Modelling

Introduction

As part of our project, we are designing a novel detection mechanism for the cyanobacterial toxin microcystin using live

Saccharomyces cerevisiae

yeast cells. The essential principle is to couple the yeast’s natural response against the toxin to the production of a yellow fluorescent protein, Venus.

In our concept for the detection mechanism, a sample of water, either contaminated with microcystin or not, is supplemented to a culture of live yeast cells. The detection mechanism then functions as follows: the genetically modified yeast take the toxin in through a specific transporter (QDR2 from

S. cerevisiae

strain VL3), after which the toxin inhibits the function of protein phosphatases in the cell. This leads to an abundance of chemical reactions that produces an accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) (Valério et al. 2014). The cell naturally fights against this accumulation of harmful oxygen species through a mechanism known as Oxidative Stress Response, or OSR.

Our detection mechanism is based on modifying natural OSR to produce a visible response. To this end, we have chosen three naturally occurring promoters from genes involved in the yeast’s oxidative stress response: CTT1, CPP1 and TSA1.

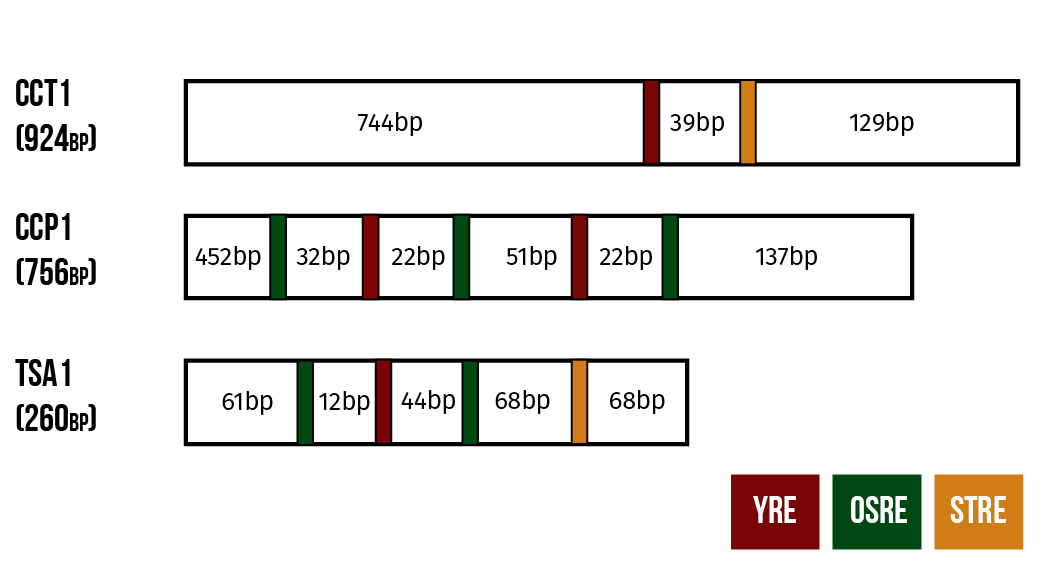

These promoters are structured as follows. CTT1 has a single binding site for a transcription factor known as YAP1 and at least one binding site for the factor MSN2. Meanwhile, the other two promoters have binding sites for Yap1p and for a third transcription factor Skn7p. CCP1 has one binding site for YAP1 and two for Skn7p while TSA1 has two binding sites for Yap1p and three for Skn7p. (He et al. 2005)

In our constructs, these promoters are coupled to genes expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). We hope to be able to get an estimate of the microcystin content of the sample from the fluorescent activity of the live yeast cells.

To study our detection mechanism mathematically, we have created a model for the transcription factors Yap1p and Skn7 and their activation in the cells, hoping to determine production patterns and thresholds of YFP and provide suggestions for optimal promoter design for future iterations of the project.

“ As an Oxidative Stress Response mechanism, Yap1p is localized and accumulated in the nucleus. ”

Biological background

Regulation of the Transcription Factor YAP1

Yap1p is activated by spatial accumulation into the nucleus. The accumulation occurs by inhibition of the export of Yap1p outside the nucleus. (Toledano et al. 2004) More specifically, Yap1p contains two kinds of localization signals, a DNA-binding/nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence in the N-terminus, and a nuclear export signal (NES) in its C-terminus. Under normal conditions, NES activity is higher compared to NLS activity and thus, Yap1p is exported out of the nucleus via the transporter Crm1p which recognizes the NES sequence (Yan et al. 1998). Under oxidative stress the NES is covered with the help of the proteins Gpx3p/Orp1p and Ybp1p which prevents Yap1p from leaving the nucleus, causing the protein to accumulate (Veal et al. 2003). Yap1p is transported into the nucleus through the transporter Pse1p which recognizes the NLS sequence (Isoyama et al. 2001). Pse1p is not affected by the oxidative stress (Isoyama et al. 2001). After nuclear accumulation, Yap1p targets Yap1p response element (YRE) and activates the target gene.

Orp1p is a protein inside the yeast cell which can recognize intracellular H2O2 and transfer this information to Yap1p. Orp1p causes Yap1p to form an intracellular disulfide bond which covers the NES, and thus prevents Yap1p from leaving the nucleus.

