| (97 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

<h1 style="color:#66b3ff">Insert title of page here!</h1> | <h1 style="color:#66b3ff">Insert title of page here!</h1> | ||

</div>--> | </div>--> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<!---------------------------Main content section of page-------------------------------> | <!---------------------------Main content section of page-------------------------------> | ||

<div class="content"> | <div class="content"> | ||

| − | + | <span class="ptitle">Overview</span> | |

| + | <p><span class="p">We modeled our system in silico to select a sterically feasible protecting group and to optimize a mutant leucyl-tRNA synthetase for complementarity of its catalytic site to protected leucine, and of its editing site to leucine. To select a protecting group, the team used protein-ligand docking software to compare binding affinities of several protected leucine/synthetase complexes. To perform mutagenesis on leucyl-tRNA synthetase, an integrated software script was written in the Linux shell, with inputs including a protein to mutate, a ligand, a list of residues of interest, and binding pocket location. The script runs mutagenesis, assesses mutant protein stability, then performs ligand docking. The outputs are ranked, simulating a streamlined mutagenesis optimization algorithm. We confirmed, using CSM software suites and iGEMDOCK, that leucine-AMP and leucine-AMS yield energetically comparable binding affinities to our synthetase. Lastly, we performed Michaelis-Menten modeling for the enzyme pepsin to gauge activity in nonspecific cleavage enzymes. | ||

| + | </span></p><br> | ||

| − | + | <span class="ptitle">Leucine Synthetase Selection</span><br><br> | |

| − | + | <span class="stitle">Synthetase File: 4aq7</span><br> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <p><span class="p">As stated in its documentation, 4aq7 | + | <p><span class="p">The leucine tRNA Synthetase (LeuS) used in the following simulations was found using the <a href="http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore.do?structureId=4AQ7" style="color:#235c81">RCSB Protein Data Bank</a>. The protein, named 4aq7, is a leucyl tRNA synthetase in its aminoacylation conformation. The following is a PyMol visualization of the protein that we compiled. |

| − | + | </span></p> | |

| + | |||

| + | <center><video controls="false" autoplay="autoplay" loop width="800" height="600" name="4aq7" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/0/07/T--Virginia--4aq7.mov"></video></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!--<div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:400px"> | ||

| + | <span><img style="height:100%;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/0/0f/T--Virginia--LeuS.jpg"/> | ||

| + | <br><i></i></span> | ||

| + | </div>--><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <span class="stitle">AMS vs AMP</span><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="p">As stated in its documentation, during the characterization of 4aq7, a leucyl-adenylate analogue was used to determine the crystal structure of the protein. By analyzing the file contents in PDBest, a PDB editor software, we identified the analogue as leucyl-AMS.</span></p><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">We constructed six different molecules with ChemSketch in order to determine whether the analogue significantly altered the conformation of LeuS. The constructed molecules were AMS and AMP adenylations of Cbz-leu, N-methoxycarbonyl-leu, and leucine. Using a variety of protein-ligand docking software like CSM-lig, Autodock Vina and iGEMDOCK, we were able to confirm that AMS (the adenylating agent found in the literature) and AMP yield similar binding affinities to the synthetase when bound with leucine. Thus, 4aq7 represents an protein that can accurately model our system containing leucyl-AMP and LeuS.</span></p><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:300px;position:absolute"> | ||

| + | <img style="height:110%;left:100px;position:absolute;left:-20px;" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/5c/T--Virginia--Cbz_Leu_AMS_AMP.jpg"/> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <div style="margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <p><span class="f">The above figure shows select data from CSM-lig comparing Cbz-leu-AMS (Left) and Cbz-leu-AMP (Right). The predicted affinity values (3.6 and 3.4, respectively) support the hypothesis that AMS and AMP result in structurally similar conformational changes of this leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Another 4 data runs were performed and can be found in the supplementary data section, but exhibit similar results.</span></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <span class="ptitle">Protecting Group</span><br><br> | ||

| + | <span class="stitle">Selection - Modeling Considerations</span><br> | ||

| − | + | <p><span class="p">Several programs were used to asses the viability of the different protecting groups in our system. The main programs used for this purpose were Autodock Vina, iGEMDOCK, and CSM-Lig. The initial tests measured residue specific energistic changes between different protecting groups. However, the binding affinities for all the protecting group choices were very similar, so we chose based on a different set of criteria. These are detailed in the following figure.</span></p><br><br> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:200px"> | ||

