Contents

Vitamin A deficiency – a major global healthcare issue

Malnutrition, defined as “poor nutrition”, is caused by an inadequate diet that lacks in appropriate nutrients. Vitamin deficiencies are a serious type of malnutrition that can lead to significant morbidity through conditions such as anaemia, blindness and even death. One of the most common and serious vitamin deficiencies is that of vitamin A. It is the leading cause of preventable blindness in children and it weakens the immune system, therefore increasing the risk of severe infections [1]. An estimated 250 million preschool-aged children as well as a substantial proportion of pregnant women are deficient in this micronutrient [2].

Vitamin A (or retinol) is a fat-soluble and is involved in many different physiological functions such as vision, maintenance of differentiated epithelia, mucus secretion and reproduction. Humans tend to receive vitamin A from both animals and plant sources. Animal sources provide “preformed vitamin A” while plants provide pro-vitamin A. The main difference is that pro-vitamin A is inactive, requiring activation by the body. β-carotene, a carotenoid in plants and produced by many bacteria, is the most common type of pro-vitamin A.

Carotenoids take part in multiple functions in plants, including photoprotection and photosynthesis, as well as use in further organic compound synthesis. In humans, β-carotene is activated in the small intestine and liver by a cleavage reaction, converting it initially into retinol which can be further metabolized into the various forms of vitamin A [3].

Current treatment – high dose supplementation

Many developing countries have implemented high-dose supplementation of preformed vitamin A, administered every six months to attempt to overcome deficiencies. This is a dose large enough to be considered toxic, resulting in bone swelling, nausea/vomiting, poor appetite as well as many other symptoms. Acute toxicity is considered to occur when adults and children consume over 100 times and over 20 times the required daily allowance of Vitamin A, respectively [4] . Although the benefits of high-dose supplementation in combating vitamin A deficiency has been documented, few studies have confirmed the safety of such large doses in humans, instead focusing on how well the deficiency has been improved e.g. in curing night blindness [4].

In Africa, two trials of one dose each of 300,000 and 400,000 IU (international units) were conducted using an animal model. It was shown that, although a single large dose of preformed vitamin A increased maternal liver stores dose dependently, the theoretical contribution to the nursing infant and an actual increase in piglet liver vitamin A was not observed with increasing dosage [4]. These supplementation doses have not been studied enough to properly understand the short- and long-term effects for both the mother and the nursing infant.

Golden Rice

One of the most widely known projects to help deal with malnutrition is the Golden Rice project. Golden rice was developed to combat vitamin A deficiencies in developing countries [5]. The golden rice project goal was based around producing GM rice which contains highly elevated levels of pro-vitamin A, as normal rice lacks pro-vitamin A in the endosperm, the edible part of the plant.

The first version of Golden Rice was made by introducing a daffodil gene encoding phytoene synthase (psy) and carotene desaturase from the bacteria Pantoea ananatis. Unfortunately, a maximum level of only 1.6 μg/g of carotenoids was synthesised, and so it failed to produce pro-vitamin A in quantities large enough to have any significant effect [6]. It hypothesised that the daffodil gene was the limiting step in β-carotene accumulation and so a further iteration, dubbed Golden Rice 2.0, using the phytoene synthase gene from maize instead. This change substantially increased the carotene accumulation in a model plant system, with reports showing a maximum level of 37 μg/g of carotenoids of which 25 μg/g was β-carotene. However, the actual range varied widely, from 9 to 37 μg/g [6]. Assuming 25 μg of β-carotene per gram of rice, this would mean ingesting around 200g of rice would result in the recommended intake of β-carotene (4.8mg)

Initially Golden Rice seemed like a solution the problem of Vitamin A deficiency, however there are many doubts about the speed of degradation of pro-vitamin A after harvesting the rice and the amount of pro-vitamin A left after cooking [7]. Many environmental concerns have also been raised, as rice is a very water intensive crop [8]. Researchers believe that the traditional breeding methods have not been successful in producing rice with a high enough quantity of vitamin A, and critics have concerns around “genetic pollution”, i.e. large-scale cultivation of GM crops expressing bacterial genes that are released into the environment [9]. To avoid many of these issues, our team focused on making an alternative strategy for vitamin A supplementation that was more accessible and less environmentally demanding.