In literature two mechanisms are suggested for the deactivation of Yap1p-activated OSR genes:

1) Thioredoxin (Trx) is responsible for reducing Yap1p and Orp1p (transcription factor and H2O2 sensor) (He et al. 2005). Since Trx2 is one of the target genes of Yap1p, Yap1p is autoregulated (He et al. 2005). Another mechanism of autoregulation occurs through Prx enzymes such as Tsa1 and Tsa2, which reduce the amount of H2O2 inside the cell by oxidising it to water, and thus inhibit the activity of Orp1 which decreases the activation of Yap1p. Prx enzymes are also targets of Yap1p. (Toledano et al. 2004)

2) Another suggested mechanism of Yap1p regulation is degradation of Yap1p after it has targeted the YRE. The degradation of Yap1p is induced by Not4 and it is tightly linked to the nuclear accumulation and DNA binding of Yap1p. (Gulshan et al. 2012)

Regulation of transcription factor Skn7p activity

The activation of transcription factor Skn7p under oxidative stress is not completely clear. Although the complete mechanism is not known, some models have been suggested. It is known that Skn7p is located in the nucleus in both normal and stress conditions and that some unknown kinase plays a role in its activation. (He et al. 2009) In addition, He et al. 2009 concluded that Yap1p affects the activity of Skn7p. According to their model, Skn7p forms a weak interaction with Yap1p, which is then strengthened through phosphorylation by an unknown kinase. The formation of this strong interaction with Yap1p and Skn7p activates the OSR genes.

Regulation of transcription factor Msn2/4p

Msn2/4p are transcription factors that regulate genes involved in various kinds of stress, including stress related to nutrition, heat, osmotic and acid equilibrium as well as oxidative stress. Activation of Msn2/4p occurs with a mechanism similar to Yap1p. In normal conditions Msn2/4p is located in the cytoplasm. In response to stress Msn2/4p accumulates into the nucleus. This nuclear localization is coordinated by PKA (protein kinase A) (Luschak 2010).

PKAs are kinase enzymes that are activated by cAMP and regulated by hormones such as glucagon and epinephrine. PKA phosphorylates Ser260 of Msn2, which under normal conditions prevents the localization of Msn2/4p into the nucleus (Luschak 2010). Under oxidative stress Msn2 is relocalized inside the nucleus by a signal which is transmitted by Trx1p and Trx2p (Boisnard et al. 2009). The exact mechanism of signal transmission is unknown, but it is not affected by PKA or cAMP (Boisnard et al. 2009). It has also been speculated that an unknown phosphatase dephosphorylates the Msn2/4p before it can enter into the nucleus (Boisnard et al 2009). When the cell starts to adapt to stress Msn2p quickly leaves the nucleus through the transporter Msn5p (Luschak 2010).

“ The activation mechanisms of transcription factors Yap1p and Skn7 are higly correlated. ”

Models of our detection mechanism

Our detection mechanism is based on the use of promoters of genes that are regulated during oxidative stress response in order to express a Yellow Fluorescent Protein (YFP). The fluorescence intensity of the YFP can be measured with a fluorometer. With the aim of understanding this phenomenon better, we have created simplified molecular and mathematical models of the mechanisms involved. Specifically, we are modelling the interactions involved in the regulation of the activity of the transcription factors Yap1p/Skn7p and Msn2/4p.

