2016 PROJECT

Tripartite split-GFP and FRB*/FKBP12 dimerization system characterization

Characterization of our visualization tool was a two-step process. First, we needed to characterize the tripartite split-GFP activity, and then characterize the whole tool. You can find more details about this on our

strategy page.

We designed an experiment to characterize both the tripartite split-GFP and the FRB*/FKBP12 dimerization system. This experimental strategy would also allow us to validate the use of the FRB*/FKBP12 dimerization system to build our Bring DNA Closer (BDC) tool. To achieve this goal, we constructed two new biobricks: one composed of a sequence encoding FRB* linked to GFP11 and one composed of a sequence encoding FKBP12 linked to GFP10.

gBlocks

The following gBlocks were designed to be assembled with the GFP10 and GFP11 parts as it is illustrated in the strategy page of our wiki (Table 1).

Table 1: gBlocks used for the characterization of Tripartite GFP and FRB*/FKBP12 system.

| gBlocks

|

size (bp)

|

| gblock FRB

|

374

|

| gblock FKBP

|

419

|

We decided to order gBlocks of optimized FRB* and FKBP sequence instead of optimizing the FRB and FKBP coding sequences we got from Takara Clontech (* shows the optimization that we perform on FRB sequence to be more adaptable to bacteria system).This decision was only taken for time-saving considerations. We assumed that direct mutations for optimizing the coding sequence of FRB and FKBP and eliminating forbidden site were time-consuming steps.

To start we inserted each gBlocks in the intermediate plasmid and then extracted the plasmid coding for our gBlocks. Then by PCR amplification we obtained our desired sequences and with the assembly techniques such as ligation and Gibson we assembled different gBlocks together. We successfully constructed the plasmid containing our Biobrick coding for FRB-GFP11 (illustrated on [fig. 1]) and FKBP-GFP10 (illustrated on [fig. 2]).

Figure 1: Map of the plasmid pSB1C3 coding for FRB fused with GFP11

Figure 2: Map of the plasmid pSB1C3 coding for FKBP fused with GFP10

We then assembled both plasmids together and constructed the plasmid coding for FKBP-GFP10 and FRB-GFP11 as shown in [fig. 3].

Figure 3: Map of the plasmid pSB1C3 coding for FKBP-GFP10 and FRB-GFP11

We test the expression and integrity of the three compounds of the system with a western blot. But we could not obtain polyclonal anti-GFP so we used a monoclonal one. As we were afraid monoclonal antibody recognize only one subunit of the tripartite GFP, GFP1.9. So there is a lack of information, we know that GFP1.9 is well expressed but the GFP10 and GFP11 negative result didn’t allow us to know if there are not expressed as the monoclonal anti-GFP antibody epitope seems to be on GFP1.9.

Figure 4: Expression of GFP1.9 validated by western blot with monoclonal anti-GFP antibody

On this western blot control GFP appears between 28 and 38 kDa. GFP1.9 subunit is also revealed with a lower weight as expected. But GFP10 and GFP11 are negative.

Test of the dimerization system and tripartite GFP

We transformed E.coli with pSB1C3 coding for FKBP-GFP10 and FRB-GFP11 and pUC19 coding for the third part of GFP as we could not clone GFP1.9 in pSB1C3. Transformed cells where then incubated with the dimerization agent, rapalog. We try several concentration of rapalog but we did not see any GFP fluorescence with flow cytometer.

Figure 5: : No GFP florescence is observe with rapalog

All the rapalog concentrations tested (5nM, 50nM, 500nM) display a signal inferior compared to the negative control.

We did not obtain the fluorescent signal that we expected with the dimerization agent. We did not have time to investigate further why the system did not work, but we have several ideas. We may have some expression issues with FRB*-GFP11 and FKBP-GFP10 as the western blot done with monoclonal antibody anti-GFP allow the revelation of GFP1.9 only. Another possibility is that there is some physical constraint that prevent GFP assembly, the linker length for example can generate this kind of constraint. Finally, the system can by well-constructed and expressed but we may not have found the optimal conditions to induce the dimerization (concentration of rapalog, timing, temperature).