We decided to focus our efforts on producing a yogurt enriched with β-carotene, avoiding some of the issues previous projects encountered, such as large scale cultivation, degradation of pro-vitamin A through cooking and high levels of toxicity in vitamin A supplementation. To this end we introduced 3 genes from Pantoea ananatis to produce β-carotene in the lactic acid bacteria Streptococcus thermophilus, which is used in natural yogurt production. In parallel to this, we worked to further characterise S. thermophilus to further its use in synthetic biology and future iGEM projects, as well as designing a “self-inactivating mechanism” (SIM) to ensure modified bacteria do not survive in the human GI tract. Finally, we created a piece of accessible hardware designed specifically to enable people in countries most affected by vitamin A deficiency to produce their own yogurt.

Assembly of β-carotene producing biobrick

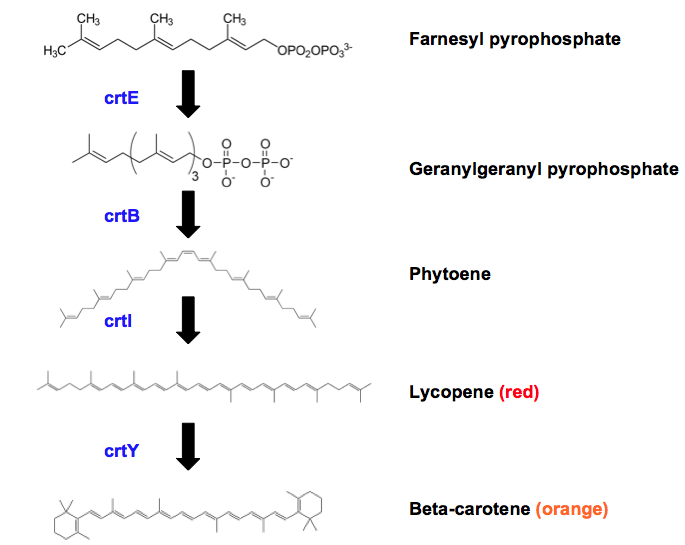

Figure 1. Schematic of final steps of β-carotene biosynthesis. Intermediates and the end product are shown in molecule format with their name to the right. Arrows represent flow of the pathway with the end product being β-carotene. Enzymes catalysing each step are shown by their abbreviated name: crtE (geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase), crtB (Phytoene synthase), crtI (Phytoene desaturase), crtY (Lycopene β-cyclase). If any molecule is a pigment, colour of said pigment is labelled next to the name of the molecule.

