Martin sim (Talk | contribs) |

Martin sim (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 747: | Line 747: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| − | + | <p><figcaption>Table 6: Genetic parts required for the assembly of the 'Biological capacitor' construct</figcaption></p> | |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="mfc-porin-overexpression"> | ||

<h3>Porin Overexpression for Microbial Fuel Cells</h3> | <h3>Porin Overexpression for Microbial Fuel Cells</h3> | ||

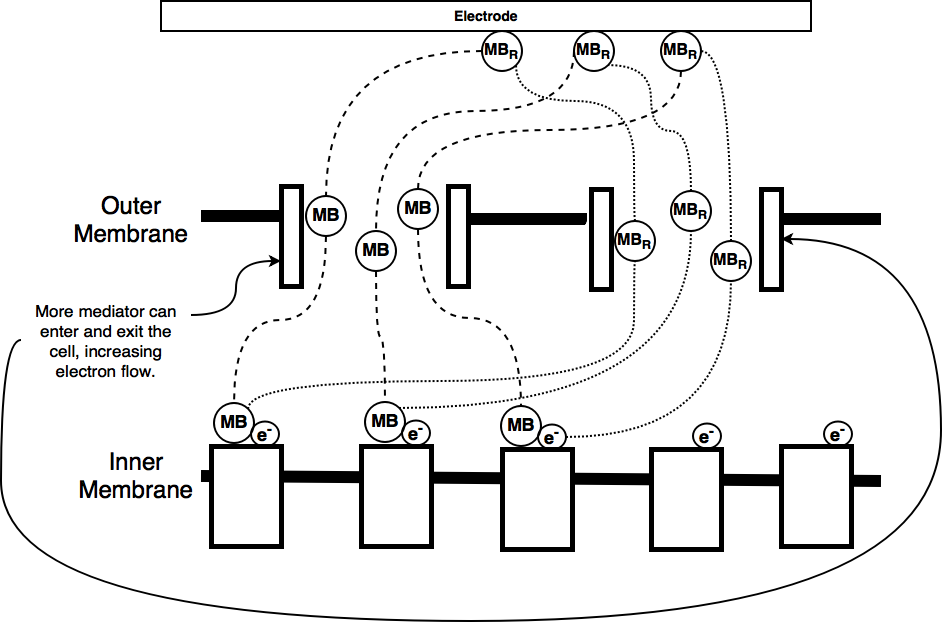

<p>As part of our iGEM project we worked on trying to improve the current output from a microbial fuel cell. Microbial fuel cells which use <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> depend on a mediator, usually methylene blue to transfer electrons between the electrodes of the fuel cell and the organism's electron transport chain. The mediator enters the cell through porins in the cell membrane and 'steals' electrons, therefore becoming oxidised. These electrons are then carried to the positively charged cathode, where they are lost, allowing electrons to flow around the circuit.</p> | <p>As part of our iGEM project we worked on trying to improve the current output from a microbial fuel cell. Microbial fuel cells which use <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> depend on a mediator, usually methylene blue to transfer electrons between the electrodes of the fuel cell and the organism's electron transport chain. The mediator enters the cell through porins in the cell membrane and 'steals' electrons, therefore becoming oxidised. These electrons are then carried to the positively charged cathode, where they are lost, allowing electrons to flow around the circuit.</p> | ||

| Line 806: | Line 816: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><figcaption>Table 7: Genetic parts required for the assembly of the OmpF 'Microbial Fuel Cell' construct</figcaption></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<p>We are also investigating an alternative way of increasing the amount of mediator transport through our work which is the expression of a larger membrane porin. One of the limiting factors of a microbial fuel cell is the low permeability of the cell membrane, which limits mediator transport. Team Bielefeld in 2013 expressed the OprF porin protein from <em>Pseudomonas fluorescens</em> in <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> which increased cell membrane permeability. This is because the porin size is much larger than <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> natural porins (such as OmpF, above). This allows more mediator to pass through the membrane.</p> | <p>We are also investigating an alternative way of increasing the amount of mediator transport through our work which is the expression of a larger membrane porin. One of the limiting factors of a microbial fuel cell is the low permeability of the cell membrane, which limits mediator transport. Team Bielefeld in 2013 expressed the OprF porin protein from <em>Pseudomonas fluorescens</em> in <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> which increased cell membrane permeability. This is because the porin size is much larger than <span class="species-name">E. coli</span> natural porins (such as OmpF, above). This allows more mediator to pass through the membrane.</p> | ||

<p> | <p> | ||

| Line 858: | Line 872: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><figcaption>Table 8: Genetic parts required for the assembly of the OprF containing 'Microbial Fuel Cell' construct</figcaption></figure></p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 14:21, 17 October 2016

Parts

You can also find all the parts we've designed in the parts registry. We've used SBOL visual to specify our designs.

