DESCRIPTION

The main parts of our proyect

Glycerol

This molecule is produced in high amount in the biofuel industry. It has several uses, but what can we do with the surplus?

Biofilm

Some kinds of microorganisms can adhere to a surface and between them, forming a tridimensional colony that protects them from different risks.

Products

A lot of different products can be easily produced and secreted by the microorganisms, as propionate, plastics, butanol, citric acid...

Introduction

Our project is based on biofilms, communities of bacteria that protect themselves from external factors by an exopolysaccharides coat. We decided to modify Pseudomonas putida so it will form and disperse the biofilm at our will, and afterwards we have modified them in order to increase and optimise the consumption of glycerol, as well as introduce some genes in it so it can produce propionate. Finally, all this constructs will converge in a same strain that will be able to operate in a reactor under industrial conditions. For this purpose, we used a molecular ON/OFF switch which is regulated by a simple compound, salicylate.

Why biofilms?

A biofilm is a community of bacteria that have attached to a surface and between them, and that have produced an extracellular matrix made out of polysaccharides. These kind of structures are metabolically more active, can protect themselves from a wide variety of environmental dangers and can be active during long periods of time. These properties make biofilms a really useful tool in order to degrade pollutants and waste products and produce new useful compounds, using the biofilm structure as a biotechnological factory. However, these kind of structures have their own cycles, since wild bacteria regulate the formation and dispersion by diverse stimuli and regulation networks.

This means that we will need to manipulate our bacteria in order to achieve a customised and outside-regulated biofilm. Therefore, our first goal is to engineer a bacterial strain which can induct or disperse the biofilm following our instructions, using an ON/OFF molecular switch dependent on a multi-step regulation with different promoters and inductors. The use of biofilm would provide a higher yield than floating bacteria and an easier handling. This module includes the use of both structural and regulatory genes that participate in the biofilm formation cycles.

This system will be implemented in Pseudomonas putida. P. putida is a gram negative soil bacteria that has the ability to produce biofilms. This model organism has a very wide metabolic versatility, adapting itself easily to any kind of carbon source. Besides, its genome has been completely sequence, and there exist many useful tools to manipulate its genetics, as it is the case of the miniTn7 device. In addition, it is also easy to perform deletion mutants in this species, fundamental to one of the branches of the manipulation of the biofilm.

How is the biofilm regulated?

In the Figure 1 you can see the regulation system that controls the induction and dispersion of biofilms in Pseudomonas putida:

Figure 1. Regulation of the biofilm formation and dispersion. There are two complementary systems; one depends on the di-c-GMP (DGC, diguanylate cyclase, and PDE, phosphodiesterase), and the other one controls the amount of adhesion proteins (LapC, which controls the LapA secretion, and LapG, which controls the LapA stability).

LapA is the adhesin responsible of the adhesion of the bacteria to the surface during the biofilm formation process. The first idea that comes to our minds is that we can focus on the adhesin in order to detach the biofilm from the surface whenever we want it to be disperses, or give it to the bacteria from an inducible promoter to control the adhesion. However, this adhesin is a really huge protein that has got several kilobases in the genome, and the genetic manipulation of it would be very difficult to achieve. Therefore, we decided to manipulate the proteins needed to export the adhesin and degrade it.

LapG is a periplasmic protease that participates in the biofilm dispersion process by cleaving adhesion proteins such as LapA. LapC is an essential protein for the secretion of adhesion proteins (such as LapA) that are involved in the biofilm formation process. The creation of a lapC- mutant avoids the secretion of these molecules, hence blocking biofilm formation. We created a double mutant lapC-lapG-, in which one of the proteins needed for the export of the adhesin does not exist (LapC), neither the protease needed to degrade the adhesin, LapG. This bacterium is not able to form a biofilm, but if we provide a functional lapC gene, the accumulated adhesion LapA will be able to go out and the bacteria will be able to produce the biofilm. Whereas if we do not provide the transporter and we provide the protease, the adhesion will be cleaved and the bacteria will disperse the biofilm.