| + | <img style="height:100%" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/3b/T--Virginia--Pugh.jpg"/> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <p><span class="f">Pugh chart used to score and rank possible protecting groups. Some of the criteria are practical like the cost of the protecting group and enzyme. N-carbobenzyloxy (Cbz) produced the highest relative value on our chart and was chosen as a protecting group. </span></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| − | + | <span class="ptitle">Residue Selection</span><br><br> | |

| − | + | <span class="stitle">Literature</span><br><br> | |

| + | <p><span class="p">Half of our selected residues were intended to increase synthetase stability and reaction rates. These mutations were found by searching through current literature. We found four mutations that would improve LeuS, both through stabilization and altered editing capability. Of the four mutations, one is in the editing site while the other three are in miscellaneous locations around the protein. The editing site mutation, Thr 252, allows for the hydrolysis of Leu-tRNA, a crucial step in our overall project.<span class="references"><sup>22</sup><span class="refbox"><b>Reference:</b><br>Mursinna, R.S., Lee, K.W., Briggs, J.M., and Martinis, S.A. (2004). Molecular dissection of a critical specificity determinant within the amino acid editing domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 43, 155–165. | ||

| + | </span></span> The other stabilizing residues impact aminoacylation in two ways: through amino acid discrimination and tRNA binding<span class="references"><sup>21</sup><span class="refbox"><b>Reference:</b><br>Lue, S.W., and Kelley, S.O. (2007). A single residue in leucyl-tRNA synthetase affecting amino acid specificity and tRNA aminoacylation. Biochemistry 46, 4466–4472. | ||

| + | </span></span></span></p><br> | ||

| + | <span class="stitle">iGEMDOCK and Ligplot</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">To find residues of interest in the catalytic pocket, we used a combination of docking data as simulated in iGEMDOCK and of structural data visualized in Ligplot to determine additional mutational focci. iGEMDOCK is able to provide energy values for each residue by conducting an exhaustive docking search. Ligplot is capable of creating a 2D image of the binding site as detailed in the crystolography file. We selected mutations that satisfied two criteria. First, the residue had to have been shown to have a high energy during docking. Residues that returned large values in the protected leucine simulations were believed to have a high impact on the reduced viability of docking. The second criteria was location. Residues that protruded around the N terminus of leucine, the location the protecting group binds to, were thought to be possible sources of steric hindrance. A total of four residues that satisfied both criteria were selected: M40, Y41, L43 and D80.</span></p><br> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:400px"> | |

| + | <img style="height:100%"src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/c/cb/T--Virginia--LigPlot.jpg"/> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <p><span class="f">LigPlot generates both 2D and 3D images as shown above. Energistic relationships between molecules of 4aq7 are shown in detail in the 2D representation, and conformational analysis can be conducted on the 3D image.</span></p> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Final Selections</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Final Selections</span><br> | ||

<p><span class="p">The following residues were picked for mutagenesis.</span></p> | <p><span class="p">The following residues were picked for mutagenesis.</span></p> | ||

| − | <hX>Catalytic Site</hX> | + | <hX class="p"; font-size="20px"><b>Catalytic Site</b></hX> |

| − | <ul> | + | <ul class="p"> |

<li>M40</li> | <li>M40</li> | ||

<li>Y41</li> | <li>Y41</li> | ||

| Line 83: | Line 119: | ||

<li>D80</li> | <li>D80</li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| − | <hX>Editing</hX> | + | <hX class="p"; font-size="20px"><b>Editing</b></hX> |

| − | <ul> | + | <ul class="p"> |

<li>T252</li> | <li>T252</li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| − | <hX> | + | <hX class="p"; font-size="20px"><b>Stabilizing</b></hX> |

| − | <ul> | + | <ul class="p"> |

<li>K186</li> | <li>K186</li> | ||

<li>A293</li> | <li>A293</li> | ||

<li>L570</li> | <li>L570</li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

