Overview

Synthetic biology isn’t easy to explain to non-scientists. But explaining CRISPR-Cas9 is way harder. Not only because those matters are complex, but also because we still don’t know precisely the consequences of such technologies. If CRISPR-Cas 9 is undoubtedly a revolution, the seism affects other fields, interconnected with science (ethics or law as an example).

As our project use CRISPR-Cas9 we looked for its potential huge consequences. It seemed important for us to collect the opinion of both scientists and non scientists. As we worked on CRISPR-Cas9, we discovered how overwhelming it could be, and ask ourselves how we could imagine a responsible way to work with this technology.

Thus, we tried to find an answer in the concept of responsible research and innovation (RRI). We believe that this concept could help iGEM teams to think about responsability in their project. Considering our project on CRISPR-Cas9, we believed the concept could give us the good questions we should ask ourselves to build a responsible project.

This lead us to investigate about CRISPR-Cas9 and its major consequences in several fields. We tried to draw the consequences and think about what would be a responsible use for scientists but also considering the societal issues. Our Human Practices followed two goals : researching among stakeholders what would be a responsible use, and popularising science for public.

As there is no general responsible rules than can be applied to all project we developed a RRI test : this test works as a feed-back for each iGEM projects, in order to improve the responsability in the long term.

A feed-back on the responsability in a project on CRISPR-Cas9 can give a personal experience about the problematics the project met, and a quick overview on how we could deal with them.

See the RRI test : Media:T--Paris_Saclay--RRI_Test5.pdf

The societal issues of CRISPR/Cas9

Guided by curiosity we tried to establish a public dialogue beyond the lab on the societal issues of CRISPR/Cas9. We met public and stakeholders and tried to combine their contributions.

What we wanted was the ability for everyone to express an opinion on science. Everyone should be able to question Synthetic Biology, professional or simple citizen. This is even more true with CRISPR/Cas9. The ethical question behind is so big every citizen should be involved.

We tried to gather all of the opinion on the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9, from different fields, but also from public and professionals.

Our concern about Public Engagement is so strong we made "Inclusiveness" as one of the principles of our Responsible Research and Innovation Test. To learn more about it, SEE HERE METTRE LIEN. When we asked to 17 teams to fill this test we saw how much inclusiveness is important among iGEM teams.

Firstly, we tried to have a great outreach, then we learned a lot on CRISPR/Cas9 by meeting politics, scientists or patent Attorneys. At last, we connected public and stakeholders during a conference on the societal issues of CRISPR/Cas9.

Outreach

Synthetic Biology Survey

In a first step, in order to build a better outreach, we wanted to know how much people knew about synthetic biology. We made a survey and spread it as much as possible.

We know survey are not always the best reflection of the reality. In a vision of righteousness and honesty we looked for the weaknesses of our results in order to have the best interpretation of it. Here are some rules we should keep in mind about this results:

· We tried to have answer of both scientists and non-scientists in reasonable proportion, in order to have a truest vision of the reality. If we didn’t pay attention we knew most of the people who would have answered would be people close to us, and most of them are scientists.

· This survey has been spread on social networks. Most of the people who answered to it are French young people (79% of the people are between 20 and 30 years old).

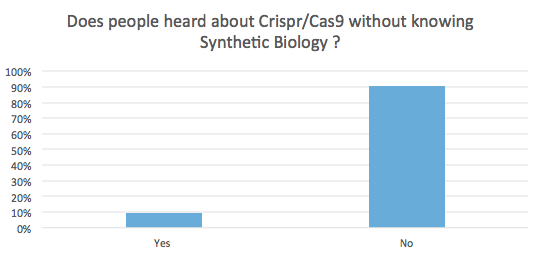

Some questions interested us. We knew from previous experiences that synthetic biology is not well-known among public. A lot of medias talked about CRISPR-Cas9. We wanted to know if people without scientific background knew more CRISPR-Cas9 than synthetic biology. We guess we could see the influence of medias on scientific knowledge.

The survey showed us clearly that the influence of the media was not so important: only 10% of the people had heard about CRISPR-Cas9 without knowing synthetic biology.

The main factor of knowledge of synthetic biology and Crispr-Cas9 seems to be the scientific educational background.