PhtpG Electrically Induced 'Light Bulb'

We aimed to engineer Escherichia coli (E. coli) such that it fluoresces when an electrical current is passed through its growth medium, via the use of an inducible promoter responsive to one of the by-products of electricity passing through a liquid - heat.

HtpG is a stress protein in E. coli, produced during conditions of cellular stress including heat. Previous work has shown that htpG expression increases under high temperature conditions, for example, 45°C. The promoter PhtpG lies upstream of htpG and regulates the gene’s expression in response to heat.

The E. coli sigma factor 32 is required to bind to RNA polymerase holoenzyme in order to drive transcription of genes downstream of PhtpG. Sigma32 (σ32) is a product of the rpoH gene. Our design includes additional restriction sites up and downstream of rpoH (BamHI and BglII respectively) to allow us to either remove rpoH, or add further copies of this gene to the construct. The rationale behind this is to tune the sensitivity of the PhtpG heat shock response via the cellular abundance of σ32 and RNA polymerase activity. For example, having extra copies of rpoH expressed as a result of a small variation in heat would act as a positive feedback loop to amplify PhtpG activity and accordingly, the overall expression of the downstream genes in our operon construct.

To monitor the response of cells to the heat shock response, and to produce a ‘lightbulb’, we will use Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). GFP is a jellyfish derived protein often used as a reporter of promoter activity. We are using a variation of GFP, the superfolder GFP (sfGFP) as this generates a greater fluorescent signal when excited with light at 485nm. In terms of this experiment, sfGFP will be used to ensure the construct works and that our cells are indeed responsive to an electric current via heat shock stimulation of PhtpG. Higher heat-shock temperatures would hopefully result in greater sfgfp expression due to higher PhtpG activity, measured through plate reader assays. As with the rpoH gene, we have incorporated two restriction sites (BsmBI for Golden Gate cloning) up and downstream of the gene. This will allow us to change sfGFP for other reporters, such as luciferase. Luciferase would allow the emission of light like an actual lightbulb unlike sfGFP which requires an excitation wavelength of light to generate fluorescence.

Our design utilizes the natural ribosome binding site (RBS) present upstream of rpoH in E. coli, which we will be adding to the registry (BBa_K1895001). This is to ensure that the ribosome does bind to the mRNA and translate the protein correctly without potential adverse effects that a non-native RBS may have. We will however make variants of the RBS with two different medium bicistronic RBS in order to modulate the transcription of the transcribed mRNA encoding σ32. The medium strength bicistronic RBS will avoid the problem of placing too high a translational burden on the cell. We will then test all three variants to determine the best RBS to use in the final design.

Upstream of sfGFP, we will use the BBa_0034 high strength RBS for maximum translation of sfGFP.

Our Construct

Caution: When getting our lightbulb construct synthesised, we encountered issues with the synthesis of the terminator (part BBa_B1006) used in this design. As this was delaying our progress, we decided to request the construct without a terminator, and then to clone this in ourselves at a later point. Unfortunately due to running out of time we were unable to do this and so our final construct as used and characterised does not include a terminator downstream of sfGFP. We have detailed this on the parts page of the registry. If you use our construct, consider adding BBa_B1006 as we planned or using an alternative such as BBa_B0012 which we use in later designs.

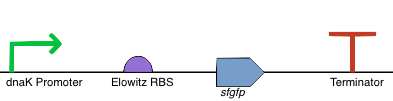

Alternative 'Light Bulb' construct using PdnaK inducible promoter

One of the concerns we had with our lightbulb construct is that, due to the inclusion of the rpoH coding sequence we would end up causing the expression of sfgfp without inducing the circuit through heat. We thought that this could occur because it is impossible for any promoter to be fully 'off', that is, there is always some constituitive expression. As a result of this constituitive expression σ32 would be produced which would in turn induce the htpG promoter causing run-away amplification of the circuit and high levels of sfgfp expression.

To preempt these difficulties we also designed a construct without amplification using an alternative heat-shock promoter, the dnaK promoter. The role of dnaK is that of a protein chaperone, it binds to proteins that have misfolded due to the stress. These proteins are then refolded in an HSP-mediated process or degraded (Arsène F, et al., 2000). Like other members of the Hsp70 family, dnaK in E. coli is upregulated by heat stress (Ritossa, F., 1996). Consequently its promoter must be stronger during heat shock to allow for overexpression. As heat stress can be triggered by the joule effect heating, that is heat produced by passing an electric current through a medium, systems with dnaK as their promoter we hypothesize be able to be induced electrically. We designed this construct to test that hypothesis.