<span class="ptitle">MUT</span><br><br> | <span class="ptitle">MUT</span><br><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Purpose</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Purpose</span><br> | ||

| − | <p><span class="p"> In order to generate and test a large list of mutants we build a software pipeline in | + | <p><span class="p"> In order to generate and test a large list of mutants we build a software pipeline in Linux called MUT. MUT utilizes PyRosetta, Autodock Vina, and FoldX to mutate, test, and rank protein structures based on docking scores. This program was used to query for the optimal mutant structure for Cbz-Leu docking. The following is a visualization of our mutant synthetase with optimal structure.</span></p><br> |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <center><video controls="false" autoplay="autoplay" loop width="800" height="600" name="synthetase" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/34/T--Virginia--synthetase.mov"></video></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<span class="stitle">Structure</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Structure</span><br> | ||

| − | <p><span class="p">Upon initiation, MUT asks for four main inputs | + | <p><span class="p">Upon initiation, MUT asks for four main inputs: the protein pdb file that will be analysed, the residues that the program will mutate, the coordinates of the binding pocket for docking simulations, and a ligand pdb file. MUT first performs stability testing and docking to get baseline values for the future tests before it mutates the initial PDB file. At each iteration the residue is mutated to 17 other amino acids, not including Cys, Pro (as they induce kinks and are difficult to model) or itself. After mutagenesis is complete files undergo stability testing and docking to determine if the new mutant is stable and a better match for the ligand. Files that fail the tests go to the kennels. Below is a flowchart that explains the algorithm of the program.</span></p><br> |

| − | <p><span class="p">The kennel system allows for two levels of simulation. The first and fastest way is the | + | |

| − | + | <div style="margin:0 auto;height:405px;width:720px"> | |

| + | <center><img style="height:170%"src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/b/b5/T--Virginia--flowchart.jpg"/></center> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="p">The kennel system allows for two levels of simulation. The first and fastest way is the reductionist approach. This method disregards all files that fail any test at any point. This method is quick, but because of the variability of docking simulations, it is likely to miss key files. The exhaustive approach takes into consideration all possible mutations. After the reductionist approach is complete, all files are mutated to four mutants and re-scored. This method ensures that all possible combinations of mutations is tested, but is computationally intense.</span></p><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<span class="stitle">Output</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Output</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">After a run is complete, all files are automatically ranked and ordered by binding values (more negative is better). Once an initial ranking has be completed, the user has the option to rerun docking on the selected mutants to confirm the simulation. Should the results look bad, mutants from a lower ranking can be selected or new residues can be picked.</span></p><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Summary</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Summary</span><br> | ||

| − | <p><span class="p">Virginia iGEM designed a Linux-based protein engineering tool called MUT. This program is used to screen protein-ligand docking across possible protein mutants. It is written from a | + | <p><span class="p">Virginia iGEM designed a Linux-based protein engineering tool called MUT. This program is used to screen protein-ligand docking across possible protein mutants. It is written from a Centos shell, but is designed to be portable across distributions. MUT generates mutant structures, subjects the resultant proteins to stability testing, and ranks the results based on protein-ligand docking data. Three programs are used to accomplish this task: PyRosetta conducts computational mutagenesis, FoldX tests protein stability, and AutoDock Vina performs protein-ligand docking. All three of these programs are available for free with an educational license, and MUT is hosted on an open source site. MUT is designed to be configurable to any iGEM team’s needs. The user inputs to MUT a protein’s PDB file, residues of interest for mutation, a binding pocket, and a ligand. After the simulation runs, the program outputs a top ten list of mutant structures along with their files.</span></p><br> |

<span class="stitle">Source</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Source</span><br> | ||

| − | <a href="https:// | + | <a href="https://2016.igem.org/File:T--Virginia--UVaCode.zip" style="color:#235c81" target="_blank" class="p" color="#235c81">MUT and other code</a><br><br> |

<span class="ptitle">Pepsin Modeling</span><br><br> | <span class="ptitle">Pepsin Modeling</span><br><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Purpose</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Purpose</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">In order to determine the relative efficiency of our enzyme, we modeled another BioBrick. BBa_M1436 codes for pepsinogen, an inactive form of the cleavage enzyme pepsin. Pepsin is a nonspecific cleavage enzyme that cleaves dipeptide bonds between amino acids. Comparisons between pepsin and our enzyme may yield interesting results, specifically regarding the relationship of substrate concentration as it varies over time.</span></p><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Results</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Results</span><br> | ||

| − | <span class="stitle">Conclusions</span><br> | + | <p><span class="p">Modeling was conducted by solving for Michaelis-Menten equations in MatLab. Both Equilibrium (EA) and Quasi-Steady-State (QSSA) Approximation were used to modeling reaction rates. To determine which approach would have the most accurate results, we analysed the two error equations, <span style="height:20"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/14/T--Virginia--EquilibriumError.jpg" height="50"></span> for EA and <span><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/d/dd/T--Virginia--QuasiError.jpg" height="50"></span> for QSSA. Once analysed, it became apparent that the error term of EA would always be greater than one, while the error term of QSSA was sometimes within bounds. Future graphs do not display values that fall outside of the established error ranges.</span></p><br> |