Simplified Molecular Model

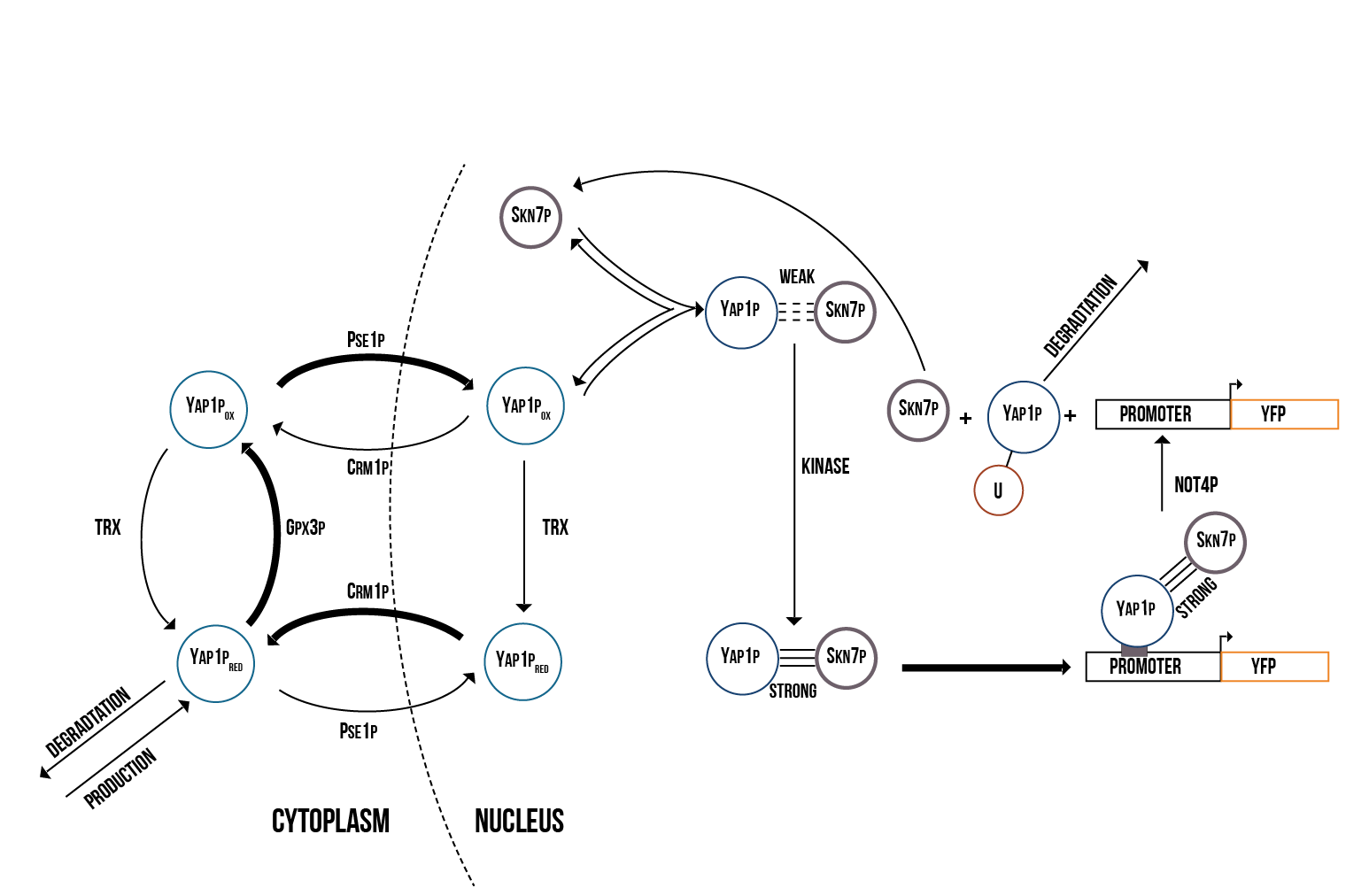

Since the activations of Yap1p and Skn7p are highly correlated, we created a molecular model including both transcription factors. Furthermore, we decided to use the suggested model of Yap1p degradation in which the Not4 protein induces its degradation after Yap1p has targeted the YRE. The molecular model of the activation of Yap1p and Skn7p is presented in figure 2.

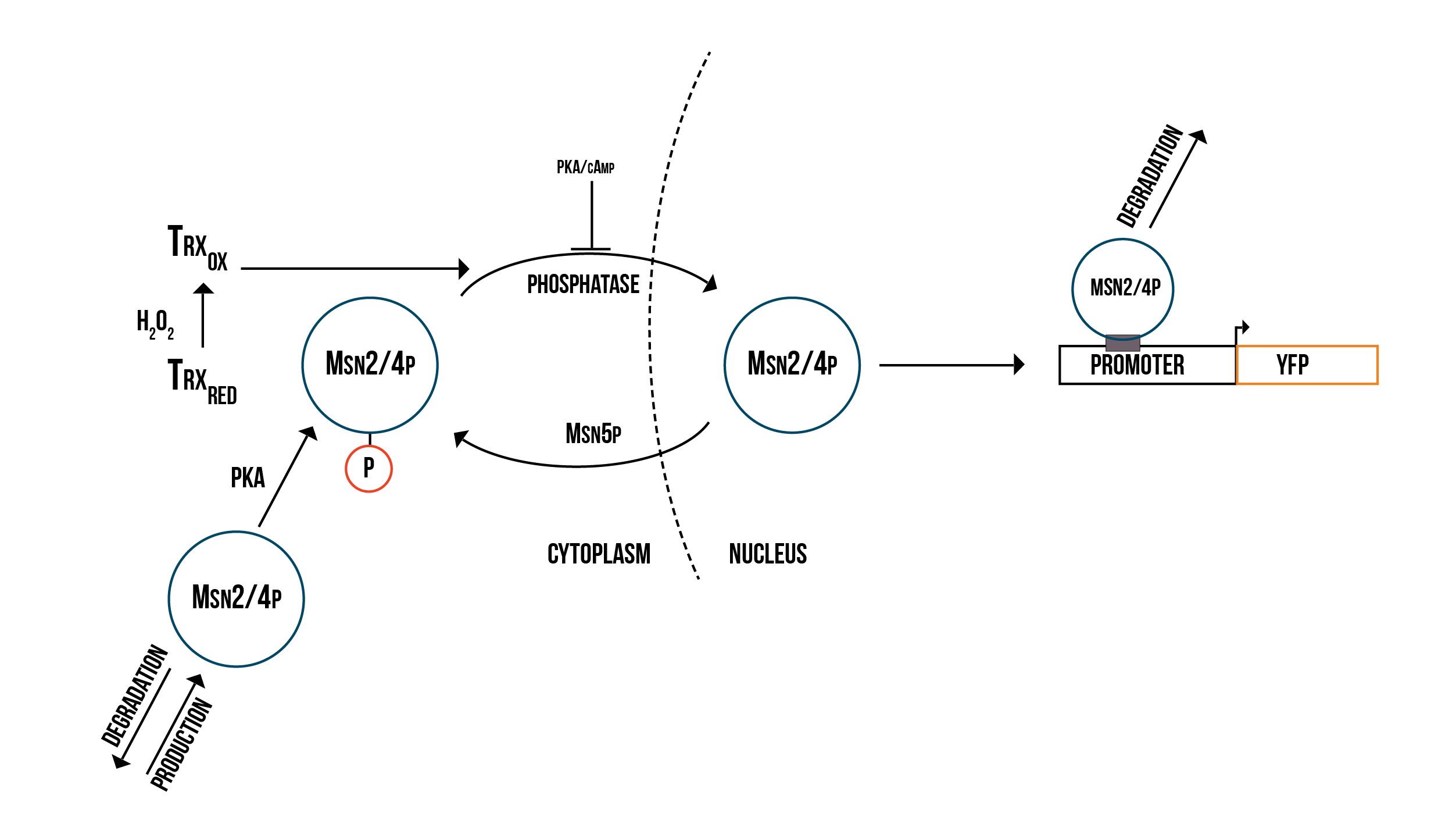

In addition to Yap1p/Skn7p, we modelled the activation of two other transcription factors involved in OSR, namely Msn2p and Msn4p, which in the literature are usually merged to Msn2/4p. The molecular model we created is presented in figure 3.

We decided to simplify the mechanism which we presented above in order to be able to measure the YFP production potential of each of the promoters we are using.

