| Line 488: | Line 488: | ||

--> | --> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<footer id="footer" class="m-none"> | <footer id="footer" class="m-none"> | ||

Revision as of 16:13, 19 October 2016

Our Project

The human microbiome – the totality of all on and in us living microorganisms represents about 2 kilos or 4 pounds of our body weight. The world of microorganisms has by now left specialized laboratories or ancient textbooks and reached the minds of people every day. The awareness about bacteria-human interaction increases steadily.

The market for probiotics is booming, resistance against antibiotics causes losses in billions each year, not to mention human health effects. At exactly this point our project sets in. Our goal is to develop new metabolic pathways which allow our test bacteria to utilize nutrients more efficiently, to degrade toxins or to produce new antibiotics. To come straight to the point our project, called „The Last Colinator“, is dealing with selective pressure, spontaneous mutation, antibiotics resistance and the finding of new selection markers.

To reach this goal it is not enough to sit back and wait for the bacteria to do it on its own, the mills of evolution grind slowly. The driving force of evolution is stress in form of changing environment conditions as food shortage, changes in climate, natural enemies etc. Exactly those evolutionary conditions we are about to simulate.

On a culture dish – the arena – we spread out two different bacteria strains – the competitors. Each strain is equipped with certain skills which are harmful or which give it a protective shield against the competitor. That may be the ability to produce a toxin, to grow faster, to have better defense mechanisms etc. Those abilities are genetically determined by genes and therefore can be modified by molecular biologic methods. We are modifying our genes of interest in a way that they are more prone to mutagenesis by environmental stress and are thereby more effective in adapting on changing conditions.