| + | <p><span class="p">Varying concentrations of substrate and enzyme were run through the QSSA equation: <span><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/7/72/T--Virginia--QSSA.jpg" height="50"></span>. Results were visualized on two concentration ranges, 0 to 10 mM and 0 to 1 mM. This was influenced mainly by the fact that, as [E] decreased, more values fell within error bounds.</span></p><br><br> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:400"> | ||

| + | <img height="400" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/6/6b/T--Virginia--MMShort.jpg"><img height="400" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/f/f3/T--Virginia--MMLong.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="f">On the left is the short range graph of reaction rates over [S]. This graph shows a zoomed in image of the low concentration reaction rates. On the right is the wide range graph of reaction rates over [S]. As concentrations of [E] decrease the number of data points that satisfied the error bounds increase. The values shown at high concentrations on the larger range determine the bounds of possible concentrations used in the next step of modeling.</span></p><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="p">Analysis of the change in reactant concentrations over time was done using a system of four differential equations. The rate constants used were found in literature or derived from known values. The values found were: Association Constant, Catalytic Rate, and the Michaelis Constant. From there the following values were derived: Forward Rate of Reaction and Reverse Rate of Reaction. A standard [S] that could be used to compare Pepsin kinematics with literature based data regarding the our enzyme was calculated based on values found in a paper written by Nanduri et al<span class="references"><sup>ref</sup><span class="refbox"><b>Reference:</b><br>Nanduri, V.B., Goldberg, S., Johnston, R., and Patel, R.N. (2004). Cloning and expression of a novel enantioselective N-carbobenzyloxy-cleaving enzyme. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 34, 304–312. | ||

| + | </span></span>. In this study, they found a 100% cleavage rate over 48 hours at an estimated concentration of 6mM substrate - This value was calculated from an estimated mass of a Cbz-amino acid molecule.</span></p><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:300"> | ||

| + | <img height="300" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8a/T--Virginia--DiffEq.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <span class="f">The above equations were used to model reactant concentration changes over time.</span><br><br> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

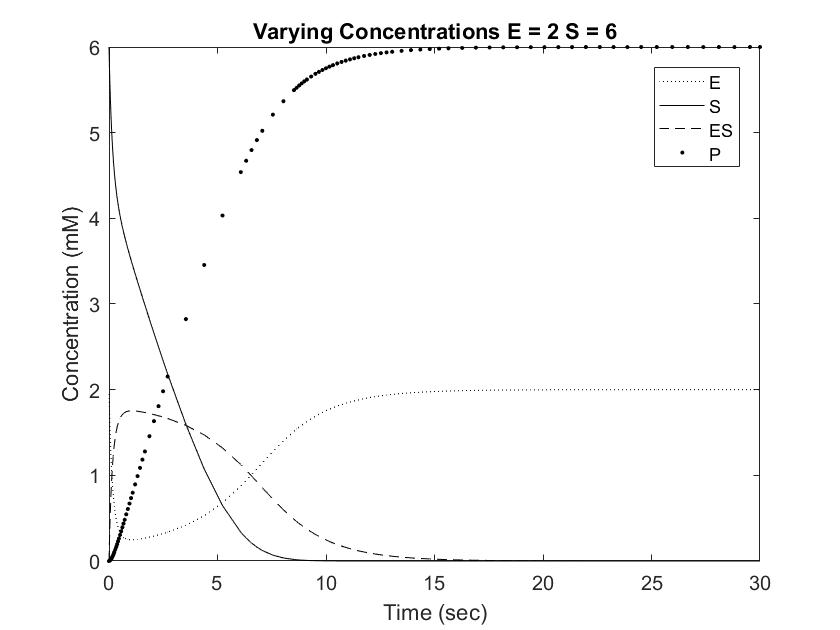

| + | <p><span class="p">In order to draw meaningful conclusions from the concentration data, [S] was set to 6mM. As shown in the Long Range Rate of Reaction graph above, possible values along [S] = 6 is limited to a range of 0 to 2 mM of enzyme. The following graphs simulate the differential equations in [E] steps of 0.5mM from 0.5 to 2.</span></p><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:300"> | ||