Simplified YAP1P/SKN7 regulation mechanism

Notation - we will denote our variables as follows:

- Transcription factor YAP1P in its reduced form and contained in the nucleus is denoted by NR .

- Transcription factor YAP1P in its reduced form and contained in the cytoplasm is denoted by CR .

- Transcription factor YAP1P in its oxidized form and contained in the nucleus is denoted by NO .

- Transcription factor YAP1P in its oxidized form and contained in the cytoplasm is denoted by CO .

- The oxidative species Gpx3 is denoted by GPX3 .

- The transporter Pse1p is denoted by PSE1P .

- The transporter Crm1 is denoted by CRM1 .

- The Trx sensor is denoted by TRX .

- The transcription factor Skn7 is denoted by Skn7 .

- The weak bond between the oxidized nucleic Yap1p and the nucleic Skn7 is denoted by w(Yap1p:Skn7) .

- The strong bond between the oxidized nucleic Yap1p and the nucleic Skn7 is denoted by s(Yap1p:Skn7) .

- The kinase responsible for stabilizing the Yap1p : Skn7 bond is denoted by kinase .

- The degradation element NOT4 which is responsible for yap1p degradation in the nucleus is denoted by NOT4 .

- The active Yap1p marked for degradation in the nucleus via the NOT4 element is denoted by S(YAP1P:SKN7):NOT4 .

- The complex of Yap1p and Skn7p that is bound to the promoter is denoted by protein_builder .

- The total amount of YFP is denoted by protein .

Conservation Laws

We will define four conservation laws in the presence of oxidative stress which we will use throughout our model; these conservation laws help simplify our equations and model.

- C1: The kinase activity in the nucleus is constant.

- C2: The quantity of transcription factors binding sites is constant (as is the number of constructs).

- C3: The quantity of nucleic Skn7 transcription factor is constant.

- C4: The quantity of NOT4 element is constant inside the nucleus.

Reactions for the Yap1p/Skn7 Molecular Model

For the binding of molecules we will use the symbol ”:”.

- (Reaction 1) CR : PSE1P ⇒ NR. This reaction represents the transport of the transcription factor YAP1P from the cytoplasm into the nucleus with the help of the transporter Pse1p. We will use the expression pse1p_reduced to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 2) NR : CRM1 ⇒ CR. As a regulatory mechanism for the YAP1P in the nucleus, the transporter (Crm1) exports the transcription factor outside of the nucleus. The reaction rate of this reaction will be denoted by Crm1.

- (Reaction 3) CO : PSE1P ⇒ NO. The YAP1P transcription factor can freely move from the cytoplasm into the nucleus through Pse1p transporter. This phase is not inhibited by oxidative stress. We will use pse1p_oxidised to denote the reaction rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 4) CR : GPX3 ⇒ CO. The YAP1P transcription factor binds to the protein GPX3 after it senses a bigger ROS quantity and gets oxidised. We will use Gpx3 to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 5) CO ⇒ CR. This reaction represents the transcription factor getting reduced back once the ROS quantity decreases with the help of TRX. We will use Trx_cytoplasm to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 6) NO ⇒ NR. This reaction is equivalent to the one above, but it occurs in the nucleus, where the oxidised YAP1P gets reduced with the help of TRX. We will use Trx_nucleus to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 7) NO + SKN7 ⇒ (NO:SKN7)w. This reaction depicts the weak binding of the nucleic oxidised Yap1p to the nucleic Skn7 transcription factor. We will use k1 to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 8) (NO:SKN7)w + kinase ⇒ (NO:SKN7)s. This reaction represents the strong bond between the nucleic oxidised Yap1p and the nucleic Skn7 transcription factors after the kinase binds to the weak bond. We will use kinase+ to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 9) S(NO:SKN7) + Construct ⇒ protein_builder . This is the binding reaction of the yap1p:skn7 complex to the binding site of the gene denoted by Construct. We will use Construct_binding to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 10) protein builder ⇒ S(NO:SKN7):NOT4 + Construct. This is representing the binding of the NOT4 species to the YAP1P/SKN7 complex which causes its separation from the gene. We will use Not4+ to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 11) CR ⇒ . This reaction represents the degradation of the YAP1P contained in the cytoplasm. We will use cr_deg+ to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 12) ⇒ CR. This reaction represents the production of YAP1P in the cytoplasm. We will use cr_prod to denote the rate of this reaction.

- (Reaction 13) ⇒ protein. This reaction represents the production of yellow fluorescent protein from the YAP1P/SKN7 complex bind to the promoter of the gene. The rate at which YFP is produced will be denoted by protein+.

- (Reaction 14) S(NO:SKN7):NOT4 ⇒ SKN7. This reaction represents the degradation of the oxidised YAP1P by the ubiquitin left by the NOT4. We will denote the rate of this reaction by ubiquitinb+.

- (Reaction 15) YFP ⇒. This reaction represents the natural degradation of YFP. We will denote the rate of this reaction by YFP_deg.

Reactions for the Msn2/4p molecular model

- (Reaction 1) C-Msn2/4p ⇒. This reaction represents the natural degradation of Msn2/4p.

- (Reaction 2) ⇒ C-Msn2/4p. This reaction represents the production of Msn2/4p in the cytoplasm.

- (Reaction 3) C-Msn2/4p ⇒ N-Msn2/4p. This reaction represents the transportation of dephosphorylated Msn2/4p into the nucleus.

- (Reaction 4) C-Msn2/4p : PKA ⇒ C-Msn2/4p_phos. This reaction represents the dephosphorylation of Msn2/4p by PKA.

- (Reaction 5) C-Msn2/4p_phos : phosphatase ⇒ C-Msn2/4p. This reaction represents the phosphorylation of Msn2/4p by a phosphatase.