Our Construct

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_R0080 | dnaK Promoter | This is the dnaK promoter, it is upregulated in E. coli by heat shock causing increased downstream expression. |

| BBa_R0034 | Elowitz RBS | This is a standard RBS based that used in the construction of the repressilator (Elowitz, 1999). We chose it as it has a high efficiency RBS and is widely used in iGEM projects. |

| BBa_I746916 | Superfolder GFP | This is the coding sequence for super folder GFP. We have chosen to use this as our reporter because it can easily be quantified using a plate by taking the OD600 measurement. This is harder to quantify with more visible reporters like amilCP. |

| BBa_B0012 | Terminator | This is a standard, widely used terminator in iGEM projects. We switched to using this terminator when we had synthesis problems with the double loop terminator used in our other constructs (BBa_B1006). |

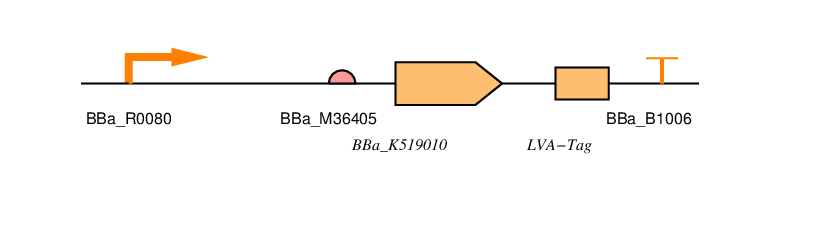

Arabinose Controlled 'Variable Resistor'

One of the key components in an electrical circuit is the resistor, used to reduce current flow and adjust output signal levels. We plan to produce a device within Escherichia coli to generate a response analagous to a variable resistor. Our device will aim to vary the amount of free ions in an electrolyte. Ion uptake will be controlled by the expression of smtA. SmtA is a metallothionein that can bind to heavy metal ions like Cadmium (II), Zinc (II) and Copper (II).

SmtA has been used in a number of iGEM projects and is in the registry (BBa_K519010). It has previously been used in experiments for Cadmium (II) uptake, see Tokyo-NokoGen 2011. We will be examining firstly, the impact of SmtA of Zinc (II) concentration rather than Cadmium (II) and then the impact that this has on the resistivity of the Zinc (II) containing media. In this instance we will be using Zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) in solution where it disassociates into Zn2+ and SO42- ions. Various concentrations of Zinc sulfate have known electrical conductivity. When smtA is expressed it will render the Zn2+ unavailable and thereby reduce the conductivity of the solution.

We will be placing smtA under the control of an AraC regulated promoter (PBad) allowing the expression of smtA to be controlled by the addition or removal of arabinose.

Our Construct

We will be synthesising two variants of our construct, one with and one without an ssRA degradation tag. The presence of a degradation tag causes the protein to be degraded by one of two proteases ClpXP or ClpAP. Their normal function is to prevent the ribosome from becoming ‘stuck’ on truncated mRNA. The addition of a degradation tag will allow us to see if we gain finer control over the resistance by increasing the rate of protein degradation. Both variants of the construct will include a polyhistidine-tag to allow for protein purification from cultures.

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_R0080 | AraC regulated promoter | This is the AraC regulated promoter. Transcription from this promoter takes place in the presence arabinose. Without arabinose present there should be no transcription as AraC will block transcription occurring. | BBa_B0034 | Standard RBS | This is a standard RBS based that used in the construction of the repressilator (Elowitz, 1999). This is a high efficiency RBS and is widely used in iGEM projects. It is also present in the 2016 distribution kit. | BBa_K519010 | SmtA Coding Sequence | This is the coding sequence for SmtA originally from Synechococcus spp , a cyanobacterial strain. | LVA-TAG | Degradation Tag | This is an ssRA protein degradation tag. Tagged proteins are degraded by the proteases ClpXP or ClpAP. There are a number of tag sequences, variants of AANDENYALAA, with the last three amino acids varying. The last three amino acids determine the half-life of the protein. LVA is a fast protein degradation tag. We use this to ensure that the resistance is reduced quickly after removal of arabinose. | BBa_B1006 | Terminator | This is an artificial terminator part and was chosen because it has a high forward efficiency of 0.99. | pSB1C3 | Backbone | We are using the standard BioBrick backbone part pSB1C3 as this will make it easier to submit the part to the registry at a later date. We have also included restriction sites around protein and tag so that it can be replaced with a part without the tag to see if this has any effect on Zinc uptake. |