Ethics: We also wanted to know how a scientific formation could impact the perception of CRISPR-Cas9. We thought people without scientific background would probably have more fears than people which have a scientific formation. Here again our expectations have been challenged: 3% of the people without scientific background strongly fear CRISPR-Cas9, while 9% of people with scientific background strongly fear it… 66% of the people without scientific background and 60% of people with scientific background think CRISPR-Cas9 could lead to new treatments.

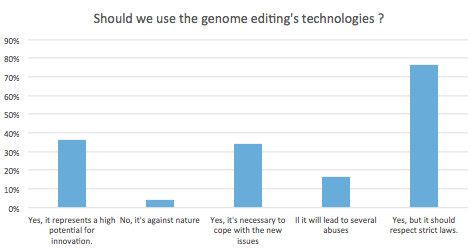

The results are very low and quite similar: the perception of CRISPR-Cas9 does not evolve that much, if you have a scientific background or not. People fear CRISPR-Cas9 but as they know it could be beneficial for society they are in favor of it. Nonetheless, the bulk of the people we asked (76%) think editing genome is good but should respect strict laws.

Festival Vivant

The “Festival Vivant” is a three days festival, to debate and share views about living organisms and the way we use them. During these three days you could find conferences, workshops and meetings. The iGEM Paris Saclay’s team was there to present the field of synthetic biology and our iJ’AIME project. This festival presented different insights about living organisms to professionals, students and general audience. This festival gave us an other opportunity to do popular science. On this occasion we worked on popularising science : we modeled our project, and presented posters about it.

Exhibitions

The iGEM Paris Saclay 2016 team made an exhibition in Nanterre’s University, a french university that is mostly non-scientific. We made posters, explained to students what was synthetic biology. It was a successful exhibition because the discussion we had with students were very different from discussion from scientific or general audiences !

Vox Pop

Our team made a vox pop in a park in Paris, “Les jardins du Luxembourg”. We wanted to know if people ever heard of the field of synthetic biology, and if not spread the field and get their opinion on the subject.

What did we learn of this experiments ? Most of the people we met trust scientist to be responsible in their use, and doesn’t feel legitimate to bring a critic on a subject they don’t master.

File:T--Paris Saclay--Vox Pop.mp4

Meeting stakeholders

In order to know more about the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9 we went to met stakeholders from different fields around science and law.

Meeting with Agnès Ricroch, a professor at AgroParisTech school working on plants and their regulations

She brought an interesting opinion : CRISPR-Cas is not a revolution, but a continuity. In fact, everything CRISPR is able to do already existed (like cutting the genome). CRISPR is neither easier to use : we still need to do a transgenesis in order to do it, and not everybody has the tools to do it.

On regulations Mrs Ricroch casted a light on the non-coherence of the system. A lot of different regulations coexists, for GMO’s or plants for instance. However, sometimes, those different regulations apply to the same object : how can we guess if an organism underwent genetic mutations ? Oftenly, those mutations cannot be seen on the final results. The law needs to be updated on the technologies, to be able to seize all of the evolutions.

When we talk about CRISPR-Cas9, we immediately think about ethics and abuses. Mrs Ricroch had a strong concern on putting first the great challenges facing humanity. Among these challenges, some of them can be solved by science. She told us we had to weigh the pros and the cons. But we should always remember first the issues we would be able to solve with science.

Meeting with Marc Fellous, Emeritus Professor at Paris Diderot University and Medical Doctor

He told us CRISPR technique is a revolution because it eases genome editing which obviously raised new issues. It is, thus, necessary to established rules. Today, CRISPR has a wide range of applications: plants, animals, insects. CRISPR is interesting today in the struggle with Zika virus transmitted by mosquitoes. Some researcher looks at the question by modifying genetically female to render them sterile thereby erasing any progeny.

When it comes to the question: Does this technique should be applied to humans? Well, there is a general consensus among the scientific community, the answer is no, not if it affects the human progeny.

To sum up, CRISPR is a more precise gene editing technique which ease the process and reduce the risk of “off-target”.

== Meeting with Eric Enderlin: The Legal vision

French and European Patent Attorney at Novagraaf ==

Legally speaking, CRISPR does not raise any issue, patent law is the law of innovation. Research and legal protection can work together. The problem comes from a misguided perception: patentability provides a return on investment which allows then to fund future researches. The example is clear when it comes to fund research for rare diseases. In those cases, where public fund is difficult to obtain because the number of patients is small, patentability offers a solution.