Visualization tool characterization

In order to characterize our visualization tool, we designed a plasmid (pZA11) in which there are two target sites for dCas9 proteins fused with GFP parts. By this mean we are able to determine the optimum distance between the two dCas9s target site for GFP fluorescence. Details about this experiment are mentioned in our strategy page. Furthermore, a model was made by bioinformatics tools to estimate the optimum distance between the two dCas9s.

Table 2: List and size of gBlocks ordered to build the characterization plasmid and the sgRNA expression system.

| gBlocks

|

size (bp)

|

| gblock detection

|

1020

|

| gblock St sgRNA

|

310

|

| gblock Nm sgRNA

|

362

|

| gblock spacer

|

900

|

We successfully inserted all the gBlocks into intermediate plasmids. However, due to a lack of time, we could not achieve the final construction of our plasmid (pZA11) by Gibson assembly method.

Construction of the two different systems

Bring DNA Closer (BDC) tool construction

The BDC tool construct is composed of the dCas9 Sp linked to FRB* and the dCas9 Td linked to FKBP12 (for further details, check our Design page. To build this tool, [http://www.addgene.org/48657/ dCas9 Sp] and [http://www.addgene.org/48660/ dCas9 Td] were ordered from addgene.org, and the genes encoding the optimized FRB and FKBP12 were obtained by ordering gBlocks from [http://eu.idtdna.com/site IDT] [Table 1].

As plasmids we received from addgene.orgwere already transformed into the bacteria, we prepared the overnight culture of received bacteria in order to extract the plasmid coding for dCas9. In this part of the project, we faced some difficulties because the plasmids were low copy number. We used a midi-prep kit in order to extract enough plasmids. However, according to the results of PCRs on the extracted plasmids, we could not amplify the coding gene of the dCas9s. Furthermore, we sent plasmids for sequencing. We found out that the 3’ end of the gene encoding dCas9 Td did not match the expected sequence.

Due to a lack of time, we decided to put aside the BDC tool construction to focus on constructing the visualization tool as it was mandatory to have it first in order to use it to validate our BDC tool.

Visualization tool construction

Experimental design

For this sub-project, we ordered gBlocks thanks to IDT’s offer, and according to our design. Since these gBlocks are used to build our biobricks, they had to respect iGEM's and IDT's requirements. Therefore, the sequences we designed were modified to remove forbidden restriction sites, adapted to E.coli codon usage, and have an acceptable GC% and number of repetitions within the sequences. Each of these gBlocks were integrated into intermediate plasmids (pUC19 or pJET) and those plasmids were transformed into E. coli. Then they were sent for sequencing to check whether the inserted gBlock had the right sequence. When the gBlocks have been validated, they were ready for further manipulation such as Gibson assembly or digestion and ligation techniques to construct our final design.

The following gBlocks were designed to construct our Visualization tool [Table 3]:

| gBlocks

|

size (bp)

|

| gblock 1.1

|

960

|

| gblock 1.2

|

960

|

| gblock 2.1

|

1023

|

| gblock 2.2

|

808

|

| gblock 3.1

|

960

|

| gblock 3.2

|

960

|

| gblock 4.1

|

706

|

| gblock 4.2

|

1288

|

| gblock GFP 1.9

|

862

|

Table 3: gBlocks used to build the visualisation tool

Figure 6: Scheme of the visualization tool design. Visualization tool is composed of three main parts: the biobrick containing dCas9 NM linked to GFP10 coding sequences, the biobrick containing dCas9 ST linked to GFP11 coding sequences, and the biobrick containing the GFP 1-9 coding sequence. The two first biobricks are split into 2 fragments, themselves split into 2 gBlocks.