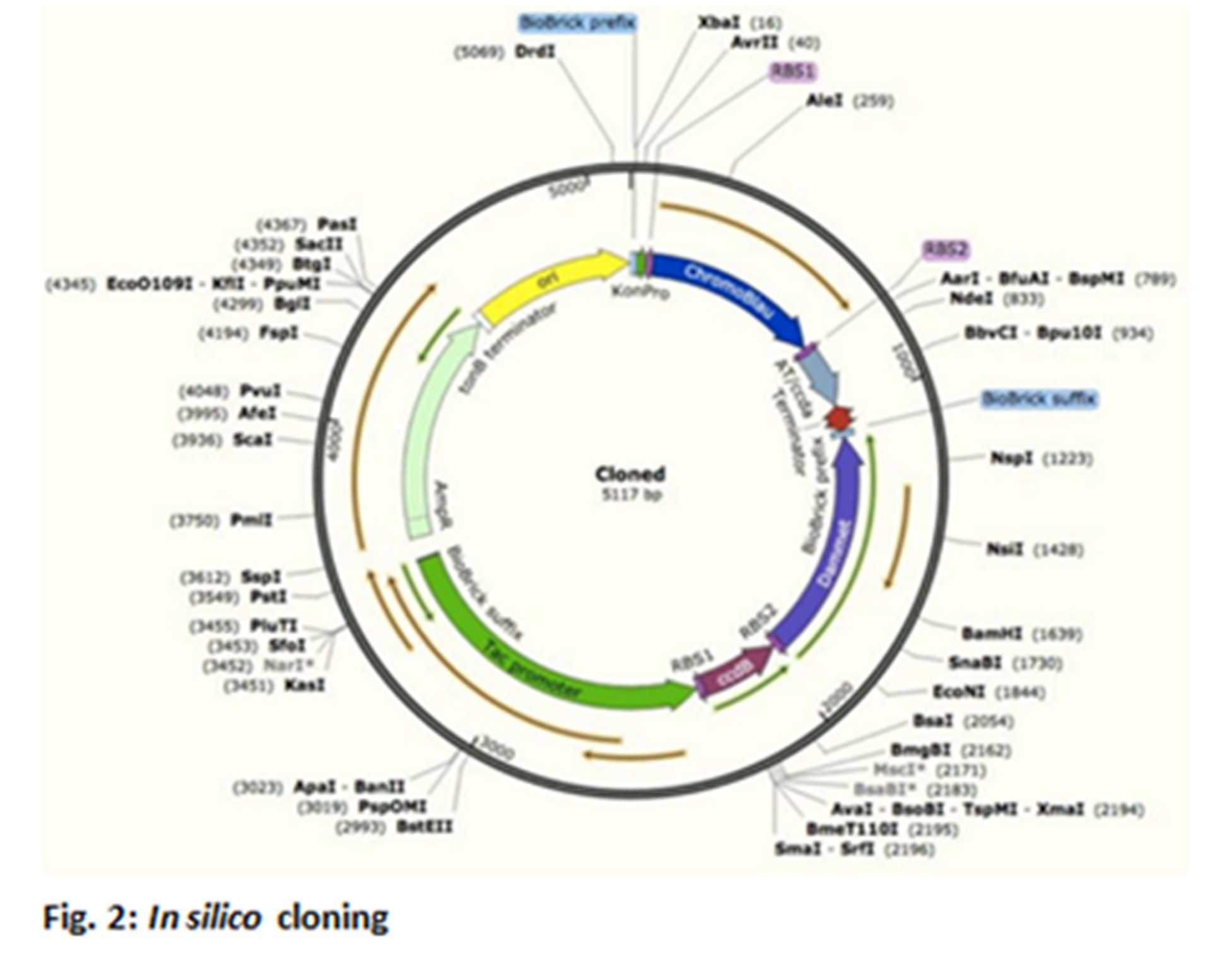

Altogether 2 different strains of Escherichia coli are used and created, different features each. Strain 1 for example comprises ccdB/ccdA genes (toxin-antitoxin-system), a DAM methylase gene and a chromoprotein gene for the visible tracking. Every strain receives its own characteristic chromoprotein genes, as well as, toxin/antitoxin genes. Every stain gets the DAM-methylase gene, though. The DAM-methylase leads to increased spontaneous mutation.

The environmental conditions like nutrient availability, temperature, pH etc. are chosen in a manner to generate highest possible stress for the bacteria, this will push evolution additionally. At the end one strain will be the sole survivor. The reason for its survival will be the fact that it developed a way or an ability to adapt faster or more efficient to those harsh life conditions. That may now be a new antibiotic, a new metabolic pathway for toxin degradation, better utilization of nutrients or many more. Furthermore, innumerable selection markers are created. These markers can later be utilized in various projects, e.g. at the creation of recombinant proteins.

ccdA/ccdB

The ccdB/ccdA toxin- antitoxin-system (TA) is a type II system. This means that the toxin is a protein and also the antitoxin is a small hydrophobic protein. By contrast, in type I systems the antitoxin is a small RNA which inhibits the expression of the toxin (PMID 19325885). If a bacterium only carries the gene of the toxin it would kill itself by interacting with the DNA gyrase (the GyrA subunit). This results in the DNA gyrase is not being able to generate and rejoin double strand breaks in the DNA, which blocks the DNA replication (PMID 19325885, PMID 10196173). Is the antitoxin, in this case ccdA, gene also present, it interacts with ccdB and inhibits the toxic effect (PMID 19325885, PMID 11454201).

MazEF

MazEF, a toxin-antitoxin locus found in E. coli and other bacteria, induces programmed cell death in response to starvation. Under normal conditions there the toxin and the antitoxin are in balance. If stress occurs, the chemically less stable antidote MazE is not as powerful anymore and the toxin can release its toxic endoribonuclease activity, leading to mRNA degradation. Even if this effect can be rescued by expression of MazE, after 6 hours in rich medium overexpression of MazF leads to programmed cell death (PubMed:8650219, PubMed:11222603). MazF-mediated cell death occurs following a number of stress conditions in a relA-dependent fashion and only when cells are in log phase; sigma factor S (rpoS) protects stationary phase cells from MazF-killing (PubMed:15150257, PubMed:19251848). Cell growth and viability are not affected when MazF and MazE are coexpressed. There are several types of toxin-antitoxin systems. MazEF is a type II toxin-antitoxin (TA) module.

read more