Patent law is not there to restrain scientists in their work, indeed, 80% of the scientific information is contained in those patents. As a consequence, Patent law must be seen more as a source of economic development and a source of information.

In France, the tradition for scientist is to published their results for the recognition from their peers. This tradition destroys the requirement of novelty necessary to patent any invention. Thus, in France even if the country has the first place for innovation, there is a lack of valorization and protection

Last step : connect public and stakeholders

If we met public and stakeholders to improve our research on the societal issues of CRISPR/Cas9 we also connected the two. This connection happened during a conference we made about the societal issues of CRISPR/Cas9.

Conference: the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9

French poster of the conference on the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9

Because we had a strong concern both on popular science and meeting stakeholders, we hold a conference in our university, in front of students, with two researchers, Jean Denis Faure, a researcher and teacher at AgroParisTech school using CRISPR-Cas9 on plants, and Pierre Walrafen an European patent attorney.

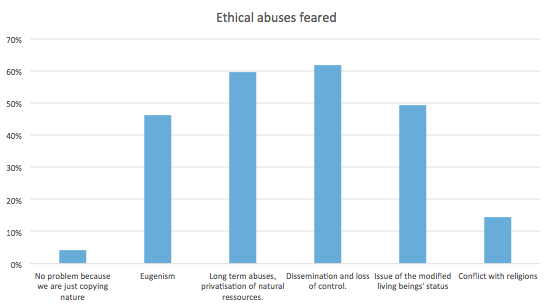

We tried with our guests to think about the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9, for the ethics, the law and the economy. The ethical problems CRISPR-Cas9 is bringing are huge, and for most of them, unknown. The ethical problems comes with what is done with the technology : therapeutical applications ex vivo or for genetical diseases, or applications on embryos and germ cells. The ethical problems comes along with the question of transhumanism. The issues are rising because of the simplicity of CRISPR-Cas9, authorizing a wider scientific audience to edit the genome.

About the legal framework, our speakers made a comparison between the European legal framework, the process based evaluation, and the product based evaluation, and how the patentability was in Europe restrained by a principle of public order. To learn more about GMO regulation, click here.

Responsible Research and Innovation : Bring innovation and societal need closer

We chose to work on human practices directly linked with our project : because we were working with CRISPR-Cas9, we tried to know more about it and to learn how to use it in a responsible way. We wanted this research to have a direct effect on our project. Innovation often try to answer a societal need. However this societal need is not always reached, because the innovation is not fit for the users, because it has deep negative impacts that have not been seen, because the project was not well defined in a first time...Sometimes the project missed its goals, because the desire to meet it was not followed by strong principles. We tried to have the strongest connection between innovation and societal need. In other words, we tried to bring innovation and societal need closer.

Our work to bring them closer was possible thanks to Responsible Research and Innovation principles. Responsible Research and Innovation is a nascent governance concept that aims to guide research towards societal goals. Those principles have been developed by the European Commission. Responsible Research and Innovation works as soft law : it is not meant to substitute to written law (hard law) but to complete it. Soft law like RRI has the advantage of quick adaptability, when written law is often late because it can't change as fast as science. Thus, we believe RRI is a good framework for the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in our research, because written law did not already ruled on this brand new technology.

While working on the concept of Responsible Research and Innovation we had the idea to create a RRI Test, which works as a feed-back for the projects. The principles of Responsible Research and Innovation guided our research, and the RRI test helped us to reshape it to build a more responsible project.

We thus integrated all our human practices on CRISPR-Cas9 by the bias of responsibility : the RRI worked as a tool to integrate our human practices in our project. Indeed, this tool helped us to have a better decision making, more rational and guided towards societal needs.

We filled our test to see how we responded to the principles we wanted to follow. This test is divided in four parts : Reflexivity, Anticipation, Inclusiveness/Deliberation, Responsiveness.

We believe iGEM could be a great laboratory for this principles. Following this idea we gave the test to several teams. They all filled it and we tried to see how the four axis of RRI (Reflexivity, Anticipation, Inclusiveness, Responsiveness) are integrated by the teams. This four axis comes from the article Responsability and intellectual property in synthetic biology, Harald König, Pedro Dorado-Morales and Manuel Porcar.