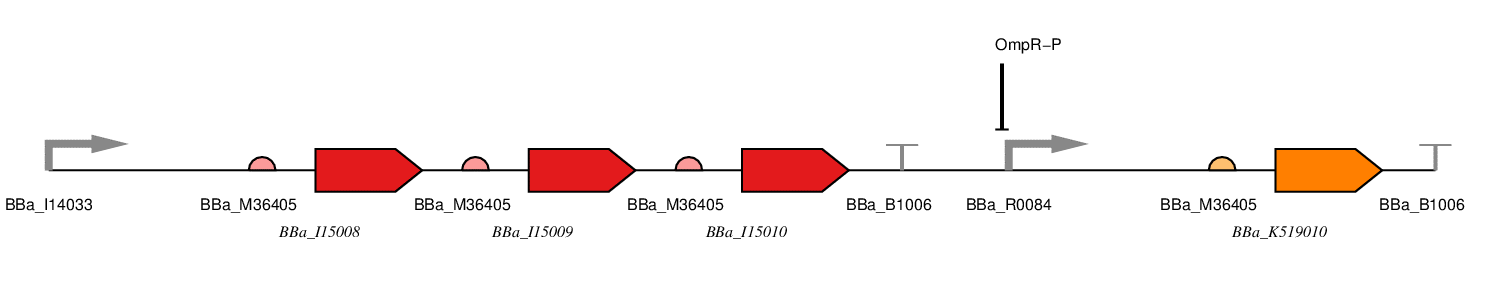

OmpR Controlled Red 'Light Dependent Resistor'

We plan to engineer E. coli to behave like a light dependent resistor (LDR). A light dependent resistor (or photoresistor) varies its resistance with light intensity. Ordinarily, the resistance of an LDR decreases with increasing incident light and vice versa. We aim to do this by using E. coli to vary the amount of free ions in an electrolyte in response to light. Ion uptake will be controlled by the expression of smtA. As described above, SmtA is a metallothionein that can bind to heavy metal ions like Cadmium (II), Zinc (II) and Copper (II).

SmtA has been used in a number of iGEM projects and is in the registry (BBa_K519010). It has previously been used in experiments for Cadmium (II) uptake, see Tokyo-NokoGen 2011 and for accumulating Zinc (II) intracellularly. We will be examining firstly, the impact of SmtA on Zinc (II) concentration rather than Cadmium (II) and then the impact that this has on the resistivity of the Zinc (II) containing media. In this instance we will be using Zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) in solution where it disassociates into Zn2+ and SO42- ions. Various concentrations of Zinc sulfate have known Electrical conductivity . When smtA is expressed it will render the Zn2+ unavailable and thereby reduce the conductivity of the solution.

For this LDR we will be using the red light detection system from the Colliroid project ( paper). In this scheme the production of SmtA which affects the resistivity is placed under the control of the OmpF upstream promoter (BBa_R0084). We propose to engineer a system where this promoter is repressed in the dark and has increased transcription in (red) light. This allows the device to mimic the behaviour of a traditional electronic LDR whereby resistance is decreased in the light and increased in the dark.

The OmpF promoter is repressed by phosphorylated OmpR, OmpR-P. In normal conditions the E. coli cell contains free OmpR which can be phosphorylated by expression of a protein with an EnvZ domain. One such protein is the fusion protein, Cph8 (BBa_I15010). In the dark this protein phosphorylates OmpR and so prevents SmtA production, increasing the ‘resistance’ on the OmpF promoter. In the light, the light responsive domain Cph1 inhibits the activity of the EnvZ is prevented from phosphorylating OmpR and therefore allows SmtA production and decreased resistance.

Note that this will only work in E. coli which are naturally deficient in EnvZ.

In order for the light responsive domain of the fusion protein Cph8 to sense red light, the formation of a chromophore is required. This is done by the production of two proteins, HO1 and PcyA together with the Cph8. In our system these will be constitutively expressed to create the red light sensor.

Our Construct

There are two parts to our construct, the red light sensing component and the SmtA production component. It is presented below as a one plasmid system with the following parts.

