mRuby 3=== Having originally been engineered as a monomeric form of the red fluorescent protein eqFP611, mRuby variants have been some of the brightest red fluorescent proteins available. [8] With an excitation maximum at a wavelength of 558 nm and an emission wavelength maximum of 605 nm, the resulting stokes shift of 57 nm makes mRuby a good choice for fluorescent microscopy imaging and, thus, allows the visualization of the receptor in its cellular environment by being fused to the C-terminus of the transmembrane domain. mRuby is especially powerful for the fusion with receptors - not only due to its small size and high stability, but also due to the fact that, in comparison with eGFP, it appears up to 10 times brighter in membrane enviroments. The mRuby variant used here is mRuby 3, having been engineered for even more improved brightness and photostability.[9]

Strep-tag II

The Strep-tag II is an eight amino acid peptide sequence that specifically interacts with Streptavidin and can thus be used for easy one-step purification of the receptor via affinity chromatography. [10]

CMV promoter

If much is good, more must be better. Last but not least, we of course need our receptor to be expressed to a good extent for efficient cross-linking, so that a high avidity for the interaction may be reached. The CMV promoter (taken from the parts registry, BBa_K74709) enables constitutively high expression of the receptor.

Protein targeting

Essential to a protein's function is not only its activity or binding properties, but also its presence at the right time, at the right place. Just like in real estate, the motto here is 'location, location, location'. One of the most ubiquitous elements for protein targeting is the signal peptide, which enables the translocation of proteins to the ER, from where their journey may continue to the place of function. Proteins containing a signal peptide include transmembrane proteins, secreted proteins, proteins of the ER itself, proteins of the Golgi apparatus and several more. For our project, signal peptides constitute a crucial part for many constructs, being used for targeting of transmembrane proteins to the cell surface, targeting proteins to the ER and the secretion of proteins.

Transmembrane domains

The Cell

BioBrick-compatible vectors for mammalian cells: transient tranfection & stable integration