The four axis of our reflexion on RRI :

- Reflexivity : The reflexivity leads the team to think about the choices that has been made, “the underlying purposes, motivation and potential impacts of the project”. The question of reflexivity happens in the first step of the project. Reflexivity tries to find how the team thought about the purpose of the innovation.

- Anticipation : Anticipation requires to describe and analyze possible impacts, and create the appropriate solutions and policies. Every scientific project includes impacts. Even though all the impacts can’t be predictable at the beginning of the project, a lot of them can be seen. This anticipation is scientific but also juridical (decide about the best legal framework).

- Inclusiveness : Inclusiveness and deliberation requires to listen to perspectives from publics and stakeholders. Inclusiveness requires to listen to stakeholders, but deals also with outreach and pluridisciplinarity.

- Responsiveness : Responsiveness is a good indicator for the efficiency of RRI in the project. Searching if the previous dimensions helped to shape the project toward the RRI’s goals.

What did we learn on our project ?

I/ Reflexivity

When we chose our project we had different options. We chose to take a fundamental project, riskier but more original.

Stakeholders were essential to help us build our project. They helped us to focus on many points and to put the project in perspective. We thus met many scientists, but also jurists and public.

Was our project needed ? We thought about the different applications of the project. It was not an easy task because the project is a fundamental one. We were guided by a publication of Olivier Espéli “From structure to function of bacterial chromosomes : evolutionary perspectives and ideas for new experiments”, which said a tool like ours would be useful for scientists (FEBS Letters, 2015). We find that our tool would be useful for biologists because of its simplicity, but also in health. This tool could indeed help to diagnose genetic diseases.

The impacts of our project were difficult to define, because it was a project of fundamental biology : even if we defined the potential applications of our project, other scientists or industrials can invent new ways to use our tool. We can't guess what would be the use of this new ways. But the impacts of a responsible project can’t be only transferred to the user and his use in a environnemental or health context ; science itself must be responsible.

With this reflexion came the main question the RRI test asked us : how RRI could apply to fundamental research, such as our project on CRISPR-Cas9 ? The societal goal doesn’t seem to exist. However, building a responsible research is in itself a societal goal : having a more responsible science is undoubtedly a benefit for the society. The stakeholders of a fundamental project are the ones whose voices are interesting and necessary on science. In other words, the stakeholders are less identified. On our focus on CRISPR-Cas9 we felt necessary to gather stakeholders and tried to draw with them the future of a responsible use on this technology.

II/ Anticipation

The more we knew about CRISPR-Cas9, the more we realised we didn’t know much on this technology and its impacts. The difficult anticipation in the scientific field transferred our questions on the human practice, and we try to learn from stakeholders what the burning issues can be on CRISPR-Cas9, and tried to get people know more about it.

III/ Inclusiveness/Deliberation

As our project was in the field of synthetic biology, we had a strong concern about inclusiveness. We met a lot of stakeholders and public. In our case of fundamental research we defined the stakeholders as scientists using CRISPR-Cas9 and counselors in industrial property.

POPULAR SCIENCE : A KEY CONCERN

As we believe popular science is a key concern in synthetic biology and especially for CRISPR-Cas9, we lead several activities in this field.

During a vox pop we saw that people were mostly unaware of synthetic biology itself. We thus tried to meet public, to discuss with us of synthetic biology, CRISPR and our project. (link of the vox pop ?)

We met students during an exposition in the Nanterre University, but also during the Festival Vivant, opened to everyone and an exposition at the Pays de Limours.

What did we learn of this experiments ? Most of the people we met trust scientist to be responsible in their use, and doesn’t feel legitimate to bring a critic on a subject they don’t master.

CONFERENCE : THE SOCIETAL ISSUES OF CRISPR-CAS9

Because we had a strong concern both on vulgarisation and meeting stakeholders, we hold a conference in our university, in front of students, with two researchers, Jean Denis Faure, a researcher and professor using CRISPR-Cas9 on plants, and Pierre Walrafen a scientific with a cellular biochemistry and patent engineer.

