<!DOCTYPE html>

RESULTS

Final experimental data

GOLD MEDAL: irrE BioBrick enables E. coli to persist in medical lubricant

Diagram to show different growth of wild type E.coli vs. IrrE E.coli in 40% Lubricant 60% LB using Absorbance at 600nm

From the data shown in the graph above it clearly shown that the E.Coli transformed with IrrE grows better in the 40%Lubricant/60%LB solution in direct comparison with the Wild type E.Coli, which hardly grew at all. This data thus suggests that with the IrrE the E.Coli is better adapted to living in, which would allow further studies being conducted on the maximum concentration of Lubricant it can be grown in. Furthermore once that has been determined the pathogen detecting aspect of the concept can be realised. Thus overall this experiment has allowed us to show that IrrE increases the growth of the E. Coli in the Superdrug Lubricant containing: purified water, glycerine, Carbopol 940, Triethanolamine and Sodium Butyl Paraben. This supports the previous experiments that concluded that IrrE allows for better growth in saline conditions[iv], except this time in Superdrug Lubricant.

For further conceptualisation and experimentation it should be taken into consideration that within a commercialisable product the bacteria will not be under ideal growth conditions and the nutrients will be a limiting factor, especially when considering that the lubricant concentration will have to be a lot higher than in this experiment.

SILVER: Lycopene BioBrick

Hypoxia experiment: Inducing oxidative stress

mNARK lycopene enables ecoli growth under Hypoxia conditions

Hypoxia is a condition in which cells are deprived of oxygen due to low concentration of oxygen in the extracellular milieu. In humans, low oxygen levels in the blood affect tissues. Oxygen is essential for diverse cellular functions, such as catabolic and anabolic processes, and low intracellular concentrations have a negative impact on cell functions and survival.

Oxygen deficit can have a severe impact on cellular function, as seen in cell stress. The inability of cells to effectively manage cellular stress over time has been linked to cellular ageing and age-related diseases (Haigis and Yankner, 2010; Poljšak and Milisav, 2012). Cellular stress leads to deregulation of intracellular processes, as both the structure and function of macromolecules are compromised. Furthermore, high amounts of ROS have been implicated in cellular stress and ageing (Poljšak and Milisav, 2012).

We performed an additional assay expressing lycopene under the mNARK promoter, to test if the cells could survive longer under hypoxia-induced stress. E. coli cells transformed with this construct were compared with the wild type TOP10 E. coli (W/T) monitoring growth and division via optical density (OD) at 600 nm, at specific time points – 3 hours and 16 hours following withdrawal of oxygen.

mNARK-Lyco cells had a higher OD compared to the wild type cells. Cells exposed to hypoxia were also compared with the cells that were grown with oxygen. Most cells still survived despite the presence of hypoxia.

Furthermore, with regards to W/T cells, a depletion in the oxygen concentration caused a drop in cell growth and division, as reflected in decreased OD measurements. However, growth and division of mNARK-Lyco-containing cells was maintained in oxygen-deficient environment during the 16-hour time test period.

This shows that our BioBrick construct (mNARK-Lyco) was able to ensure cell growth and division in oxygen-deficient environment.

Inducing oxidative stress through other ways - copper and --

add text here

GOLD MEDAL: Spy promoter BioBrick functions as pH switch

The deterioration of oral health in the elderly is accompanied by an increased prevalence of caries and periodontal disease, which are risk factors for some systemic diseases and nutrition problems (1). The oral cavity is inhabited by a wide range of interacting communities of metabolically and structurally organized microorganisms which synthesize an extracellular polysaccharide matrix (EPS) enabling them to adhere to the surface of the teeth and assemble in matrix-embedded biofilms. Progressing biofilm accumulation puts the bacteria under increasing metabolic stress, which leads to localized metabolite and acid accumulation and a shift in the dynamic homeostasis towards acid-tolerating species such as Gram-positive Streptococcus mutans (3). A resultant decrease in pH causes tooth demineralization and constitutes a mechanism of dental caries.

In our project, we designed a biosynthetic device to serve as an alternative in preventative dental care for the elderly. We decided to target pH and an indicator of deteriorating oral health and use it as an system to regulate the relate of antimicrobial peptide known as mutacin III, is effective against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria implicated in dental caries, e.g. other strains of Streptococcus mutans and Actinomyces naeslundii, while Gram-negative bacteria are resistant to inhibition (5).

An existing BioBrick in the iGEM registry (BBa_K239001), designed to detect misfolding of proteins in the periplasm or shear stress has been further characterised to demonstrate the BioBrick functions as a pH inverter.

