| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

background: #f3f4f4;} | background: #f3f4f4;} | ||

| − | + | img{width:100%} | |

| Line 424: | Line 424: | ||

<div class="col-sm-3"></div> | <div class="col-sm-3"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

<p>We characterized the his-tag after cloning it behind CRYAB. CRYAB is one of the main crystallin proteins in the human lens that aggregates to form cataracts. In our fish lens model, we observed protein aggregation after adding H2O2 (figure 2.4). </p> | <p>We characterized the his-tag after cloning it behind CRYAB. CRYAB is one of the main crystallin proteins in the human lens that aggregates to form cataracts. In our fish lens model, we observed protein aggregation after adding H2O2 (figure 2.4). </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <br><br> | |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-8"> | <div class="col-sm-8"> | ||

| Line 439: | Line 439: | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-1"></div> | <div class="col-sm-1"></div> | ||

| Line 447: | Line 448: | ||

<div class="col-sm-1"></div> | <div class="col-sm-1"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-sm-12"> | <div class="col-sm-12"> | ||

Revision as of 18:58, 19 October 2016

Description

Cataracts are the leading cause of blindness today, affecting 20 million people worldwide (World Health Organization). Half of Americans above 80 years old are affected by cataracts (National Eye Institute), and so are many animals! The National Eye Institute projects that in 30 years, the number of cataract patients will increase to 50 million (National Eye Institute).

What are Cataracts?

The lens is mostly made of proteins called crystallins. Crystallin proteins are normally soluble, which keeps the lens clear and allows light entering the eye to focus. When these proteins are damaged, they form insoluble clumps (Truscott, 2005). This causes the clouding seen in cataractous lenses, which scatters light and in turn makes vision blurry (Figure 1.1).

Cataracts can be caused by many factors, including radiation and diabetes, but the underlying cause is oxidative damage. Oxidative damage happens when unstable chemicals containing oxygen react with DNA, lipids, or proteins, disrupting cellular functions (Truscott, 2005). In the lens, crystallin proteins can be oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which is a reactive molecule produced during aerobic respiration (Giorgio et al., 2007). H₂O₂ reacts with protein residues and changes the shape of the protein. When two cysteine residues on separate proteins are oxidized by H₂O₂, for example, they can form a disulfide bond, which links these proteins together. The damaged proteins thus aggregate and form clumps in the lens (Truscott, 2005) (Figure 1.2).

In the eye, a natural antioxidant called glutathione (GSH) exists, which can convert H₂O₂ into water (Giblin, 2000). With age, however, GSH levels decrease, and oxidative damage caused by H₂O₂ increases. When there is more H₂O₂ in the lens than GSH can remove, crystallins become damaged (Figure 1.3). When GSH levels are low, H₂O₂ starts to oxidize crystallins and cause cataracts. As lens cells age, they move towards the nucleus and their GSH levels fall (Cvekl & Ashery-Padan, 2014), which may explain why the older cells in the lens nucleus are more prone to developing cataracts