| + | <img height="300" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/9/9b/T--Virginia--TimeE0.5S6.jpg"><img height="300" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8a/T--Virginia--TimeE1S6.jpg"><img height="300" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/3/34/T--Virginia--TimeE1.5S6.jpg"><img height="300" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/7/71/T--Virginia--TimeE2S6.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <span class="f">Graphs depicting changes in reactant concentration over time as modeled by Michaelis differential equations. From top left to bottom right [E] increases from 0.5 to 2 in steps of 0.5mM.</span><br><br> | ||

| + | </div><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="p">Setting [S] to 6mM ensures that the rate of reaction will always be near Vmax, or the maximum rate of reaction achievable, save for situations involving very high [E]. One location where pepsin naturally occurs is in the gut at a concentration of approximately 35mM. This value is difficult to model with Michaelis approximation due to the large error at large [E], but can be estimated using very low [S] and [E]. As shown in the Short Range Rate of Reaction graph above, the values at low [S] exhibit very clean curves down to 0. Out of curiosity, we modeled value at [E] = [S] = 0.5 to visualize the relationship between the concentrations when the rate of reaction is not equal to Vmax.</span></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;height:400"> | ||

| + | <img height="400" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/a/a2/T--Virginia--TimeE0.5S0.5.jpg"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div style="text-align:center;margin:0 auto;width:50%;"> | ||

| + | <span class="f">Variables set as [E] = [S] = 0.5. This graph was one of the smoothest generated, and clearly demonstrates the relationships between the different reactants. An interesting note: Km, the concentration where V = half Vmax, is set to 0.49 in this model.</span><br><br> | ||

| + | </div><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <span class="stitle">Conclusions</span><br><br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><span class="p">Pepsin acting on a [S] of 6mM reached full conversion of substrate into product within 30 seconds. This rate is significantly faster than the Cbz-enzyme, which had recorded rates of 100% conversion over 48 hours. Furthermore, pepsin concentrations in the body are usually much higher than the tested 0.5 to 2 mM, which would result in even great rates of conversion. As shown in the graphs above, increasing [E] from 0.5 to 1 resulted in an almost doubled rate of product formation. This relationship can be expected to remain constant in the Cbz-enzyme, demonstrating that small increases in concentrations can result in dramatic changes in the concentration curve. Going forward, this information can be used to test and modify the rate of Cbz-enzyme expression in order to optimize the synthetic system.</span></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br> | ||

<span class="ptitle">Programs Used</span><br><br> | <span class="ptitle">Programs Used</span><br><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">Autodock Vina</span><br> | <span class="stitle">Autodock Vina</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">Autodock Vina is a program the performs computational protein-ligand docking. It outputs binding energy as a measure of gibbs free energy (ΔG). Autodock Vina also has other application and is capable of simulating single residue mutations.</span></p><br> | ||

| + | |||

<span class="stitle">PyRosetta</span><br> | <span class="stitle">PyRosetta</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">PyRosetta is a software suite that can perform many different simulations. In this project PyRosetta was used to model mutations on specific residues. PyRosetta is a derived from the Rosetta software suite and rewritten to work with python. It is available for free academic licences.</span></p><br> | ||

| + | |||

<span class="stitle">iGEMDOCK</span><br> | <span class="stitle">iGEMDOCK</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">iGEMDOCK is a protein-ligand docking tool meant to allow for large scale ligand screening and analysis. It takes a PDB as input along with any number of ligand files. To model the binding, iGEMDOCK uses a generic evolutionary model to iterate through possible binding conformations. After the run is complete, clusters of data are output along with residue specific energistics.</span></p><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">FoldX</span><br> | <span class="stitle">FoldX</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">FoldX measures and rates the energy present in a protein structure. It is available by academic license.</span></p><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">LigPlot</span><br> | <span class="stitle">LigPlot</span><br> | ||

| + | <p><span class="p">LigPlot generates a 2D representation of a protein-ligand interface (among other interfaces, such as protein-protein). This visualization shows both the location of residues and which residues or molecules they interact with. Molecules can be viewed with or without water present. LigPlot is also compatible with PyMol and Rasplot to create 3D visualizations of the interactions. While the 3D mode is more difficult to use, it can offer unique insights into protein-ligand interactions.</span></p><br> | ||

<span class="stitle">PyMol</span><br> | <span class="stitle">PyMol</span><br> | ||

| − | + | <p><span class="p">PyMol is a visualization tool that can display and edit proteins and molecules. It has many capabilities beyond visualization and is a powerful tool for computational analysis.</span></p><br> | |