- (Reaction 6) C-Msn2/4p_phos ⇒ N-Msn2/4p_phos. This reaction represents the transportation of Msn2/4p into the nucleus, inhibited by PKA/cAMP.

- (Reaction 7) N-Msn2/4p_phos ⇒ C-Msn2/4p_phos. This reaction represents the transportation of Msn2/4p into the nucleus, aided by Msn5p.

- (Reaction 8) N-Msn2/4p_phos + Promoter ⇒ protein_builder. This reaction represents the binding of the nucleic phosphorylated Msn2/4p to the promoter.

- (Reaction 9) protein_builder ⇒ Promoter. This reaction represents the natural degradation of Msn2/4p after it has served its purpose.

Mathematical Model

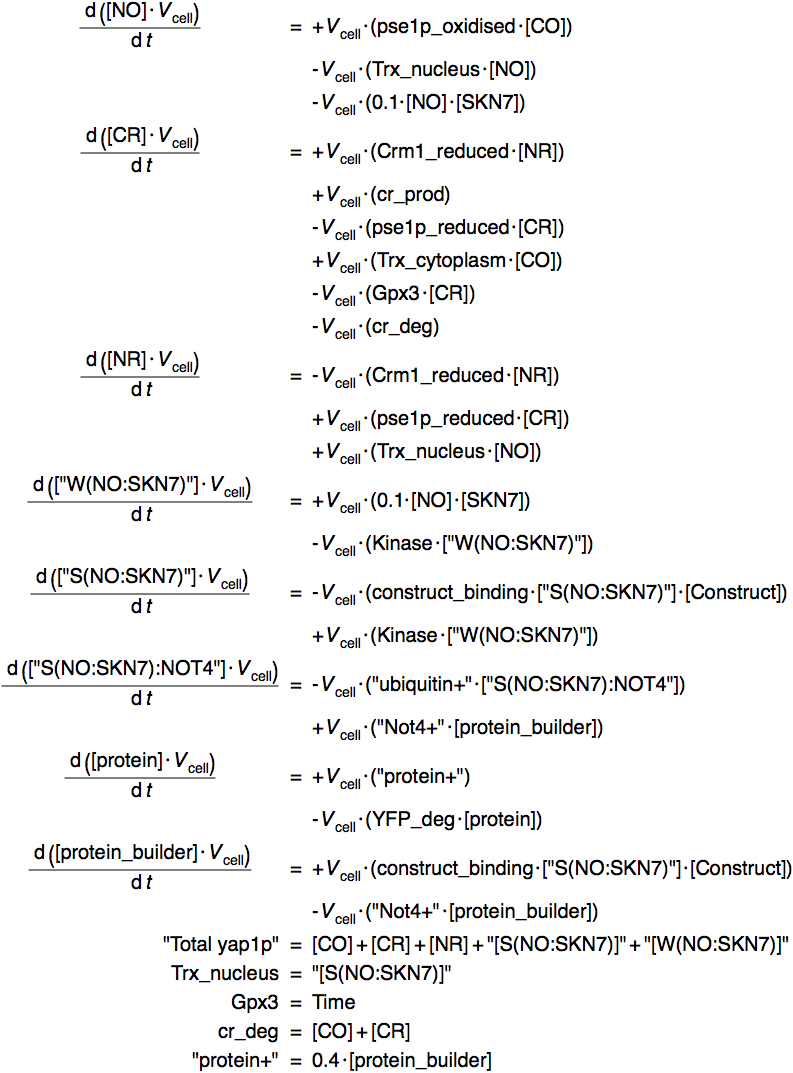

Differential Equations of the Associated Mathematical Model of the Yap1p:Skn7 Molecular Model

In figure 4, we show the differential equations associated to the molecular model obtained above. These correspond to the main species of interest in our model and were used for running our numerical simulations.

“ We observe that as the rate of kinase activity lowers, the quantity of active genes approaches a smooth logarithmic curve ”

Numerical simulations

We used the software COPASI to run time course simulations of the simplified molecular model presented above as a mass-action model. We decided to make use of a mass-action model since we are given more freedom of choosing our variables and the interactions between them.

We used the Gpx3 protein quantity as an indicator of oxidative stress based on the previously investigated literature. We decided to use a linear relation of time and Gpx3, by assuming that toxin sensing by Gpx3 increases linearly over time during stress.