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_J23100 | E. coli constitutive promoter | We will use a constitutive promoter regulated by the E. coli housekeeping σ70 sigma factor. Consequently, there should be active RNA polymerase present to transcribe from this promoter at all stages during the bacterial growth cycle, but in particular during exponential growth. We have chosen BBa_J23100, an artificial promoter due to its widespread use, documentation and comparatively short sequence (35bp). |

| BBa_I15008 | HO1 | This is one of the proteins required for chromophore formation. |

| BBa_I15009 | PcyA | This is another of the proteins required for chromophore formation. |

| BBa_I15010 | Cph8 | This is a fusion protein consisting of a light receptor domain and EnvZ domain. In the dark the EnvZ domain of this protein phosphorylates free OmpR in the cell which represses the OmpF promoter and induces the OmpC promoter. |

| BBa_R0084 | OmpR-P Promoter | This part is the promoter usually found upstream of OmpF. It is repressed by phosphorylated OmpR. |

| BBa_K519010 | SmtA | This is the coding sequence for SmtA originally from Synechococcus spp, a cyanobacterial strain. |

| BBa_B1006 | Terminator | This is an artificial terminator part and was chosen because it has a high forward efficiency of 0.99. |

| pSB1C3 | Backbone | We are using the standard BioBrick backbone part pSB1C3 as this will make it easier to submit the part to the registry at a later date. |

LDR construction

All parts listed above aside from Cph8 are provided in the 2016 iGEM distribution. Cph8 (BBa_I15010) is however available to order from the registry. The remaining parts are in the distribution so BioBrick assembly can be performed. However because of the large number of parts, and there are no intermediaries in the registry or distribution kit, this construct would be unwieldy to assemble in this manner.

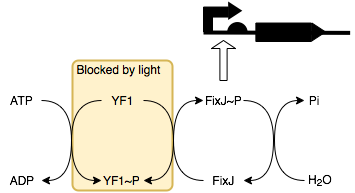

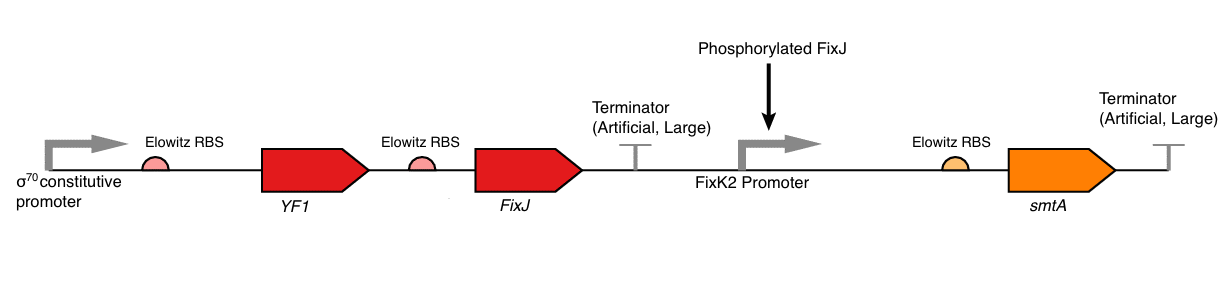

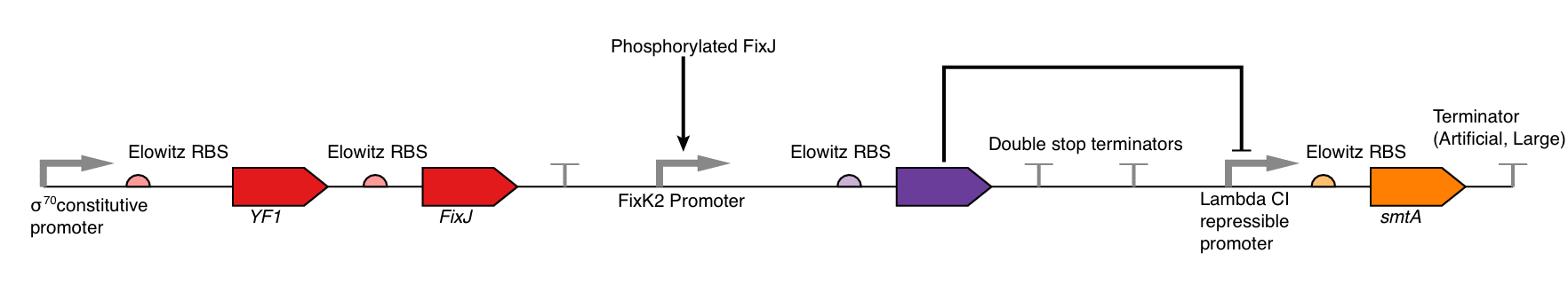

YF1-FixJ Controlled Blue 'Light Dependent Resistor'

We can also produce a variation of our LDR to have a construct regulated by blue light. By placing smtA under the control of a FixJ-P (phosphorylated FixJ) promoter, this allows it to be regulated by blue light through a series of reactions with its response regulator protein YF1 (below).