Latest revision as of 02:03, 20 October 2016

We modeled our system in silico to select a sterically feasible protecting group and to optimize a mutant leucyl-tRNA synthetase for complementarity of its catalytic site to protected leucine, and of its editing site to leucine. To select a protecting group, the team used protein-ligand docking software to compare binding affinities of several protected leucine/synthetase complexes. To perform mutagenesis on leucyl-tRNA synthetase, an integrated software script was written in the Linux shell, with inputs including a protein to mutate, a ligand, a list of residues of interest, and binding pocket location. The script runs mutagenesis, assesses mutant protein stability, then performs ligand docking. The outputs are ranked, simulating a streamlined mutagenesis optimization algorithm. We confirmed, using CSM software suites and iGEMDOCK, that leucine-AMP and leucine-AMS yield energetically comparable binding affinities to our synthetase. Lastly, we performed Michaelis-Menten modeling for the enzyme pepsin to gauge activity in nonspecific cleavage enzymes.

Leucine Synthetase Selection

Synthetase File: 4aq7

The leucine tRNA Synthetase (LeuS) used in the following simulations was found using the RCSB Protein Data Bank. The protein, named 4aq7, is a leucyl tRNA synthetase in its aminoacylation conformation. The following is a PyMol visualization of the protein that we compiled.

AMS vs AMP

As stated in its documentation, during the characterization of 4aq7, a leucyl-adenylate analogue was used to determine the crystal structure of the protein. By analyzing the file contents in PDBest, a PDB editor software, we identified the analogue as leucyl-AMS.

We constructed six different molecules with ChemSketch in order to determine whether the analogue significantly altered the conformation of LeuS. The constructed molecules were AMS and AMP adenylations of Cbz-leu, N-methoxycarbonyl-leu, and leucine. Using a variety of protein-ligand docking software like CSM-lig, Autodock Vina and iGEMDOCK, we were able to confirm that AMS (the adenylating agent found in the literature) and AMP yield similar binding affinities to the synthetase when bound with leucine. Thus, 4aq7 represents an protein that can accurately model our system containing leucyl-AMP and LeuS.

The above figure shows select data from CSM-lig comparing Cbz-leu-AMS (Left) and Cbz-leu-AMP (Right). The predicted affinity values (3.6 and 3.4, respectively) support the hypothesis that AMS and AMP result in structurally similar conformational changes of this leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Another 4 data runs were performed and can be found in the supplementary data section, but exhibit similar results.

Protecting Group

Selection - Modeling Considerations

Several programs were used to asses the viability of the different protecting groups in our system. The main programs used for this purpose were Autodock Vina, iGEMDOCK, and CSM-Lig. The initial tests measured residue specific energistic changes between different protecting groups. However, the binding affinities for all the protecting group choices were very similar, so we chose based on a different set of criteria. These are detailed in the following figure.

Pugh chart used to score and rank possible protecting groups. Some of the criteria are practical like the cost of the protecting group and enzyme. N-carbobenzyloxy (Cbz) produced the highest relative value on our chart and was chosen as a protecting group.

Residue Selection

Literature

Half of our selected residues were intended to increase synthetase stability and reaction rates. These mutations were found by searching through current literature. We found four mutations that would improve LeuS, both through stabilization and altered editing capability. Of the four mutations, one is in the editing site while the other three are in miscellaneous locations around the protein. The editing site mutation, Thr 252, allows for the hydrolysis of Leu-tRNA, a crucial step in our overall project.22Reference:

Mursinna, R.S., Lee, K.W., Briggs, J.M., and Martinis, S.A. (2004). Molecular dissection of a critical specificity determinant within the amino acid editing domain of leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 43, 155–165.

The other stabilizing residues impact aminoacylation in two ways: through amino acid discrimination and tRNA binding21Reference:

Lue, S.W., and Kelley, S.O. (2007). A single residue in leucyl-tRNA synthetase affecting amino acid specificity and tRNA aminoacylation. Biochemistry 46, 4466–4472.

iGEMDOCK and Ligplot

To find residues of interest in the catalytic pocket, we used a combination of docking data as simulated in iGEMDOCK and of structural data visualized in Ligplot to determine additional mutational focci. iGEMDOCK is able to provide energy values for each residue by conducting an exhaustive docking search. Ligplot is capable of creating a 2D image of the binding site as detailed in the crystolography file. We selected mutations that satisfied two criteria. First, the residue had to have been shown to have a high energy during docking. Residues that returned large values in the protected leucine simulations were believed to have a high impact on the reduced viability of docking. The second criteria was location. Residues that protruded around the N terminus of leucine, the location the protecting group binds to, were thought to be possible sources of steric hindrance. A total of four residues that satisfied both criteria were selected: M40, Y41, L43 and D80.