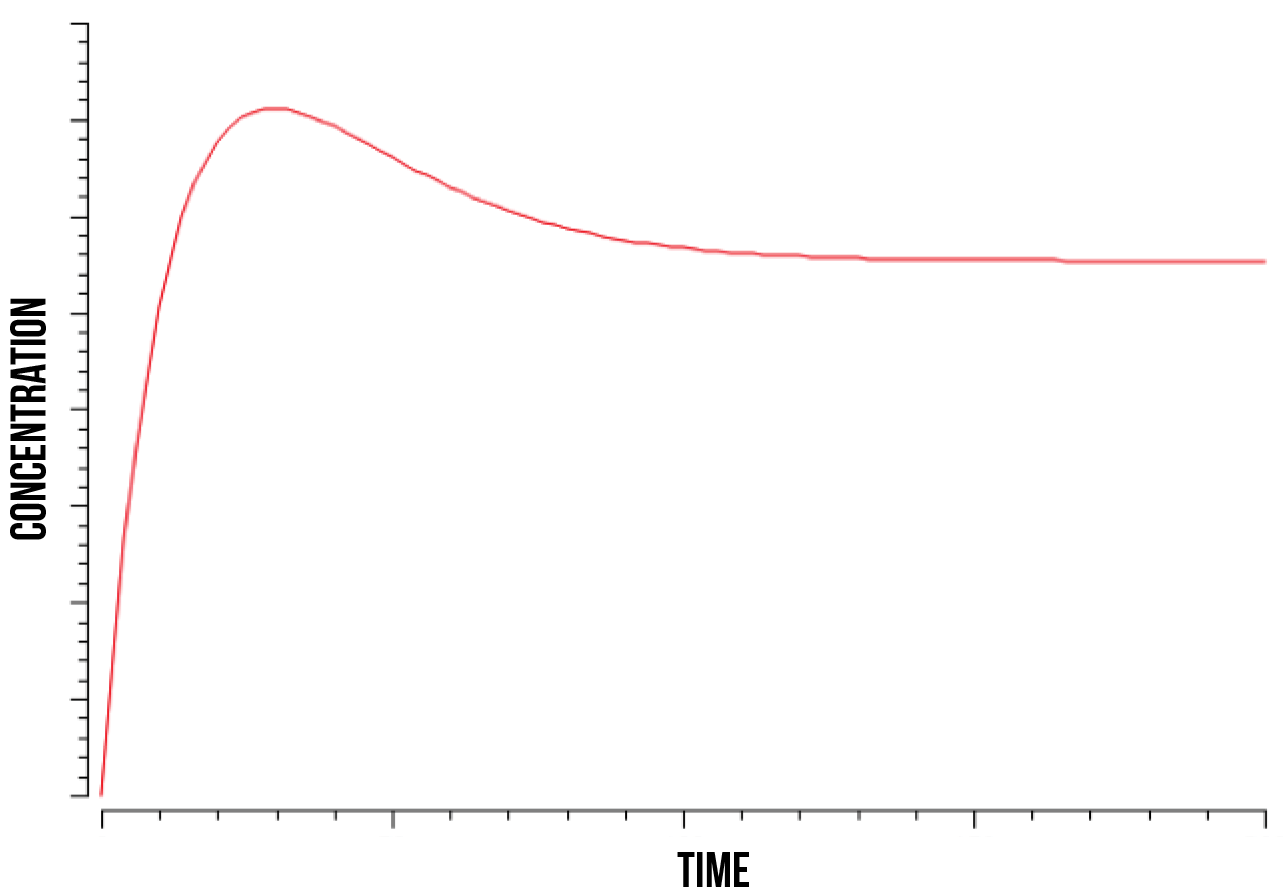

In figure 5, we show a plot of the quantity of oxidised Yap1p:Skn7 complex in the nucleus after a kinase has stabilized the bond. We can observe how its quantity increases until it reaches its peak and then decreases until stabilising again. This phenomenon was observed at wide numeric ranges in the Skn7 concentration and YAP1P localisation rate in the nucleus when in stress.

We also observed that the quantity of the Not4 element directly determines the time point at which the quantity of the strongly bound complex S(NO:SKN7) stabilizes, as well as the total quantity of the complex after stabilization. This was observed at a range of estimated values for Not4 ubiquitin marking and degradation rate. These results accord with the literature (Gulshan et al. 2012), which models Yap1p as being marked for degradation by Not4 after the S(NO:SKN7) complex has decoupled from the promoter.

In order to quantify the potential production of Yellow Fluorescent Protein through the activation of YAP1P and SKN7 complexes, we consider a simplified model of our promoters in which these transcription factor complexes bind to the promoters at a linear rate. We assume that the activation of the promoter is directly dependent on the quantity of transcription factor complexes binding to it.