- Abbildung pDSG/pcDNA5 vektoren

- Abbilgung mit stabiler Integration, Zeocin-Test, genomische PCR

Subcellular protein localization using fluorescence microscopy

Quantification of functionalized membrane proteins using flow cytometry

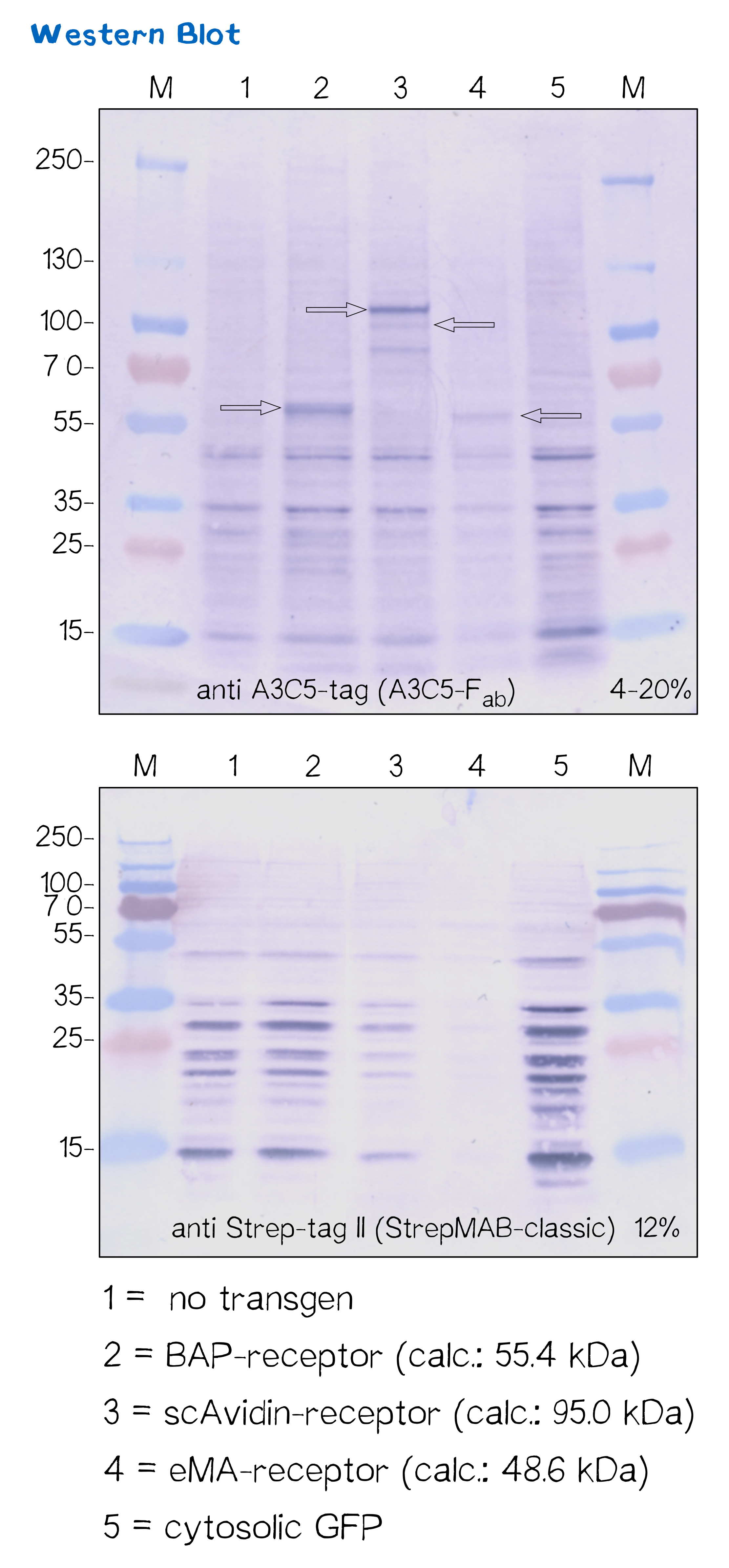

Immunochemical detecton of functionalized membrane protein using Western Blot

| Receptor | BioBrick | Amino acids | Moelcular mass [Da] |

| BAP-Receptor | [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2170000 BBa_K2170000] | 507 | 55 440 |

| eMA-Receptor | [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2170001 BBa_K2170001] | 448 | 48 618 |

| scAvidin-Receptor | [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K2170002 BBa_K2170002] | 877 | 95 028 |

Quantification of mRNA expression levels by RT-q-PCR

High resolution imaging using scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

References

- ↑ Chen, I., Howarth, M., Lin, W., & Ting, A. Y. (2005). Site-specific labeling of cell surface proteins with biophysical probes using biotin ligase. Nature methods, 2(2), 99-104.

- ↑ Kozak, M. (1987). An analysis of 5'-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic acids research, 15(20), 8125-8148.

- ↑ http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP

- ↑ Alexander, H., Harpprecht, J., Podzuweit, H. G., Rautenberg, P., & Müller-Ruchholtz, W. (1994). Human monoclonal antibodies recognize early and late viral proteins of human cytomegalovirus. Human Antibodies, 5(1-2), 81-90.

- ↑ Case, J. F. (2004). Flight studies on photic communication by the firefly Photinus pyralis. Integrative and comparative biology, 44(3), 250-258.

- ↑ Gould, S. J., & Subramani, S. (1988). Firefly luciferase as a tool in molecular and cell biology. Analytical biochemistry, 175(1), 5-13.

- ↑ Hall, M. P., Unch, J., Binkowski, B. F., Valley, M. P., Butler, B. L., Wood, M. G., ... & Robers, M. B. (2012). Engineered luciferase reporter from a deep sea shrimp utilizing a novel imidazopyrazinone substrate. ACS chemical biology, 7(11), 1848-1857.

- ↑ Kredel, S., Oswald, F., Nienhaus, K., Deuschle, K., Röcker, C., Wolff, M., ... & Wiedenmann, J. (2009). mRuby, a bright monomeric red fluorescent protein for labeling of subcellular structures. PloS one, 4(2), e4391.

- ↑ Bajar, B. T., Wang, E. S., Lam, A. J., Kim, B. B., Jacobs, C. L., Howe, E. S., ... & Chu, J. (2016). Improving brightness and photostability of green and red fluorescent proteins for live cell imaging and FRET reporting. Scientific reports, 6.

- ↑ Schmidt, T. G., & Skerra, A. (2007). The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nature protocols, 2(6), 1528-1535.