LigPlot generates both 2D and 3D images as shown above. Energistic relationships between molecules of 4aq7 are shown in detail in the 2D representation, and conformational analysis can be conducted on the 3D image.

Final Selections

The following residues were picked for mutagenesis.

- M40

- Y41

- L43

- D80

- T252

- K186

- A293

- L570

MUT

Purpose

In order to generate and test a large list of mutants we build a software pipeline in Linux called MUT. MUT utilizes PyRosetta, Autodock Vina, and FoldX to mutate, test, and rank protein structures based on docking scores. This program was used to query for the optimal mutant structure for Cbz-Leu docking. The following is a visualization of our mutant synthetase with optimal structure.

Upon initiation, MUT asks for four main inputs: the protein pdb file that will be analysed, the residues that the program will mutate, the coordinates of the binding pocket for docking simulations, and a ligand pdb file. MUT first performs stability testing and docking to get baseline values for the future tests before it mutates the initial PDB file. At each iteration the residue is mutated to 17 other amino acids, not including Cys, Pro (as they induce kinks and are difficult to model) or itself. After mutagenesis is complete files undergo stability testing and docking to determine if the new mutant is stable and a better match for the ligand. Files that fail the tests go to the kennels. Below is a flowchart that explains the algorithm of the program.

The kennel system allows for two levels of simulation. The first and fastest way is the reductionist approach. This method disregards all files that fail any test at any point. This method is quick, but because of the variability of docking simulations, it is likely to miss key files. The exhaustive approach takes into consideration all possible mutations. After the reductionist approach is complete, all files are mutated to four mutants and re-scored. This method ensures that all possible combinations of mutations is tested, but is computationally intense.

Output

After a run is complete, all files are automatically ranked and ordered by binding values (more negative is better). Once an initial ranking has be completed, the user has the option to rerun docking on the selected mutants to confirm the simulation. Should the results look bad, mutants from a lower ranking can be selected or new residues can be picked.

Summary

Virginia iGEM designed a Linux-based protein engineering tool called MUT. This program is used to screen protein-ligand docking across possible protein mutants. It is written from a Centos shell, but is designed to be portable across distributions. MUT generates mutant structures, subjects the resultant proteins to stability testing, and ranks the results based on protein-ligand docking data. Three programs are used to accomplish this task: PyRosetta conducts computational mutagenesis, FoldX tests protein stability, and AutoDock Vina performs protein-ligand docking. All three of these programs are available for free with an educational license, and MUT is hosted on an open source site. MUT is designed to be configurable to any iGEM team’s needs. The user inputs to MUT a protein’s PDB file, residues of interest for mutation, a binding pocket, and a ligand. After the simulation runs, the program outputs a top ten list of mutant structures along with their files.

Source

MUT and other code

Pepsin Modeling

Purpose

In order to determine the relative efficiency of our enzyme, we modeled another BioBrick. BBa_M1436 codes for pepsinogen, an inactive form of the cleavage enzyme pepsin. Pepsin is a nonspecific cleavage enzyme that cleaves dipeptide bonds between amino acids. Comparisons between pepsin and our enzyme may yield interesting results, specifically regarding the relationship of substrate concentration as it varies over time.

Results

Modeling was conducted by solving for Michaelis-Menten equations in MatLab. Both Equilibrium (EA) and Quasi-Steady-State (QSSA) Approximation were used to modeling reaction rates. To determine which approach would have the most accurate results, we analysed the two error equations,  for EA and

for EA and  for QSSA. Once analysed, it became apparent that the error term of EA would always be greater than one, while the error term of QSSA was sometimes within bounds. Future graphs do not display values that fall outside of the established error ranges.

for QSSA. Once analysed, it became apparent that the error term of EA would always be greater than one, while the error term of QSSA was sometimes within bounds. Future graphs do not display values that fall outside of the established error ranges.

Varying concentrations of substrate and enzyme were run through the QSSA equation:  . Results were visualized on two concentration ranges, 0 to 10 mM and 0 to 1 mM. This was influenced mainly by the fact that, as [E] decreased, more values fell within error bounds.