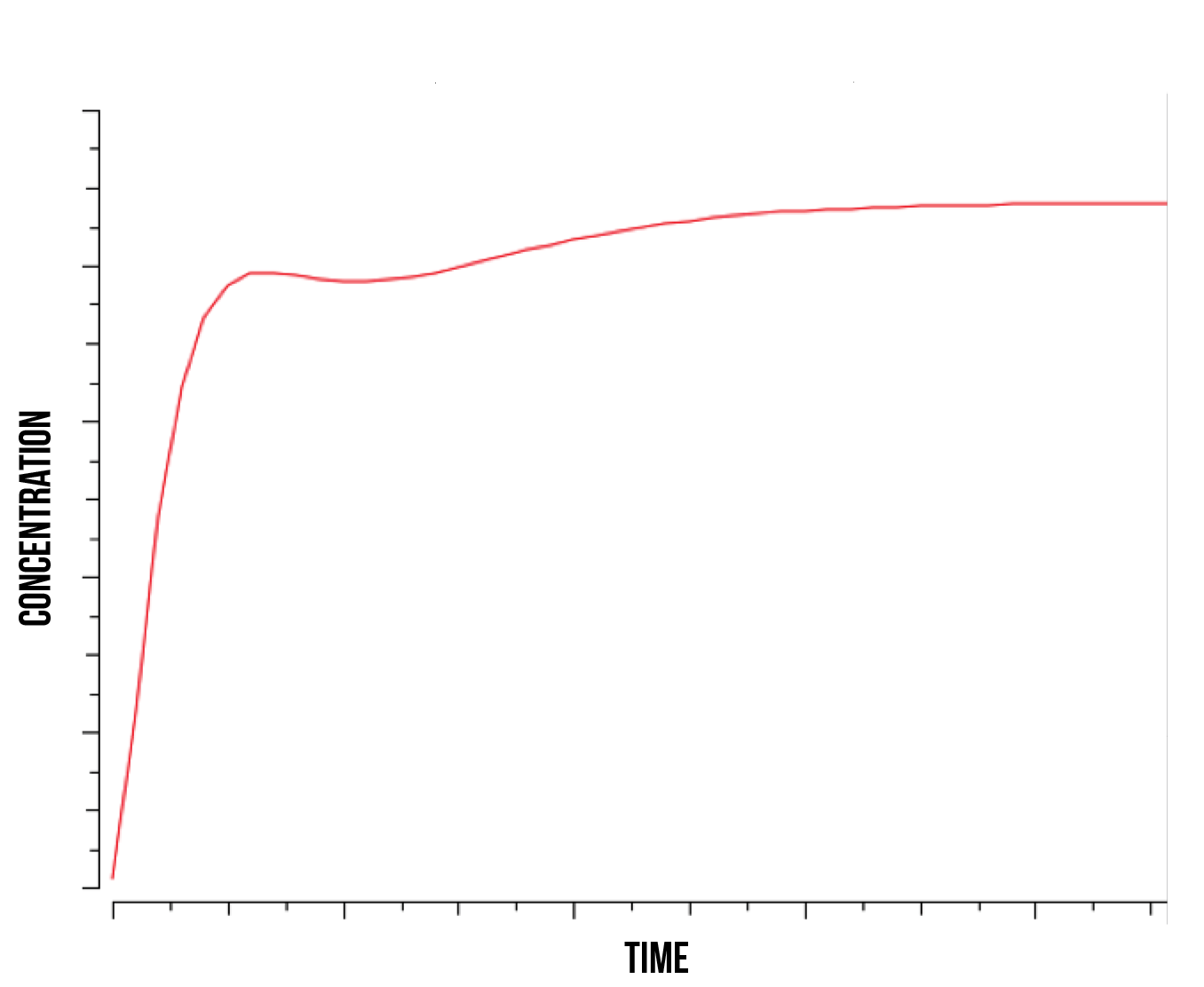

We modelled our active gene using a time course model directly dependent on the quantity of the S(NO:SKN7) complex. We plotted this active gene concentration with respect to time during stress, as shown in figure 6. We note that the maximum quantity of active genes is determined by the minimum of Skn7p and promoter quantity in the cell. As one can observe in the figure 5, the quantity of active genes increases and stabilises at a nearly logarithmic rate, which depends on the promoter binding and kinase phosphorylation rates.

We note that the above plot is a reference for the overall behaviour of these parameters and does not provide any specific rate or numerical value for gene activation, which must be deduced experimentally. This simulation was run in a range of values of Skn7 nucleic quantity, active site binding probability (rate), total plasmid quantity and degradation rate of YAP1P by NOT4 element in the nucleus.

It is in our interest to determine the relation between the S(NO:SKN7) complex of Yap1p and Skn7 (in a strong bond) and the quantity of active genes present in the nucleus. Understanding this relation could shed some light into the degradation mechanisms of YAP1P during oxidative stress and the role of the kinase responsible for phosphorylating Skn7p. We observe that as the rate of kinase activity lowers, the quantity of active genes approaches a smooth logarithmic curve, suggesting a slower construct saturation and hence a faster linear stabilization of total protein produced. At higher kinase activity rates, our active gene quantity experiences a faster initial slope and subsequent immediate decrease, followed by an increase and stabilization, as shown in figure 7 below.

This suggests a behaviour similar to the S(NO:SKN7) complex, where the role of the kinase is directly responsible for quantity of active genes. We observe an increase in immediate gene activation in the form of S(NO:SKN7) complex and constructs together with a decrease on W(NO:SKN7) complex due to a high kinase activity. This explains the momentaneous decrease in S(NO:SKN7) complex as the Not4 starts degradation and single oxidised Yap1p transcription factor in the nucleus concentration experiences a relative decrease. This also suggests a fast activity and gene activation due to the mechanism of Yap1p transcription factor, followed by a more stable action during the course of stress.