We tried with our guests to think about the societal issues of CRISPR-Cas9, for the ethics, the law and the economy. The ethical problems CRISPR-Cas9 is bringing are huge, and for most of them, unknown. The ethical problems comes with what is done with the technology : therapeutical applications ex vivo or for genetical diseases, or applications on embryos and germ cells. The ethical problems comes along with the question of transhumanism. The issues are rising because of the simplicity of CRISPR-Cas9, authorizing a wider scientific audience to edit the genome.

About the legal framework, our speakers made a comparison between the European legal framework, the process based evaluation, and the product based evaluation, and how the patentability was in Europe restrained by a principle of public order.

Meeting stakeholders

Because we think meeting stakeholders is really important to build our project we met several of them.

As we said before, we met the professor Olivier Espéli, who helped us to shape our project. We also met Mr. David BIKARD, a reseacher at the Institut Pasteur in Paris and an expert on CRISPR-Cas9 utilization. He helped us choosing which orthologous dCas9s to use for our project, in order to maintain the sgRNA/dCas9 recognition specificity.

On our Human Practices research, we met different stakeholders to think on this field.

We met Agnès Ricroch is a professor at AgroParisTech school working on plants and their regulations, the professor Marc Fellous, Emeritus Professor at Paris Diderot University and Medical Doctor, Eric Enderlin a French and European Patent Attorney at Novagraaf, Geneviève Fioraso, french deputy and former minister of Higher Education and research, and Catherine Procaccia, French Senator working on a report on the economical and environnemental issues of new biotechnologies.

You can learn more about this interview here : METTRE UN LIEN vers les interviews

This meetings helped us to define and shape our project, but also to think about the tool we were working on. We tried to meet stakeholders from the different fields involved (scientific, legal, politics), in order to have the broader view on CRISPR-Cas9.

iGEM MEET-UPS

We attend to two iGEM meet-ups, an European one, and an other, gathering the Parisian teams. We were part of the organisation of the Parisian meet-up.

This meet-ups helps us in two ways. First it was a great opportunity to have a feed-back from our peers. Then, we met there other teams working with CRISPR-Cas9, and lead collaborations with them.

IV/ Responsiveness

What did we learn ?

Leading a project on fundamental biology involves to work a lot with stakeholders. In a RRI vision, a fundamental project is an opportunity to think about the responsability of science, in our case CRISPR-Cas9. We learned we should follow the principles of RRI to have the strongest connection between innovation and the societal needs.

The we saw that the potentiality of CRISPR-Cas9 was huge. This leads to two things:

- It’s very difficult to define precisely what could be the impacts, thus a harder work must be furnished on the subject;

- Vulgarisation for the public is a key issue.

CRISPR-Cas9 is easy to use, even by students and has big consequences. We should define the purposes with more rigor and strengthen the safety part.

Using CRISPR-Cas9 requires to know about the gene before we can mutate its functions. This requires to work on genes we already know about or to have a strong research on the gene.

In the ethical field we should always balance the advantages and the disadvantage. Even if it seems obvious, it is fundamental to do this and to present the balance to the public opinion.

RRI Test : the answers of the iGEM teams

We asked iGEM teams to fill to our test. 17 teams answered to it, and thus helped us to see how the principles of RRI are respected in the iGEM competition. Their answers gave us new ideas to spread this principles, but also make us thought on how to improve the knowledge of this principles.

Firstly, we saw that the RRI principles were not really known among iGEM teams : only 53% of the teams knew what it is.

I. Reflexivity

iGEM projects do meet societal goals. Most of them wants to address a major challenge of our time and solve it by synthetic biology. However, the definition of a societal need is very different from teams to teams.

The main question is : how to define a societal need ?

There is a lot of different projects, and a few ways to define the societal need the team wants to address : news report, questionnaire survey, meeting stakeholders, research in scientific papers. Other teams defined their project by their own knowledge but then meet stakeholders to build it.

Defining a societal need comes along with the question of the project itself : how did the team find the problem they want to address ?

Most of the teams looked around them: local problem of flu, Lascaux cave, problem of small and local research center, or major problems making the news, like Zika viruses or life on Mars, or just a desire to improve synthetic biology. A good example : iGEM Costa Rica decided to tackle prostate cancer because it is the second cause of mortality in their country.

In order to answer a societal need the teams need to identify to whom the project will apply, who will use it. Some teams like iGEM Istanbul Tech or iGEM Pasteur gives a really complete scenario of who will use it and how. Despite this teams, the users of the project are not always defined.