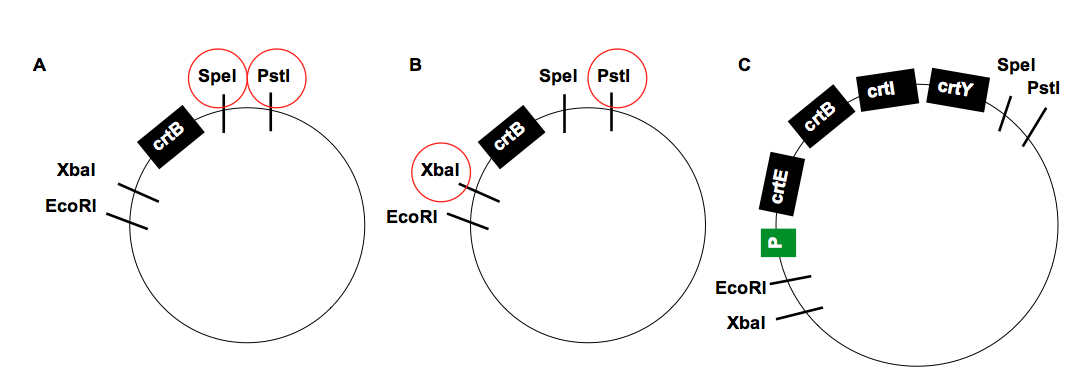

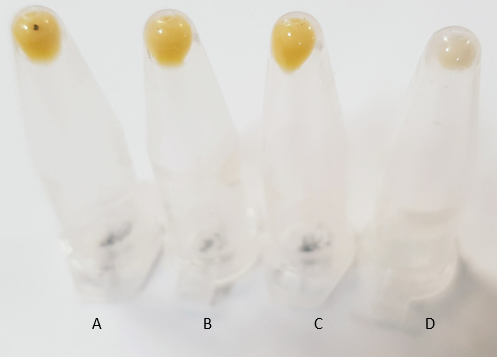

Escherichia coli has the genes necessary to synthesise farnesyl pyrophosphate, an intermediate molecule essential for the biosynthesis of β-carotene. As can be seen in Figure 1, biosynthesis of β-carotene from farnesyl pyrophosphate requires 4 additional enzymes. We have successfully assembled the biobrick K2151200 (Figure 2) containing the required enzymes and transformed this into E. coli. As expected this has caused expression of Β-carotene hence the orange coloured pellets seen in Figure 3.

Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) synthase, or crtE, catalyses a three-step reaction in which isopentenyl diphosphate is added to the product of the last step. In each step, the carbon chain is extended and a diphosphate group is lost. Phytoene synthase (crtB) then catalyses a two-step reaction that combines two GGPP molecules together and removes the diphosphate groups, creating phytoene. Phytoene desaturase (crtI) catalyses a four-step reaction to convert phytoene into lycopene. This involves adding multiple double bonds to the centre of the molecule by progressively oxidizing phytoene. Finally, lycopene β-cyclase (crtY) catalyses two rounds of cyclisation on lycopene and forms two cyclohexene-methyl groups on each end of the molecule.

As the main goal of our project is to create a yogurt enriched with β-carotene, we set out to transform this biobrick (Figure 2) into yogurt bacteria. We chose Streptococcus Thermophilus, a common lactic acid bacteria found in traditional yogurt. We decided against other lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus due to S. thermophilus being 1 of 2 bacteria species required to be in yogurt [10], as well as its ease of transformation due to Natural Competency. S. thermophilus already contains the crtE gene and so can synthesize geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) (Figure 1). We decided to keep crtE in our previously assembled biobrick as it would increase the concentration of initial GGPP in the pathway, rather than completely hijacking the supply of GGPP in S. thermophilus, which could lack efficiency and be toxic.

To simplify this process, we decided to use a known shuttle vector pMG36ET to transform both E. coli as well as S. thermophilus. This allowed us to assemble and clone our genes in E. coli and directly transform S. thermophilus for testing.

Gene order

It has been shown in the past that specific orders of the three genes at the end of the lycopene biosynthetic pathway can negatively affect growth of E. coli at both 30°C and 37°C [11]. To prevent this, we assembled our biobrick as crtEBIY (figure 2), which optimized production from the biosynthetic pathway and ensured that there would be little to no effect on growth [11].

Overexpression of this pathway has been reported in the past to be toxic to E. coli. potentially due to the hijacking of intermediates in this essential metabolic pathway. [12]. We thus decided against using solely the strongest promoters we had available to us and instead used several promoters of differing strengths. We decided to use native S. thermophilus promoters, specifically p25, p32 and pHLBA, which retain function in E. coli. This allows for transformation of E. coli and S. thermophilus using the same assembled biobrick and potentially comparing promoter activity between the 2 bacteria. While assemblying and quantifying β-carotene in E. coli we also decided to make use one of the well characterised anderson promoters J23106 and so assembled this upstream of K2151200. We did this to provide a reference point to see how effective our chosen promoters were.

Quantification

Once we had successfully transformed E. coli with our putative β-carotene constructs (Figure 3), we wanted to quantify the levels of β-carotene production from each of the promoter variants to determine whether:

A – transformation with our biobrick results in the production of β-carotene B - the promoters of varying strength cause any notable increase in this production