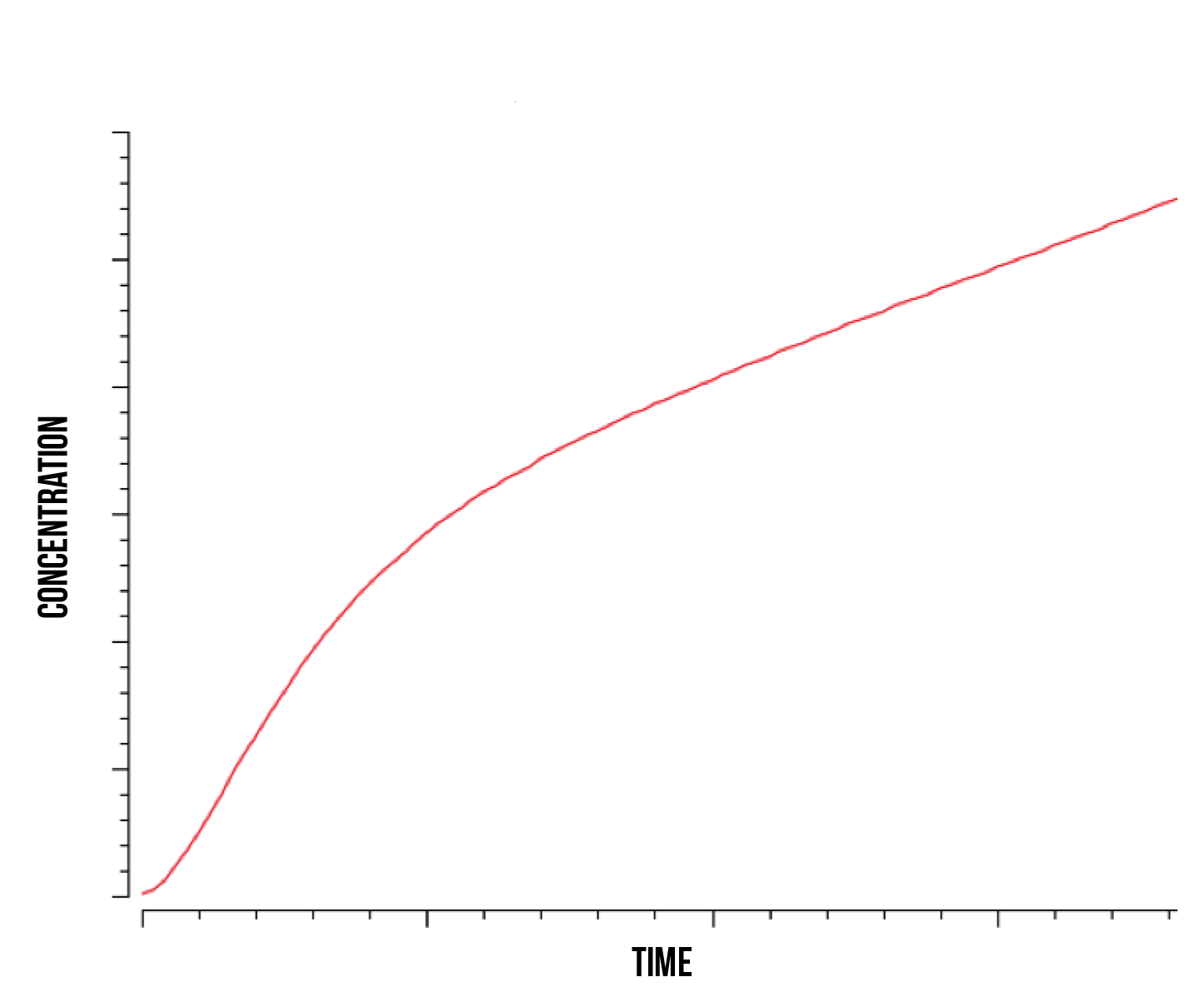

Since we are interested in the overall Yellow Fluorescent Protein production in the nucleus, we plotted the total protein produced as a function of time during stress which is presented in figure 8.

In accordance to the previous plots, we observe a stabilised linear accumulation of produced of protein after the quantity of active constructs has reached its maximum. Before this threshold has been reached, we can observe a nearly exponential increase in protein quantity at the beginning of stress response. This behaviour was observed at both high and low kinase activity rates. It is also worth noting that the stabilized linear protein quantity will eventually become constant as the protein production stops. We observed this phenomenon as Yap1p production rates in the nucleus cannot keep up with the Not4 degradation rate, causing the Yap1p to nearly disappear in the nucleus and stopping its activation of target genes.

As mentioned above, these results also couple with previous literature that classifies the YAP1P and SKN7P transcription factors as fast or immediate response elements in the oxidative stress response (Lushchak 2010), having their highest activity during the beginning of the OSR rather than activating long-term repair mechanisms.

Not4 activity and Yap1p regulation

We compared active gene quantity as a function of the Not4 degradation activity of Yap1p while in complex form bind to the promoter part of the gene. We observed that as the Not4 activity increases, the active gene constructs quantity stabilize at different smaller values but preserves an overall same structure curve which resembles that of the S(NO:SKN7) complex; consequently, we observe a lower initial slope in the protein production, which also stabilizes at a later period in time.

When the Not4 activity is low, we observe a behaviour of the active gene quantity which resembles a smooth logarithmic curve, and in which the quantity of protein produced reaches stability at a sooner period in time with an overall steeper slope.

These results give support to the mechanism suggested at (Glushan et al. 2012) where YAP1P degradation occurs due to NOT4 activity inside the nucleus.

“ Our model supports the hypothesis that Yap1p and Skn7 play a crucial role in the immediate oxidative stress response of the cell ”

References

Boisnard, S., Lagniel, G., Garmendia-Torres, C., Molin, M., Boy-Marcotte, E., Jacquet, M., Toledano, M., Labarre, J., Chédin, S. 2009. H2O2 Activates the Nuclear Localization of Msn2 and Maf1 through Thioredoxins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Eukaryotic Cell, 8(9), pp.1429–1438

Gulshan, K., Thommandru, B., Moye-Rowley, WS., 2012. Proteolytic degradation of the Yap1 transcription factor is regulated by subcellular localization and the E3 ubiquitin ligase Not4. J Biol Chem. 287:26796–26805.

He, X.J. and Fassler, J.S., 2005. Identification of novel Yap1p and Skn7p binding sites involved in the oxidative stress response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular microbiology, 58(5), pp.1454-1467.

He, X.J., Mulford, K.E., Fassler J.S., 2009. Oxidative stress function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Skn7 receiver domain. Eukaryot Cell. 8. pp.768–778.

Isoyama, T., Murayama, A., Nomoto, A., Kuge, S., 2001. Nuclear import of the yeast AP-1-like transcription factor Yap1p is mediated by transport receptor Pse1p, and this import step is not affected by oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 276, pp.21863–21869

Lushchak, V. I., 2010. Oxidative stress in yeast. Biochemistry, 75(3), pp.281-296.

Toledano, M.B., Delaunay, A., Monceau, L., and Tacnet, F., 2004. Microbial H2O2 sensors as archetypical redox signaling modules. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, pp.351-357.

Valério, E., Vilares, A., Campos, A., Pereira, P. and Vasconcelos, V., 2014. Effects of microcystin-LR on Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth, oxidative stress and apoptosis. Toxicon, 90, pp.191-198.

Veal, E.A., Ross S.J., Malakasi, P., Peacock, E., Morgan, BA., 2003. Ybp1 is required for the hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidation of the Yap1 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 278. pp.30896–30904.

Yan, C., Lee L.H., Davis L.I., 1998. Crm1p mediates regulated nuclear export of a yeast AP-1-like transcription factor. EMBO J.17. pp.7416-7429.