The definition of the potential impacts is also a problem, because most of the team didn’t try to define it. We could think of a solution : we know Synenergene asks each year some teams to define a techno-moral scenario about their project. Techno-moral scenario could be spread in order to think about concrete applications. Moreover, an other work could be to think about a scenario of the worst application possible on the innovation. It would be a difficult but interesting exercise.

II. Anticipation

The answers of the test show the anticipation part is not well developed among iGEM teams. Most of the team admits they are waiting for the results to build an anticipation. This lack of anticipation is quite normal because the iGEM competition does not call projects to go beyond the competition. However, we think iGEM could play an important part for the spread of a principle of anticipation among researchers.

Teams which tried to anticipate want to make a new firm, in order to sell their new product. Other teams wants beyond iGEM to pursue the project by extending it to new fields (iGEM Manchester), or help other scientists (iGEM Istanbul Tech).

About the legal framework. If the bulk of the teams chose patent over open license for their project, most of them preferred a patent with humanitarian licensing than a traditional patent. It shows how teams wants to respond to societal needs.

We believe iGEM could be a great laboratory for definition and test of legal frameworks. The legal framework is different for each project. This legal framework could be defined at the beginning of the project, in order to see what would be the best choice for the project to be economically interesting and meet societal goals. The anticipation of the framework could help the team to shape their projects and the goals they want them to reach.

III Inclusiveness

Inclusiveness is one of the principles the most shared among iGEM teams. iGEM teams meets as many stakeholders as there are project. If we give a quick glance at it we can find among stakeholders : governmental agencies, farmers narcotic police officers and academicians, city hall, doctors, vets, European agency… Among this very different stakeholders, there is a lot of industry actors, showing that teams think how their project should be developed.. Sometimes there is a difficulty to meet industry actors in very specific fields (like space).

Because of the work of the iGEM competition on this field, popular science and outreach are well admitted and used among teams. Most of the teams lead actions of popular science among public or students.

iGEM meet-ups are also important for inclusiveness. According to the answers they are often useful for the teams, they permit to increase the feasibility of the project. For example, a team discovered potential impacts while talking with iGEM teams at a meet-up.

In order to foster Inclusiveness the iGEM competition created in 2015 a special prize for Public Engagement. We believe it could be a good idea in the iGEM competition to have prize for Reflexivity and Anticipation (Responsiveness is already a price through the Integrated Human Practices.

IV Responsiveness

Teams had really interesting answers on how the different steps highlighted by the test helped them to reshape their project, even if some teams have not seen their project reshaped. They found it useful to decide where they should direct the development of their project, and how to build feasible and long lasting project, positive for society.

We could take the iGEM Valencia UPV as an example: after talking with farmers they understood their tool could not be used by farmers, and so aimed plant breeders.An other team realized they have to put more inclusiveness in their project.

iGEM Imperial members noticed how the principles changed the way they think about their project :

« Those processes shaped the way we now approach decision making during our project. They guide us through a logical, rational and societal process every time we pivot. »

And the last words to the iGEM CGU Taïwan members, who summed it up in the best way possible :

« Reflexivity makes you a good start; inclusiveness makes you a good connection; anticipation makes you a good hope. »

The question of evaluation ?

Doing the test is already providing a feed-back on the project. Should this feed-back be completed by an evaluation of the respect of the RRI principles ? Such a tool would be useful to know where the team can improve. However the ways to respect RRI principles are diverse, and we saw teams can invent new ways to respect it every day. All of the criteria needed for an evaluation would never fit in a single evaluation, because the answers are so diverse, and new ways to address RRI principles can be invented by each team.

We prefer to think the RRI Test as a helping tool for teams to think on their project, a feed-back in which they can have a look back on the choices that were made and their compliance with RRI principles.

References

I Reflexivity

How did the team thought about their project and defined it ?

iGEM projects do meet societal goals. Most of them wants to address a major challenge of our time and solve it by synthetic biology. However, the definition of a societal need is very different from teams to teams.

The main question is : how to define a societal need ?

There is a lot of different projects, and a few ways to define the societal need the team wants to address : news report, questionnaire survey, meeting stakeholders, research in scientific papers. Other teams defined their project by their own knowledge but then meet stakeholders to build it.