In the absence of light, YF1 undergoes autophosphorylation to produce YF1-P which can then phosphorylate FixJ. This in turn activates the transcription of the downstream protein, which in this case, is SmtA. Thus, in the presence of light, SmtA is not produced and so conductivity does not change, whilst in the absence of light SmtA is produced resulting in a decrease in resistance.

Clearly, this behaviour is the inverse of an electrical LDR where resistance increases with light intensity. To mimic this behaviour using biological circuits we would place an inverter before the FixK2 promoter (which is activated by FixJ-P). The inverter is constructed by placing the desired output, here SmtA, under the control of a lambda cl regulated promoter (BBa_R0051). As lambda cl represses the promoter having this produced under control of FixK2 promoter inverts the system so that SmtA is produced in the presence of light rather than the absence thereof. BBa_K592020 is an example of a part that uses this technique.

Our Construct

The non-inverted construct is shown in Figure 6a and 6b and the inverted construct in Figure 6c and 6d. Currently our device is shown as a single plasmid system but there is no reason that the two separate sub-components could not be split into a dual plasmid system (with compatible origins of replication and differing resistance markers) for easier assembly.

For the non-inverted construct the parts are as follows:

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_J23100 | constitutive promoter | We will use a σ70 constitutive promoter as this is the main E. coli sigma factor. Consequently, there should be RNA polymerase present to transcribe from this promoter at all stages during the bacterial growth cycle. Specifically, we have chosen BBa_J23100, an artificial promoter due to its widespread use, documentation and comparatively short sequence (35bp). |

| BBa_K592016 | FixJ & YF1 with RBSs | The YF1 and FixJ coding sequences are provided as a composite part together with standard RBSs in part BBa_K592016 which we have chosen for ease of assembly, in the event that we or future teams wish to use the BioBrick standard assembly to produce our part. |

| BBa_K592006 | FixK2 promoter | This is the wild-type promoter to which phosphorylated FixJ binds. It is reported that this promoter has very little leaky activity in the absence of FixJ. |

| BBa_K519010 | SmtA | This is the coding sequence for SmtA originally from Synechococcus spp, a cyanobacterial strain. |

| BBa_B1006 | Terminator | This is an artificial terminator part and was chosen because it has a high forward efficiency of 0.99. |

| pSB1C3 | Backbone | We are using the standard BioBrick backbone part pSB1C3 as this will make it easier to submit the part to the registry at a later date. |

For the inverted part there are additional parts as follows:

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_C0051 | Lambda CI | This is the repressor protein from Lambda phage it represses the promoter BBa_R0051. |

| BBa_B0010, BBa_B0012 | Double stop terminators | These are the terminators used in the composite part BBa_S04617 which is replicated in our construct. |

| BBa_R0051 | Lambda CI controlled promoter | This is a promoter from Lambda phage that is repressed by lambda Cl (BBa_C0051). |

Construction and BioBrick assembly

We can construct this device using synthesised gBlocks from our free allowance provided by IDT.

There exist a number of intermediate assembly components in the parts distribution that can be used to assemble our part faster if we use BioBrick assembly. Notably, BBa_S04617 contains the inverter, BBa_K592016 contains the FixJ and YF1. The two devices can be constructed separately as follows:

Constitutive Production Device

-

Digest the terminator BBa_B1006 with EcoRI & XbaI and purify.

-

Digest BBa_K592016 with EcoRI & SpeI and purify.

-

Mix both parts & Ligate to form intermediate YF1FixJ+Terminator construct.

-

Digest the intermediate YF1FixJ+Terminator construct with EcoRI & XbaI and the constitutive promoter BBa_J23100 with EcoRI & SpeI.

-

Mix and ligate these to form the constitutive production device.

SmtA Expression Device (inverted):

-

Digest BBa_K519010 with EcoRI & XbaI and purify.

-

Digest BBa_S04617 with EcoRI & SpeI and purify.

-

Mix and ligate to produce intermediate part: inverted SmtA production.

-

Digest terminator with EcoRI & XbaI.

-

Digest inverted SmtA production intermediate with EcoRI & SpeI.

-

Mix and ligate purified parts together to produce SmtA expression device.