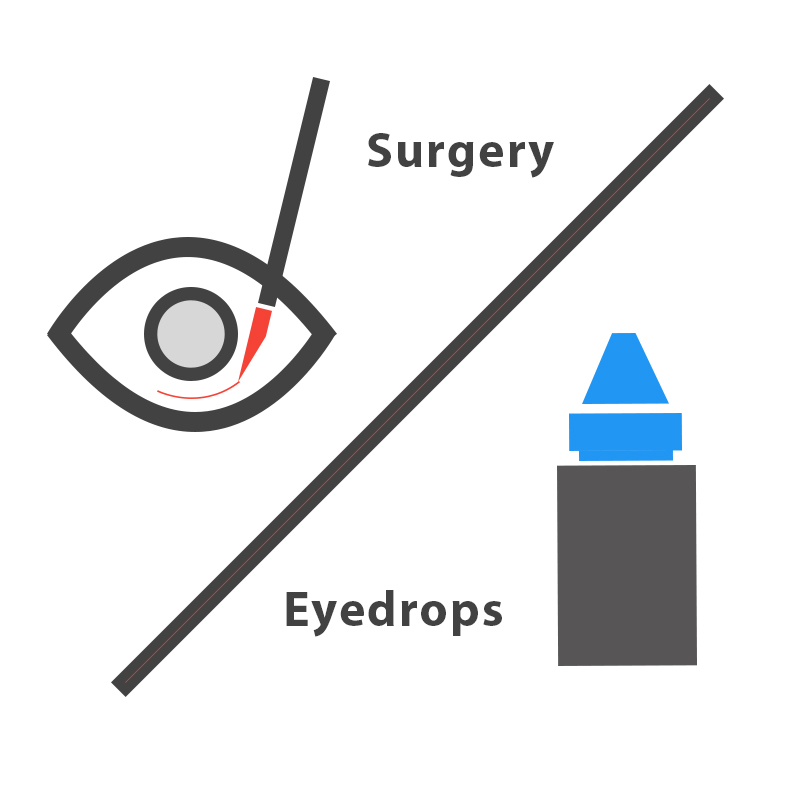

The current standard treatment for cataracts is surgery, which replaces the cloudy lens with a clear artificial lens. Surgery is effective, but like all surgeries, it is invasive and requires professional equipment and trained surgeons. These requirements add to the cost, which averages about $3,500 per eye in the US without insurance (Sigre, 2016), and is the biggest obstacle to solving cataracts worldwide. Through literature research, we found a molecule called 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC) that can reverse protein aggregation. We hope to use this as an alternative to surgery to treat cataracts.

What is our Solution?

Our goal is to develop noninvasive, easy-to-use, and affordable eyedrops to prevent and treat cataracts (Figure 1.5).

Prevention

When GSH is present, H₂O₂ can oxidize GSH instead of crystallin proteins. When GSH becomes oxidized, a disulfide bond forms between two GSH molecules, which become oxidized glutathione (GSSG). Through literature research, we found an enzyme that recycles GSSG back into GSH. This enzyme is called glutathione reductase (GSR) (Ganea & Harding, 2006). As seen in Figure 1.6, GSR (green) recycles GSSG back into GSH, so that crystallin proteins remain protected. Even though GSR exists in the lens, its levels decrease with age, which leads to the development of cataracts (Michael & Bron, 2011). Our goal is to independently produce and deliver GSR to the lens, so that cataract formation is prevented.

Treatment

We also found a molecule that can restore solubility of protein clumps and lens transparency. It is called 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC) (Makley et al., 2015). 25HC can be produced from cholesterol by the enzyme cholesterol 25-hydroxylase (CH25H) (Figure 1.7). Our goal is to independently produce and deliver CH25H to the lens, so that cataracts can be treated.

Improving a Previous Part

Our survey results show that most people are against putting any bacteria into their bodies, so we wanted to isolate the expressed proteins from the bacteria that produced them. We included a 10x-histidine tag (his-tag, Bba_K844000) in our constructs, so that we could purify the expressed proteins. We characterized the his-tag by cloning it behind CRYAB. CRYAB is a main crystallin protein in human lenses that aggregates when exposed to H2O2. In our fish lens model, when H2O2 is added, lens proteins aggregate and we see higher weight bands on a protein gel. This verifies that our model represents what occurs in cataractous human lenses.

We wanted to test if our designed CRYAB constructs would react similarly. To do this, we ran a protein gel to compare the effects of H2O2 on CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS, and confirmed that the addition of this his-tag does not change how the protein respond to oxidative stress (both CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS aggregated after adding H2O2).

After confirming the expression of CRYAB-HIS, we tested protein purification with a commercial kit. We did not succeed because the 10x his-tag binds to the column too strongly and cannot flow through. In order to figure out what went wrong, we compared the CRYAB-HIS concentrations between the lysate and flow-through and found a decrease in concentration in the flow-through, suggesting that CRYAB-HIS is indeed binding to the column. Our experiments demonstrate that 10x his-tag does not affect the protein's’ response to oxidative stress, and that when purifying protein, the length of histidine amino acids should be taken into account.

10x HISTIDINE-TAG (Bba_K844000)

Our survey results show that people are reluctant to put anything bacteria-related into their bodies, so we aimed to separate our protein products from the bacteria that produced them. As shown in figure 3.1, our constructs include a downstream 10x histidine-tag (his-tag, Bba_K844000), which allows the protein to be purified.

Our survey results show that people are reluctant to put anything bacteria-related into their bodies, so we aimed to separate our protein products from the bacteria that produced them. As shown in figure 3.1, our constructs include a downstream 10x histidine-tag (his-tag, Bba_K844000), which allows the protein to be purified.

Cloning His-tag into CRYAB Construct

We characterized the his-tag after cloning it behind CRYAB. CRYAB is one of the main crystallin proteins in the human lens that aggregates to form cataracts. In our fish lens model, we observed protein aggregation after adding H2O2 (figure 2.4).