. Results were visualized on two concentration ranges, 0 to 10 mM and 0 to 1 mM. This was influenced mainly by the fact that, as [E] decreased, more values fell within error bounds.

On the left is the short range graph of reaction rates over [S]. This graph shows a zoomed in image of the low concentration reaction rates. On the right is the wide range graph of reaction rates over [S]. As concentrations of [E] decrease the number of data points that satisfied the error bounds increase. The values shown at high concentrations on the larger range determine the bounds of possible concentrations used in the next step of modeling.

Analysis of the change in reactant concentrations over time was done using a system of four differential equations. The rate constants used were found in literature or derived from known values. The values found were: Association Constant, Catalytic Rate, and the Michaelis Constant. From there the following values were derived: Forward Rate of Reaction and Reverse Rate of Reaction. A standard [S] that could be used to compare Pepsin kinematics with literature based data regarding the our enzyme was calculated based on values found in a paper written by Nanduri et alrefReference:

Nanduri, V.B., Goldberg, S., Johnston, R., and Patel, R.N. (2004). Cloning and expression of a novel enantioselective N-carbobenzyloxy-cleaving enzyme. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 34, 304–312.

. In this study, they found a 100% cleavage rate over 48 hours at an estimated concentration of 6mM substrate - This value was calculated from an estimated mass of a Cbz-amino acid molecule.

In order to draw meaningful conclusions from the concentration data, [S] was set to 6mM. As shown in the Long Range Rate of Reaction graph above, possible values along [S] = 6 is limited to a range of 0 to 2 mM of enzyme. The following graphs simulate the differential equations in [E] steps of 0.5mM from 0.5 to 2.

Setting [S] to 6mM ensures that the rate of reaction will always be near Vmax, or the maximum rate of reaction achievable, save for situations involving very high [E]. One location where pepsin naturally occurs is in the gut at a concentration of approximately 35mM. This value is difficult to model with Michaelis approximation due to the large error at large [E], but can be estimated using very low [S] and [E]. As shown in the Short Range Rate of Reaction graph above, the values at low [S] exhibit very clean curves down to 0. Out of curiosity, we modeled value at [E] = [S] = 0.5 to visualize the relationship between the concentrations when the rate of reaction is not equal to Vmax.

Conclusions

Pepsin acting on a [S] of 6mM reached full conversion of substrate into product within 30 seconds. This rate is significantly faster than the Cbz-enzyme, which had recorded rates of 100% conversion over 48 hours. Furthermore, pepsin concentrations in the body are usually much higher than the tested 0.5 to 2 mM, which would result in even great rates of conversion. As shown in the graphs above, increasing [E] from 0.5 to 1 resulted in an almost doubled rate of product formation. This relationship can be expected to remain constant in the Cbz-enzyme, demonstrating that small increases in concentrations can result in dramatic changes in the concentration curve. Going forward, this information can be used to test and modify the rate of Cbz-enzyme expression in order to optimize the synthetic system.

Programs Used

Autodock Vina

Autodock Vina is a program the performs computational protein-ligand docking. It outputs binding energy as a measure of gibbs free energy (ΔG). Autodock Vina also has other application and is capable of simulating single residue mutations.

PyRosetta

PyRosetta is a software suite that can perform many different simulations. In this project PyRosetta was used to model mutations on specific residues. PyRosetta is a derived from the Rosetta software suite and rewritten to work with python. It is available for free academic licences.

iGEMDOCK

iGEMDOCK is a protein-ligand docking tool meant to allow for large scale ligand screening and analysis. It takes a PDB as input along with any number of ligand files. To model the binding, iGEMDOCK uses a generic evolutionary model to iterate through possible binding conformations. After the run is complete, clusters of data are output along with residue specific energistics.

FoldX

FoldX measures and rates the energy present in a protein structure. It is available by academic license.

LigPlot

LigPlot generates a 2D representation of a protein-ligand interface (among other interfaces, such as protein-protein). This visualization shows both the location of residues and which residues or molecules they interact with. Molecules can be viewed with or without water present. LigPlot is also compatible with PyMol and Rasplot to create 3D visualizations of the interactions. While the 3D mode is more difficult to use, it can offer unique insights into protein-ligand interactions.

PyMol

PyMol is a visualization tool that can display and edit proteins and molecules. It has many capabilities beyond visualization and is a powerful tool for computational analysis.