This allows to introduce genes for both the formation and the dispersion of biofilm under the control of an expression system that responds to a desired regulation.

However, this will not be enough to ensure a non-dispersal biofilm, and definitely it will not ensure that the biofilm that is formed will be more robust and grow faster or higher than a regular biofilm, which is our main goal in order to obtain a strong and regulated biofilm for bioremediation purposes. Besides, the dispersal could not be entirely satisfactory, as there exists a protein whose function is to retain LapG and prevent the proteolysis of the union of the adhesin.

For these reasons, we decided to combine this control system with another one that regulated the biofilm in a metabolically level. For this, we decided to manipulate the levels of cyclic diguanilate monophosphate (c-diGMP). As we can see in the scheme, this molecule can regulate both the formation and dispersion of the biofilm, depending on the quantity of it that is present inside the cell. High levels of c-diGMP will increase the biofilm formation, and low levels of it will induce its dispersion. To manipulate this, we will make use of a phosphodiesterase (PDE), that will destroy the c-diGMP, and a diguanilate cyclase (DGC), that will produce it, YhjH and PleD* respectively.

These four genes, lapC, lapG, yhjH, and pleD*, allow us to control the formation and dispersion of the biofilm, to enhance it and make it stronger, and to be able to induce it whenever we want to. Once we have that, we can improve the glycerol bioremediation!

Why glycerol?

Glycerol is an alcohol of three carbon atoms, which is part of biomolecules such as phospholipids or triglycerides, and is also an important intermediate compound for the cell metabolism. It can be obtained from both living beings and chemical synthesis. Among others, its main uses are as a food sweetener and it is also an important ingredient of cosmetic and pharmaceutical products.

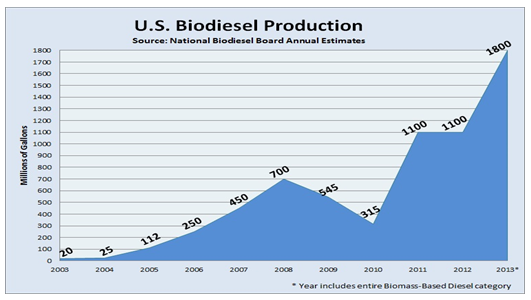

In spite of its numerous uses, in the last years glycerol production has greatly exceded its demand. The industry of biodiesel, which is becoming a really popular energy source, produces about a 10% of glycerol as a byproduct. This increase in the glycerol generation has led to a fall in prices and its accumulation (Figure 2). It is therefore urgent to find another way to use this product, so the excess of glycerol is removed from the environment and used in other industries.

Some of the current options are its use in animal feeding or as a solvent for chemical and enzymatic reactions. It can also be used as a source of carbon and energy in microbial cultures that produce useful compounds such as carotenoids, lipids, bioplastics like polyhydroxyalcanoate, or even hydrogen. In this field, synthetic biology would allow to generate bacterial strains which are able to consume glycerol and produce some of these compounds.

Figure 2. Increase in the biodiesel production, which leads to glycerol accumulation.

Because of this, we thought that it may be a good idea to feed our bacteria with glycerol. Pseudomonas putida is a GRAS (Genetically Regarded As Safe) organism, what means that it is completely safe, even for its release to the environment. If we could find the way to increase its consumption of glycerol, we will be ending with a huge problem of environmental pollution, as well as feed our production system.

For this end, we have produced a P. putida strain that has a knock-in with gene glpF. This bacterium already has all the genes needed for the assimilation of glycerol, but they are repressed in the absence of this molecule. By cloning glpF under the control of another promoter, this problem can be easily solved. This gene is an aquaporine that specifically helps to the entrance of glycerol inside the cell, as we can see in the Figure 3.