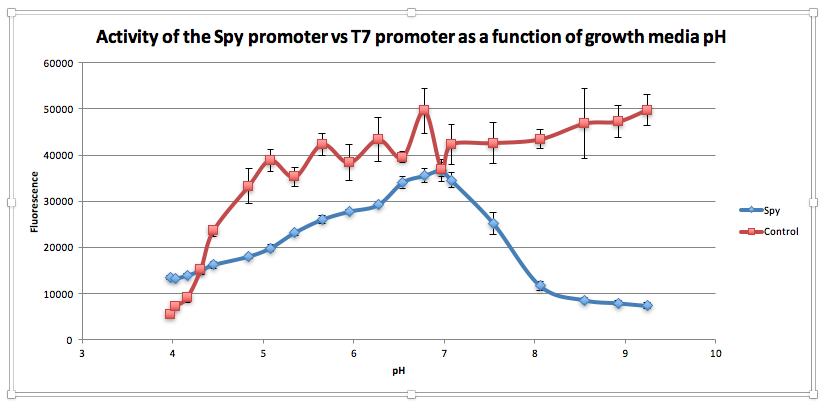

Compared to the control, as pH increases from 3.97 to 6.78, GFP expression gradually increases for E. coliwith BBa_K239009. The maximum GFP expression is observed at 6.78. GFP expression increases from 13,556.25 at pH 3.97 to 35,569 at pH 6.78. Beyond this maximum, there is a sharp decline in GFP expression as the starting LB broth increases in alkalinity, falling to 7,394 at pH 7,394. Conversely, for the control, a sharp increase is observed from pH 5393.5 at 3.97 to 38854.5 at pH 5.08. After this, the general trend is one of increasing fluorescence as pH increases, but the increase is more gradual.

From this experiment, we have established that BBa_K239009 (Spy Promoter) previously used to characterise protein misfolding can be used as a pH-sensitive promoter, as well. Thus, we have improved the function and characterization of an existing BioBrick Part.

References

- Gil-Montoya JA, de Mello ALF, Barrios R, Gonzalez-Moles MA, Bravo M. Oral health in the elderly patient and its impact on general well-being: a nonsystematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:461–7.

- Rouxel P, Tsakos G, Chandola T, Watt RG. Oral Health-A Neglected Aspect of Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2016 Mar 12.

- Anderson MH. Changing paradigms in caries management. Curr Opin Dent. 1992 Mar;2:157–62.

- Qi F, Chen P, Caufield PW. Purification of mutacin III from group III Streptococcus mutans UA787 and genetic analyses of mutacin III biosynthesis genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999 Sep;65(9):3880–7.

- Hillman JD, Johnson KP, Yaphe BI. Isolation of a Streptococcus mutans strain producing a novel bacteriocin. Infect Immun. 1984 Apr;44(1):141–4.

- Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Food Microbiology: Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005 Oct;3(10):777–88.

- Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Bacterial lantibiotics: strategies to improve therapeutic potential. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2005 Feb;6(1):61–75.

- Sahl HG, Jack RW, Bierbaum G. Biosynthesis and biological activities of lantibiotics with unique post-translational modifications. Eur J Biochem. 1995 Jun 15;230(3):827–53.

- Moll GN, Roberts GC, Konings WN, Driessen AJ. Mechanism of lantibiotic-induced pore-formation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1996 Feb;69(2):185–91

- Smith L, Zachariah C, Thirumoorthy R, Rocca J, Novák J, Hillman JD, et al. Structure and dynamics of the lantibiotic mutacin 1140. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2003 Sep 9;42(35):10372–84.

- Abee T. Pore-forming bacteriocins of Gram-positive bacteria and self-protection mechanisms of producer organisms. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995 Jun 1;129(1):1–9.

- Saising J, Dube L, Ziebandt A-K, Voravuthikunchai SP, Nega M, Gotz F. Activity of Gallidermin on Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis Biofilms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Nov 1;56(11):5804–10.

- Draper LA, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Lantibiotic Resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2015 Jun;79(2):171–91.

- Hagiwara A, Imai N, Nakashima H, Toda Y, Kawabe M, Furukawa F, et al. A 90-day oral toxicity study of nisin A, an anti-microbial peptide derived from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, in F344 rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 Aug;48(8-9):2421–8.

- Delves-Broughton J. Nisin and its application as a food preservative. Int J Dairy Technol. 1990 Aug;43(3):73–6.

Superoxide Dismutase 3 Biobrick: GFP titration experiment