To produce the non-inverted device replace BBa_S04617 with the SmtA coding sequence and use an additional step to join this to an RBS, we suggest the standard RBS BBa_B0034 as this has good efficiency.

Biological 'Capacitor'

We plan to engineer E. coli to mimic one of the properties of a capacitor; the ability to accumulate and hold charge for some time before discharging. This is shown in the idealised graph below.

An electrical capacitor accumulates charge whilst a voltage is applied and then discharges when the voltage stops being applied. We make an analogy between the outputs of voltage signal and protein concentration. Whereas an electrical capacitor accumulates charge, a biological ‘capacitor’ would accumulate proteins. As an electrical capacitor has a maximum charge it can accumulate, within a bacterial cell there is a maximum protein concentration that can accumulate as determined by its production and degradation rate. Once proteins stop being accumulated in the cell it ‘discharges’ by having these drive the production of an output signal.

In this construct we use L-arabinose to mimic a voltage signal. This is entirely for experimental purposes, there is no reason that this device cannot be modified to respond to a stress signal, for instance through the PhtpG heat shock response promoter explored elsewhere in our work. Although in this case we show that proteins can be accumulated there is no reason why actual charge, in the form of a potential difference could not be generated across the cell membrane. There are already examples of membrane potentials in biology, the most obvious being found in neurons. This is something that has been explored by iGEM teams in the past e.g., Cambridge (2008). Importantly we show through modelling that the charge-discharge cycle can be mimicked in biological cells through the use of repressor/inducer competition. This could be merged with work on membrane potentials in the future.

Because we use a constitutively on promoter, the TetR repressible promoter (BBa_R0040) the default state of the system is ‘charging’. In this state lambda repressor (BBa_C1051) accumulates in the cell together with 434 repressor (BBa_C0052). The amount of 434 repressor grows faster than that of lambda repressor because there are two coding sequences for the protein in the circuit. This is to ensure that it outcompetes (on average) the lambda repressor so that there is a low output signal whilst in the charging state. This occurs because 434 repressor represses the output promoter whilst lambda repressor induces it. In out device the output signal is sfGFP (BBa_I746916).

We can switch the state of the system to the discharging state by causing the expression of TetR. To facilitate this we have used an L-arabinose promoter coupled with the TetR coding sequence to give us a chemical ‘off switch’. Once TetR is produced the system enters the discharging state, as no further protein synthesis in our construct is induced, and so the amount of 434 repressor and lambda repressor start to decay. The 434 repressor is tagged with a very fast ssRA degradation tag, the LVA degradation tag so that it will be broken down faster than lambda repressor.

As this happens, there will reach a point where the 434 repressor stops out-competing the lambda repressor and the output will start to be produced as it is induced by the lambda repressor. The level of 434 and lambda repressor will continue to fall until the output stops being produced and the system has completely ‘discharged’ and is in a resting state. At this point the removal of L-arabinose and the addition of tetracycline or an analogue thereof (which binds to TetR and prevents it from repressing the promoter) would switch the system back into the charging state and the process can begin again.

Construct

Our construct, as shown here, is a composite device which is built entirely of BioBrick parts already in the registry.

The parts used are as follows:

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_R0080 | L-Arabinose inducible promoter | This part is an L-Arabinose inducible promoter with very low level expression in the absence of L-Arabinose. Be aware, if the E. coli strain used constitutively expresses AraC then this promoter will ‘leak’. Check the strain list for information. |

| BBa_R0040 | TetR | This is the coding sequence for TetR which represses BBa_R0040. |

| BBa_R0040 | TetR Repressible Promoter | This promoter can be repressed by TetR. Be aware, if the strain used expresses TetR constitutively then this promoter will be repressed. Check the strain list for information. |

| BBa_C0052 | 434 Repressor | Represses the output promoter. |

| BBa_C0051 | Lambda Repressor | Induces the output promoter. |

| BBa_I12006 | Modified Promoter Part | This is a modified promoter part, originally the lambda Prm promoter. The modification allows it to be activated by lambda repressor and repressed by 434 repressor. |

| BBa_I746916 | sfGFP | This is the coding sequence for super folder GFP. We have chosen to use this as our reporter because it can easily be quantified using a plate reader or microscopy. |

| BBa_B1006 | Standard Terminator | We chose to use this promoter from the registry as it has a high forward efficiency. |

| BBa_B0034 | RBS | We chose to use this RBS from the registry as it is efficient and widely used in iGEM projects. |