However, we also wanted to make sure that the fish model results (figure 2.4) accurately represent what happens with human crystallin proteins, so we tested the effects of H2O2 using human CRYAB as well. Our final CRYAB construct contains a strong promoter, strong ribosome binding site, CRYAB, 10x his-tag, and a double terminator (figure 2.12). CRYAB was ordered from IDT, then using designed primers that were synthesized by Tri-I biotech, we cloned CRYAB into a Biobrick backbone. Sequencing results (Tri-I Biotech) show that the final construct was correct, and we confirmed protein expression of both CRYAB (without a poly-his tag; yellow asterisk in (figure 2.13) and CRYAB-HIS (blue asterisk in figure 2.13).

To test if human CRYAB aggregates in response to H2O2 as well, we cultured bacteria expressing both CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS. Liquid cultures were grown overnight and detergent was added to lyse the bacteria cultures. Different concentrations of H2O2 were added to the lysates and a protein gel was prepared (figure 2.13). With increasing concentrations of H2O2, we found that the addition of this his-tag does not change how the protein respond to oxidative stress (both CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS aggregated after adding H2O2). Higher bands (indicated by the blue bracket) get darker as CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS become lighter.

Protein Purification

The his-tag has 10 consecutive histidine amino acids that allow the protein to bind to nickel when it passes through a nickel column. In this way, the his-tagged proteins can be eluted to obtain purified proteins.

Since we confirmed the expression of CRYAB-HIS protein (figure 2.15), we used a commercial kit (Capturem His-tagged Purification Miniprep Kit from Clontech) to test purification using CRYAB and CRYAB-HIS. We lysed bacteria expressing GFP, CRYAB, and CRYAB-HIS and centrifuged the crude lysates to remove cell debris. Next, we passed the lysates through nickel columns to separate any his-tagged protein. To elute the his-tagged proteins, we added elution buffer with 500mM imidazole into the columns. We expected no protein in the GFP and CRYAB elutions and protein in the CRYAB-HIS elution. However, using the Nanodrop we found no protein in all three elutions.

Through literature research we learned that 6x his-tag are more commonly used and easier to elute off a column compared to a 10x his-tag (Carlsson et al., 2016). Thus, we hypothesized that our tags bound too strongly to the column. If this were the case, we should see a difference in protein concentration before and after passing his-tagged lysates through the column, whereas lysates containing untagged proteins should not change in protein concentration. After testing this hypothesis, we found that the protein concentration of CRYAB-HIS lysate decreased after passing through the column (figure 3.2), which shows that his-tagged proteins were indeed bound to the column. In contrast, the protein concentrations of CRYAB and GFP lysates remained similar. It may be useful to note that the commercial kit (Capturem His-tagged Purification Miniprep Kit from Clontech) could not be used to elute our 10x his-tag construct.

Citations

Cvekl, A., & Ashery-Padan, R. (2014). The cellular and molecular mechanisms of vertebrate lens development. Development, 141(23), 4432-4447.

Ganea, E. & Harding, J. J. (2006). Glutathione-related enzymes and the eye. Curr Eye Res., 31(1), 1–11

Giblin, F. J. (2000). Glutathione: a vital lens antioxidant. Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 16(2), 121-135.

Giorgio, M., Trinei, M., Migliaccio, E., & Pelicci, P. (2007). Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8(9), 722-8.

Makley, L. N., McMenimen, K. A., DeVree, B. T., Goldman, J. W., McGlasson, B. N., Rajagopal, P., Dunyak, B.M., McQuade, T.J., Thompson, A.D., Sunahara, R., Klevit, R.E., Andley, U.P., and Gestwicki, J.E. (2015). Pharmacological chaperone for α-crystallin partially restores transparency in cataract models. Science, 350(6261), 674-677.

Michael, R., & Bron, A. J. (2011). The ageing lens and cataract: a model of normal and pathological ageing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 366(1568), 1278-1292.

National Eye Institute | Cataracts. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/cataract

Segre L (2016, Sept. 21). Cataract surgery cost. Retrieved from http://www.allaboutvision.com/conditions/cataract-surgery-cost.htm

Truscott, RJ (2005). Age-related nuclear cataract-oxidation is the key. Exp Eye Res., 80(5): 709-25.

World Health Organization | Priority eye diseases. (n.d.). Retrieved October 03, 2016, from http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/priority/en/index1.html

×

Zoom out to see animation.

Your screen resolution is too low unless you zoom out