As it is described in [Fig. 4], the biobrick containing the coding sequences for dCas9 NM linked to GFP10 is composed of two fragments called fragment 1 and fragment 2. These two fragments are themselves respectively composed by the ligation of gBlocks 1.1 and 1.2, and gBlocks 2.1 and 2.2. The biobrick containing the coding sequences for dCas9 ST linked to GFP11 is composed of two fragments called fragment 3 and fragment 4. These two fragments are themselves respectively composed by gBlocks 3.1 and 3.2, and gBlocks 4.1 and 4.2. It is important to note that in both biobricks, the two fragments are overlapping to allow an assembly by the Gibson method. Finally, the third GFP subunit (1 – 9) biobrick is only composed of the gBlock GFP 1-9.

Checking gBlocks sequences

The first step was to check gBlocks, because according to IDT, 80% of the gBlocks have the correct ordered sequence. In order to check them, gBlocks were cloned into pUC19 in first attempt, or pJET plasmid for difficult cases. pUC19 is a plasmid that allows white/blue screening, and pJET is a plasmid that allows only cells containing the plasmid cloned with an insert to grow on selective media. Positive colonies were screened by colony PCR, using the universal pUC19 or pJET vectors. PCR products were checked using gel electrophoresis. [Fig. 5] shows the results for gBlock 3.1. In this particular case, the expected fragment was 960bp. Results showed that clones 2 and 5 were positive. Plasmid DNA selected by PCR colony screening were cultivated then extracted to be sent for sequencing.

Figure 7: Colony PCR products gel electrophoresis of gBlock 3.1. Expected fragment: 960bp. Clones 2 and 5 are positive.

Assembling the gBlocks to get the desired biobricks

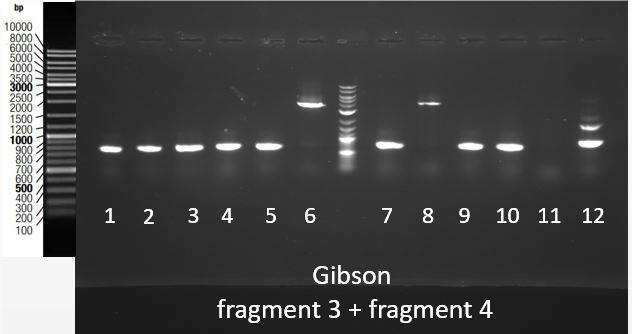

When sequences were as expected, the same plasmidic DNA extraction products were used to perform high fidelity PCRs, using primers which hybridized at both extremities of the gBlock. These PCR products were then stocked or used to perform ligations, and the ligation products were amplified by high fidelity PCRs. [Fig. 6] shows the electrophoresis gel of PCR amplifications of ligations made in order to obtain fragments 3 and 4. The expected fragments size are respectively 1920bp and 1994 bp.

Figure 8: Gel electrophoresis of ligation products amplified by high fidelity PCR for fragments 3 and 4. Expected size were respectively 1920 and 1994 bp. Results showed that fragments with the correct size were obtained.

Thanks to an overlap between the two fragments (1 and 2, 3 and 4), an overlap between the prefix present at the beginning of fragment 1 and 3 and pSB1C3, and an overlap between the suffix present at the end of fragment 2 and 4 and pSB1C3, we were able to assemble them in pSB1C3 using the Gibson Assembly method. Gibson Assembly products are then transformed into bacteria, and a colony PCR was performed using primers complementary to the suffix and prefix sequences to screen positive bacteria colonies. PCR products are then checked on gel electrophoresis. [Fig. 7] shows the results of this screening for the assembly of fragments 3 and 4 in pSB1C3. The expected band size is approximately 4000 bp. This fragment was obtained for colonies 6 and 8.

Figure 9: Migration of colony PCR products obtained from bacteria transformed with the Gibson Assembly of Fragments 3 and 4 in pSB1C3. The expected product was around 4000 bp and it was found at the expected size for clones 6 and 8.