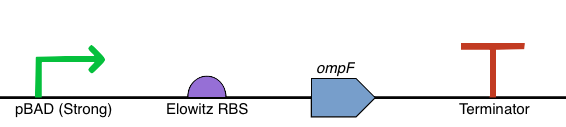

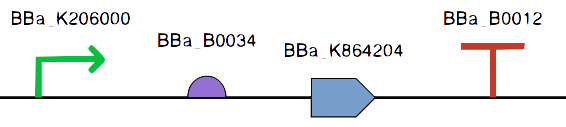

Porin Overexpression for Microbial Fuel Cells

As part of our iGEM project we worked on trying to improve the current output from a microbial fuel cell. Microbial fuel cells which use E. coli depend on a mediator, usually methylene blue to transfer electrons between the electrodes of the fuel cell and the organism's electron transport chain. The mediator enters the cell through porins in the cell membrane and 'steals' electrons, therefore becoming oxidised. These electrons are then carried to the positively charged cathode, where they are lost, allowing electrons to flow around the circuit.

By increasing the amount of mediator that can enter the cell we hope to be able to increase the electron flow rate, or current, from our microbial fuel cell. This occurs because the electrons can be moved more freely and their movement via the mediator is less limited by the rate at which the cell can transport the mediator across its membrane.

One of the ways of increasing the amount of mediator entering and exiting the cell is to increase the number of porins. For this purpose we have designed a device to control the overexpression of one of the porin OmpF.

We chose OmpF because it occurs naturally in E. coli and is suitable for the mediator we use in our fuel cell (which is a variant of the University of Reading's NCBE kit). OmpF is permeable for molecules smaller than 600 Da. Since methylene blue is 284 Da, it will pass easily through the OmpF pore.

By adding L-arabinose to the growth medium, the number of OmpF porins in the E. coli membrane should increase, allowing increased extracellular transport of methylene blue and faster electron shuttling between the cells and the electrodes. This should correspond to an increase in current. This function is shown below.

Our OmpF overexpression device is simple in construction, consisting of a PBad promoter, standard Elowitz RBS, the OmpF coding sequence and a standard terminator. We have added this as part number BBa_K1895004 in the registry.

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_K206000 | PBad Strong | Promotes the downstream expression of OmpF when L-arabinose is present in the growth medium. |

| BBa_B0034 | RBS (Elowitz) | A standard, efficient RBS, as used in our other constructs. |

| BBa_K864204 | OmpF | This is the coding sequence for OmpF, a natural porin protein found in E. coli. and involved in the transport of small molecules across the cell membrane. |

| BBa_B0012 | Terminator | This is a standard, widely used terminator in iGEM projects. We switched to using this terminator when we had synthesis problems with the double loop terminator used in our other constructs (BBa_B1006). |

We are also investigating an alternative way of increasing the amount of mediator transport through our work which is the expression of a larger membrane porin. One of the limiting factors of a microbial fuel cell is the low permeability of the cell membrane, which limits mediator transport. Team Bielefeld in 2013 expressed the OprF porin protein from Pseudomonas fluorescens in E. coli which increased cell membrane permeability. This is because the porin size is much larger than E. coli natural porins (such as OmpF, above). This allows more mediator to pass through the membrane.

One of the problems the Bielefeld team reported was the reduced growth of the E. coli due to metabolic stress. This is particularly noticeable when using the T7 promoter, as in their part BBa_K1172502. Population size is important for fuel cell output. The more cells there are, the more electron donors there are and so theoretically the greater the current. To overcome this issue we have changed their promoter to a PBad promoter which is regulated by L-arabinose monosaccharide. Thus replication stress is reduced during the first part of the growth curve. This should allow the bacterial population to grow rapidly in the fuel cell, ensuring we get a large population before L-arabinose is added (this increased level of growth should be seen by a higher OD600 value closer to 4.0 (growth of wild type) after 10 hours of growth). At this point the current should then further increase due to the larger porin expression.

This part is similar in construction to our OmpF expression part, with the protein coding sequence swapped to OprF rather than OmpR. This is part number BBa_K1895005 in the registry.

| Part No. | Name | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| BBa_K206000 | PBad Strong | Promotes the downstream expression of OmpF when L-arabinose is present in the growth medium. |

| BBa_B0034 | RBS (Elowitz) | A standard, efficient RBS, as used in our other constructs. |

| BBa_K1172501 | OprF | This is the coding sequence for OprF, a large porin protein found in Pseudomonas fluorescens. |

| BBa_B0012 | Terminator | This is a standard, widely used terminator in iGEM projects. We switched to using this terminator when we had synthesis problems with the double loop terminator used in our other constructs (BBa_B1006). |