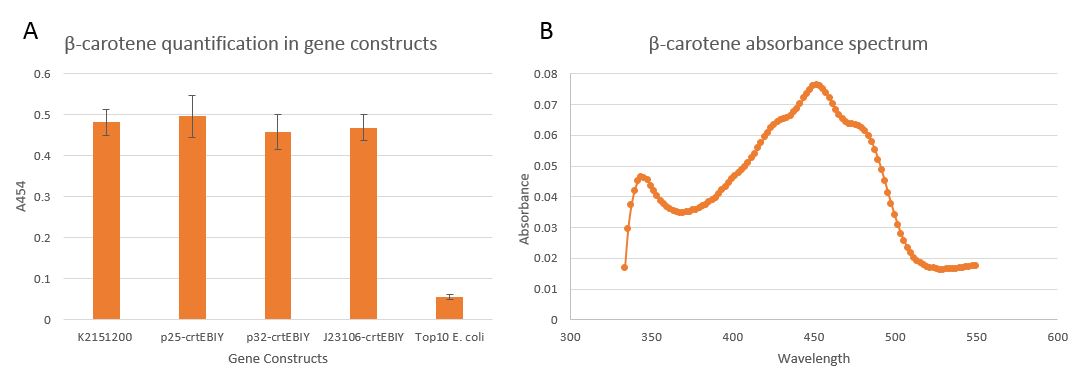

We extracted β-carotene using Acetone Extraction. The absorbance of this extraction fragment was subsequently measured at 454nm (figure 4A), the peak of β-carotene absorbance (Figure 4B).

This confirmed that K2151200 results in production β-carotene (Figure 4B) as the absorbance spectrum shows high similarity to the established absorbance spectrum of β-carotene [13].

Sadly, there appears to be no significant difference of β-carotene levels between the different promoters inserted upstream of K2151200 (Figure 4A). Our promoters could potentially still have an effect that the absorbance method is masking due to the extended preparation steps (centrifugation and manual pipetting of extracts) that could introduce bias in the measurement. In order to have a more robust answer to whether these promoters affect overall levels of β-carotene further work would need to be done in making the protocol more quantitative, for example using HPLC.

Following this quantification analysis, the constructs were sequenced, which showed that they did not possess promoter sequences upstream of K2151200 as was intended. As explained before, we chose our promoters based on their relevant strengths to increase β-carotene as much as possible. Considering this, we hypothesize that the lack of promoters is due to the stress from producing high levels of β-carotene, heavily selecting for unsuccessful ligation.

A weaker promoter of strength less than the 3 we focused on could potentially result in a notable increase in β-carotene levels, however this increase would be heavily limited due to the limited activity of the promoter. Sadly, due to time constraints, we were unable to determine whether this would be the case.

Parts submitted to the registry

We ligated crtE, crtB, crtI, and crtY together to form a composite BioBrick (BBa_K2151200) and submitted it to the registry.

References

- ↑ Stephensen, C.B. (2001). Vitamin A, infection, and immune function. Annu Rev Nutr 21, 167-192.

- ↑ WHO, 2016 http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/vad/en/

- ↑ Olson, J.A. (1964). The biosynthesis and metabolism of carotenoids and retinol (vitamin A). J Lipid Res 5, 281-299.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Penniston, K.L., and Tanumihardjo, S.A. (2006). The acute and chronic toxic effects of vitamin A. Am J Clin Nutr 83, 191-201.

- ↑ Goldenrice.org, 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Paine, J.A., Shipton, C.A., Chaggar, S., Howells, R.M., Kennedy, M.J., Vernon, G., Wright, S.Y., Hinchliffe, E., Adams, J.L., Silverstone, A.L., et al. (2005). Improving the nutritional value of Golden Rice through increased pro-vitamin A content. Nat Biotechnol 23, 482-487.

- ↑ Then, C, 2009, "The campaign for genetically modified rice is at the crossroads: A critical look at Golden Rice after nearly 10 years of development." Foodwatch.

- ↑ WWF, 2002

- ↑ Verma, 2013

- ↑ U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2009. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21, Volume 2. Part 131 Milk and Cream. Sec. 131.200 Yogurt.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Colloms, S.D., Merrick, C.A., Olorunniji, F.J., Stark, W.M., Smith, M.C., Osbourn, A., Keasling, J.D., and Rosser, S.J. (2014). Rapid metabolic pathway assembly and modification using serine integrase site-specific recombination. Nucleic Acids Res 42, e23.

- ↑ Yoon, S.H., Kim, J.E., Lee, S.H., Park, H.M., Choi, M.S., Kim, J.Y., Shin, Y.C., Keasling, J.D., and Kim, S.W. (2007). Engineering the lycopene synthetic pathway in E. coli by comparison of the carotenoid genes of Pantoea agglomerans and Pantoea ananatis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 74, 131-139

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Zang, L.Y., Sommerburg, O., and van Kuijk, F.J. (1997). Absorbance changes of carotenoids in different solvents. Free Radic Biol Med 23, 1086-1089