Therefore, plasmids were extracted from the cultures of colonies 6 and 8, and were then stocked and sent for sequencing. The sequence was as expected except for the joining of gblocks 3.1-3.2 and 4.1-4.2 where one nucleotide was missing.

Summary of the visualization tool construction

Concerning the sequence encoding the dcas9 ST linked to GFP11, the ligation between the gBlocks 2.1 and 2.2 did not seem to work as we could not amplify fragment 2 by doing a PCR on the ligation product of fragments 2.1 with 2.2. The third part of the tripartite GFP (GFP1-9) was obtained in the pUC19 plasmid with the expected sequence but its cloning into the pSB1C3 plasmid by digestion/ligation was unsuccessful.

To sum-up, we were able to construct the biobrick containing the dCas9 ST linked to GFP11 (but with two missing nucleotides) and also the biobrick containing coding sequence for the third part of tripartite GFP (GFP 1-9) but only in the pUC19 plasmid. We did not obtained the construct of the dCas9 NM linked to GFP10. Consequently, we did not get a full construct of our visualization tool and thus we were not able to test it.

2014 PROJECT

Improvement of a previous part, BBa_K13372001

As a part of the characterization of a previous existing Biobrick Part, we have chosen the [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K1372001 BBa_K13372001] biobrick from the Paris-Saclay 2014 project This is not a lemon. It was designed to mimic the ripening of a lemon in E. coli by a salycilate-inducible expression of a suppressor tRNA.

The Paris Saclay 2014 team chose to use chromoproteins to express these colours in E. coli. Chromoproteins are reflective proteins that contain a pigmented prosthetic group and do not need to be excited to be seen. They fused a yellow chromoprotein with a blue one in order to display a green color. This construction is referred as the green fusion chromoprotein. In order to make the bacteria ripe like a real lemon, they decided to take advantage of the fusion protein’s design by using a translational suppression system. They added an amber codon (stop codon) within the linker separating the yellow and the blue chromoproteins genes. Therefore, the suppressor tRNA will suppress amber codon allowing the translation of the green fusion chromoprotein in presence of salicylate. Conversely, the down regulation of the suppressor tRNA in absence of salicylate will allow bacteria switch from green to yellow, thus simulating the ripening of a real lemon. This system is referred to as the colour switch system [Fig. 8].

Figure 10: Schema of the lemon ripening project. The decrease of salicylate concentration causes a lost of suppressor tRNA and so on the fall of blue chromoprotein expression : bacteria changes from green to yellow.

The tRNA used is the supD suppressor tRNA. It has been placed under control of a salicylate inducible promoter Psal. Its role is to suppress the introduced amber codon. The nahR gene encodes a transcriptional regulator that is induced by salicylate and thus binds nah or Psal promoters. In presence of high salicylate concentration in the agar media, supD will be expressed and so the green fusion chromoprotein: bacteria will display a green color. However, as bacteria grow into agar, less salicylate will remain available into the media. Thus, the decrease of the nahR-salicylate complex amount within bacteria will lead to supD downregulation through time. In turn, decrease of supD amount will result in less codon readthrough and so less translation of the green fusion protein and more translation of the yellow chromoprotein. As a result, bacteria will gradually change from green to yellow [Fig. 9].

Figure 11: Explanatory diagram of the lemon ripening. NahR becomes active in presence of salicylate : there is expression of suppressor tRNA. This one suppresses amber codon allowing the translation of the green fusion chromoprotein.

Characterization

In order to characterize the biobrick, the color switch system (BBa_K13372001) was tested on three different constructions, contained in the plasmid pcl99:

- TAA: LacZ and Luc coding sequences in the same open reading frame, separated with an ochre stop codon.

- TQ: LacZ and Luc coding sequences in the same open reading frame.

- TAG: LacZ and Luc coding sequences in the same open reading frame, separated with an amber stop codon.