Figure 3. Metabolic pathway of the glycerol uptake and incorporation in the central metabolism. OprB and GlpF are glycerol transporters for the outer and inner membranes, respectively. GlpK and GlpD are involved in the conversion of glycerol into molecules of the central metabolism.

Production module

Once our bacterium can eat and use glycerol, the carbon and energy obtained from this source can be used to produce a wide range of compunds, such as plastics, propanediol, citric acid, propionate, or butanol. Thanks to our modular system and the biobrick format, the genes for different metabolic pathways can be inserted in our biofilm-forming, glycerol-eating bacterium, in order to be able to produce any compound of interest.

Propionate is the salt of propionic acid, which consists of three carbon atoms with a carboxylic group. It is widely used as a human and animal food preservative, as an intermediate in the production of plastics, pesticides and textiles, and also in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries.

It is present in the cells as propionyl-CoA, which is a product of the fatty acids beta-oxidation, and enters the central metabolism by being converted to succinate. Propionate itself is only common in some bacterial groups such as Propionibacterium, which get energy from the propionic fermentation process. This type of fermentation uses an anaerobic pathway using the inverse reactions of the Krebs cycle, and produces propionate from the central metabolism.

Currently, propionate is produced by chemical synthesis. However, its small size and simplicity makes it a compunds really easy to produce in bioremediation processes. The carbon which is consumed by glycerol-eating bacteria could be use to produce it.

Why did we choose propionate?

First of all, it is a small molecule and it is easily secreted by P. putida. Secondly, there are genes and metabolic pathways available in nature in order to modify our bacterial strain to be able to produce it. By means of molecular biology and synthetic biology, we can take genes for propionate production and insert them in the bacterium, under a regulatory and expression system. Finally, the demand of propionate is rising every year, therefore the biotechnological production of it would be an interesting option.

However, this is only an example of what our production system could do, as it has a modular concept in which some of the parts can be exchanged.

The following figure shows the genes that are necessary in order to produce propionate from the central metabolism:

Figure 4. Metabolic pathway for the conversion of succinate to propionate. ScpABC and Epimerase are the proteins which we will be using for our artificial pathway.

We have designed an artificial way, which can be seen in the next figure. This artificial pathway allows the return to succinyl-CoA, the first and last molecule of the route, with the consumption of succinate to produce propionate. This series of genes will be constructed as an operon, in which we will find the epimerase, scpA, scpB and scpC. These four genes will be the responsible for the construction of the pathway.

Figure 6. Artificial pathway for propionate generation. The scpABC genes are obtained from an E. coli K12 operon, while the epimerase gene is obtained from Pseudomonas mosselii.

How are these modules combined?

As our final objective is to obtain an industrial strain that had all the abilities given by the different constructs, each of the constructs of this project needs to be expressed in a regulated manner, as it will be necessary to stablish a fine control. In this way, we are going to put the biofilm genes under the control of a flip-flop system, in order to induce biofilm when we have enough biomass in the reactor, and disperse it at the end of the production cycle. This flip-flop system is the same used five years ago by the team of our University, in which we have a first part that is induced by IPTG and a second one that is induced by an increase in the temperature. This decision was made in order to have appropriate growing conditions.

The glycerol genes will be under a constitutive promoter, as the objective is to remove the maximum amount of glycerol we are able to. These constructions will be introduced in the genome of the bacteria by means of a miniTn7 device, a mini transposon that locates itself always in the same part of the genome, and that does not affect to the living conditions of the bacteria.

The propionate genes will be under de control of an expression system inducible by salicylate. This system is part of a cascade, that will highly increase the production of the different genes of the operon, allowing a huge production of the product we desire to obtain. In addition, as the system is inducible by an external signal, it will be easy to control the precise moment of the production, so the bacteria are not induced to produce when the biomass is still too low or they are not forming a biofilm.

Thanks to the biobrick format, this project is modular, and different genes can be exchanged in order to consume or produce a wide variety of products, taking advantage of the biofilm properties.