Defining a societal need comes along with the question of the project itself : how did the team find the problem they want to address ?

Most of the teams looked around them: local problem of flu, Lascaux cave, problem of small and local research center, or major problems making the news, like Zika viruses or life on Mars, or just a desire to improve synthetic biology. A good example : iGEM Costa Rica decided to tackle prostate cancer because it is the second cause of mortality in their country.

In order to answer a societal need the teams need to identify to whom the project will apply, who will use it. Some teams like iGEM Istanbul Tech or iGEM Pasteur gives a really complete scenario of who will use it and how. Despite this teams, the users of the project are not always defined.

The definition of the potential impacts is also a problem, because most of the team didn’t try to define it. We could think of a solution : we know Synenergene asks each year some teams to define a techno-moral scenario about their project. Techno-moral scenario could be spread in order to think about concrete applications. Moreover, an other work could be to think about a scenario of the worst application possible on the innovation. It would be a difficult but interesting exercise.

II. Anticipation

How the iGEM team anticipated the problems their project could meet, but also think about the future of the project, beyond iGEM ?

The answers of the test show the anticipation part is not well developed among iGEM teams. Most of the team admits they are waiting for the results to build an anticipation. This lack of anticipation is quite normal because the iGEM competition does not call projects to go beyond the competition. However, we think iGEM could play an important part for the spread of a principle of anticipation among researchers.

Teams which tried to anticipate want to make a new firm, in order to sell their new product. Other teams wants beyond iGEM to pursue the project by extending it to new fields (iGEM Manchester), or help other scientists (iGEM Istanbul Tech).

About the legal framework. If the bulk of the teams chose patent over open license for their project, most of them preferred a patent with humanitarian licensing than a traditional patent. It shows how teams wants to respond to societal needs.

We believe iGEM could be a great laboratory for definition and test of legal frameworks. The legal framework is different for each project. This legal framework could be defined at the beginning of the project, in order to see what would be the best choice for the project to be economically interesting and meet societal goals. The anticipation of the framework could help the team to shape their projects and the goals they want them to reach.

III Inclusiveness

Inclusiveness is one of the principles the most shared among iGEM teams. iGEM teams meets as many stakeholders as there are project. If we givea quick glance at it we can find among stakeholders : governmental agencies, farmers narcotic police officers and academicians, city hall, doctors, vets, European agency… Among this very different stakeholders, there is a lot of industry actors, showing that teams think how their project should be developed.. Sometimes there is a difficulty to meet industry actors in very specific fields (like space).

Because of the work of the iGEM competition on this field, popular science and outreach are well admitted and used among teams. Most of the teams lead actions of popular science among public or students.

iGEM meet-ups are also important for inclusiveness. According to the answers they are often useful for the teams, they permit to increase the feasibility of the project. For example, a team discovered potential impacts while talking with iGEM teams at a meet-up.

IV Responsiveness

Teams had really interesting answers on how the different steps highlighted by the test helped them to reshape their project, even if some teams have not seen their project reshaped. They found it useful to decide where they should direct the development of their project, and how to build feasible and long lasting project, positive for society.

We could take the iGEM Valencia UPV as an example: after talking with farmers they understood their tool could not be used by farmers, and so aimed plant breeders.An other team realized they have to put more inclusiveness in their project.

iGEM Imperial members noticed how the principles changed the way they think about their project :

« Those processes shaped the way we now approach decision making during our project. They guide us through a logical, rational and societal process every time we pivot. »

And the last words to the iGEM CGU Taïwan members, who summed it up in the best way possible :

iGEM CGU Taïwan

« Reflexivity makes you a good start; inclusiveness makes you a good connection; anticipation makes you a good hope. »

The question of evaluation ?

Lagomarsino MC, Espéli O, Junier I. From structure to function of bacterial chromosomes: Evolutionary perspectives and ideas for new experiments. FEBS Letters. 7 oct 2015;589(20PartA):2996‑3004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2015.07.002

König H,Dorado‐Morales P, Porcar M, Responsibility and intellectual property in synthetic biology, A proposal for using Responsible Research and Innovation as a basic framework for intellectual property decisions in synthetic biology, EMBO Reports, EMBO reports (2015) 16, 1055-1059. http://embor.embopress.org/content/16/9/1055