Each condition was tested under three different salicylate concentrations. In order to achieve that, both measurements of Beta-Galactosidase and Luciferase activities were performed on bacteria cultures [Fig. 10].

The experiment was conducted on three sets of cultures of bacteria:

- TAA: BL21|pSB1C3_BBa_K1372001 and pcl_TAA

- TQ: BL21|pSB1C3_BBa_K1372001 and pcl_Tq

- TAG: BL21|pSB1C3_BBa_K1372001 and pcl_TAG

Each of those sets of culture were incubated with three different salicylate concentrations: 0, 30µM and 1mM.

Three clones (clones 1, 2 or 3) were tested for each condition, with three different salicylate concentrations (0, 30µM or 1mM), with in addition a negative control sample.

pcl_TAA construction contains a TAA stop codon between LacZ and Luc. This codon is not recognized by the supD suppressor t-RNA : no luciferase activity is expected.

pcl_Tq construction does not contain any stop codon : the luciferase activity is expected to be at the maximal.

pcl_TAG contains the TAG codon recognized by supD suppressor t-RNA : the expression of luciferase should be inducible by salicylate.

Figure 12: Explanatory diagram of the characterization. pcl_TAA construction contains a TAA stop codon between LacZ and Luc. pcl_Tq construction does not contain any stop codon. pcl_TAG contains the TAG codon recognized by supD suppressor t-RNA.

The luciferase luminescence is expected to vary depending to the different constructions conditions and to salicylate concentrations, instead of the Beta Galactosidase activity, which will remain constant. Thus luciferase data were normalized with those from Beta Galactosidase and our results are expressed as the Luciferase/Beta-Galactosidase activity. This ratio is independent of the level of transcription, initiation or mRNA stability.

Figure 13: Luciferase activity with TQ construction depending of salicylate concentration. 3 clones were tested per condition. Luciferase activity depends on the transcription of pclTAA.

The Tq plasmid does not contain any stop codon between LacZ and Luc. Thus, no matter the salicylate concentration, both Luciferase and Beta Galactosidase activities are supposed to be detected.

As expected a high level of Luciferase/bGal activity is observed, but the ratio decreases when salicylate concentration increases [Fig. 11]. Indeed, both activities of Luciferase and bGal drop from 30µM of salicylate, but luciferase activity was more affected by the salicylate than bGal one.

One may hypothesize that salicylate inhibits differently both reporter proteins activities, with a stronger inhibition of luciferase activity. We cannot determine whether this inhibition is due to a physiological consequence onto bacteria metabolism or occures after protein extraction.

In order to read the next results, we calculated a readthrough percentage, by doing a ratio between luciferase/bGal from TAA or TAG constructs and luciferase/bGal from TQ. Thus, we obtain a readthrough percentage.

Figure 14: Luciferase activity with TAA construction depending of salicylate concentration. 3 clones were tested per condition. Luciferase activity depends on the expression and capacity of the suppressor t-RNA to read TAA codon.

In TAA condition, regardless of the salicylate concentration, there is no significant Luciferase activity, so the ratio remains very low at any concentrations [Fig. 12].

We conclude that supD suppressor tRNA is very specific of the TAG codon and has no impact on the TAA stop codon.

Figure 15: Luciferase activity with TAG construction depending of salicylate concentration. 3 clones were tested per condition. Luciferase activity depends on the expression and capacity of the suppressor t-RNA to read TAG codon.

In TAG condition we can see an increase of stop codon readthrough activity with the increase of the salicylate concentration [Fig. 13].

In comparison to the results obtained with the TAA construction, the readthrough level increases similarly to the concentration of salicylate.

This indicates that TAG stop codon is efficiently readthrough in presence of supD tRNA, allowing the production of a significant amount of luciferase.

In conclusion, the Psal promoter is fully inducible by salicylate and the suppressor tRNA is functional to suppress the TAG codon. These experiments demonstrate that the BBa_K1372001 biobrick is fully functional.