The development of an oral vaccine against leishmaniasis using our Limitless Lactis protein-producing platform

We have used iRFP to demonstrate that our L.lactis strain could be used to deliver proteins to the cytosol of antigen-presenting cells. Thus, we decided to devise an application for this protein delivery platform.

Vaccination is a possible application of this platform, so we decided to use it to develop a vaccine. Through our human practices work, we identified leishmaniasis as a neglected tropical disease against which an oral vaccination is required.

The problem:

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by the intracellular parasite leishmania, of which there are over 20 species.

There are three main types of leishmaniasis:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis - This is the most common form. It is characterised by skin lesions, which can be open or closed sores. They typically progress from papules to nodular plaques and then to open lesions with a raised border and a central crater. It can heal eventually, but usually leads to scarring. The lesion can become infected by bacteria, leading to secondary infections.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis - This is the least common form. The parasites can spread from the skin to the mucous membranes such as the mouth and the nose and cause sores.

Visceral leishmaniasis - This is the most severe form of the disease. It is also known as kala-azar, black fever and Dumdum fever. If left untreated, severe cases of visceral leishmaniasis are usually fatal. It is characterised by fever, weight loss, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (an enlargement of the liver and spleen respectively).

It is spread by the sandfly, Lutzomyia longipalpis. When the sandfly takes a blood meal from a human, it transmits the protozoa to the blood of the human. The lifecycle of leishmaniasis is shown below:

Figure 1: The lifecycle of leishmaniasis

Source: www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/biology.html

The solution:

We identified salivary proteins of the sandflies as a possible target for vaccination. Salivary proteins play an important role in the establishment of the leishmania infection in the host. While the full role in salivary proteins in the establishment of the disease in the host has not yet been elucidated, it is known that one role is to bind to and remove small molecule mediators of hemostasis and inflammation, such as serotonin, histamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline. These high-affinity ligand binding proteins are known as kratagonists. Some of these so-called “yellow” proteins have also been shown to be immunogenic, including our protein of interest, LJM11. (Xu, Xueqing et al., 2011)

LJM11 is a kratagonist. Serotonin binds to LJM11 via hydrogen bonds between its amino group and the side chains of Asn-342 and Thr-327 as well as with the carbonyl oxygen of Phe-344. (Xu, Xueqing et al., 2011). LJM11 is found in the saliva of the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis, the vector for species of leishmaniasis such as Leishmania major and Leishmania infantum. The features of these species are summarised below:

| # | Species | Vector | Old/New World | Form of leishmaniasis caused |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L. major | Lutzomyia longipalpis | New | Cutaneous |

| 2 | L. infantum chagasi | Lutzomyia longipalpis | New | Visceral |

LJM11 is able to induce an immune response against the pathogen, but this ability is not linked to its serotonin-binding ability. Due to the positive charge on the surface of its top face, it is more effectively phagocytosed by macrophages and dendritic cells than if it were neutral or negatively charged. (Xu, Xueqing et al., 2011) Thus, an immune response can be mounted against it. Indeed, this protein has been shown to confer protective immunity against L. major transmitted by the sandfly in mouse experiments, conferring ulcer-free protection. This ability was first shown when administered without adjuvant by intradermal injection (Gomes, Regis et al.2012) It was then shown when a Listeria monocytogenes based vaccine which secreted this protein was administered by a number of parenteral routes, with the greatest protection being provided when administered intravenously. (Abi Abdallah, Delbert S. et al., 2014).

On our visit to Honduras, we identified the need for an oral vaccination for leishmaniasis. Thus, we had to ensure that our platform would be capable of eliciting an immune response when administered orally.In the gut, the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) contains lymphoid follicles forming Peyer’s patches. The Peyer’s patches are surrounded by a follicle-associated epithelium that which contain M-cells. These M-cells can transport antigens and bacteria towards the underlying immune cells via a process called transcytosis, which can lead to either an immune response or tolerance. (Jung et al., 2010) This is where our oral vaccination against leishmaniasis will be aimed.

The immune response to LJM11 is both humoral and cell-mediated. The humoral response is characterised by the presence of antibodies specific to LJM11, with a high IgG2a:IgG1 ratio (Gomes, Regis et al.2012). However, the most important aspect of the immune response to LJM11 is a strong of T-helper cell type 1 (TH1) response, characterised by delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH). (Scott and Novais, 2016)The protection is correlated with CD4+, interferon gamma+ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor alpha positive/negative (TNFα+/-), interleukin-10 negative (IL-10-) cells. Thus, IFN-γ is the most important part of the response; it plays a vital role in activating macrophages to kill the leishmania.

An IgG2a antibody The various roles of IFN-γ

Workflow:

The following was carried out:

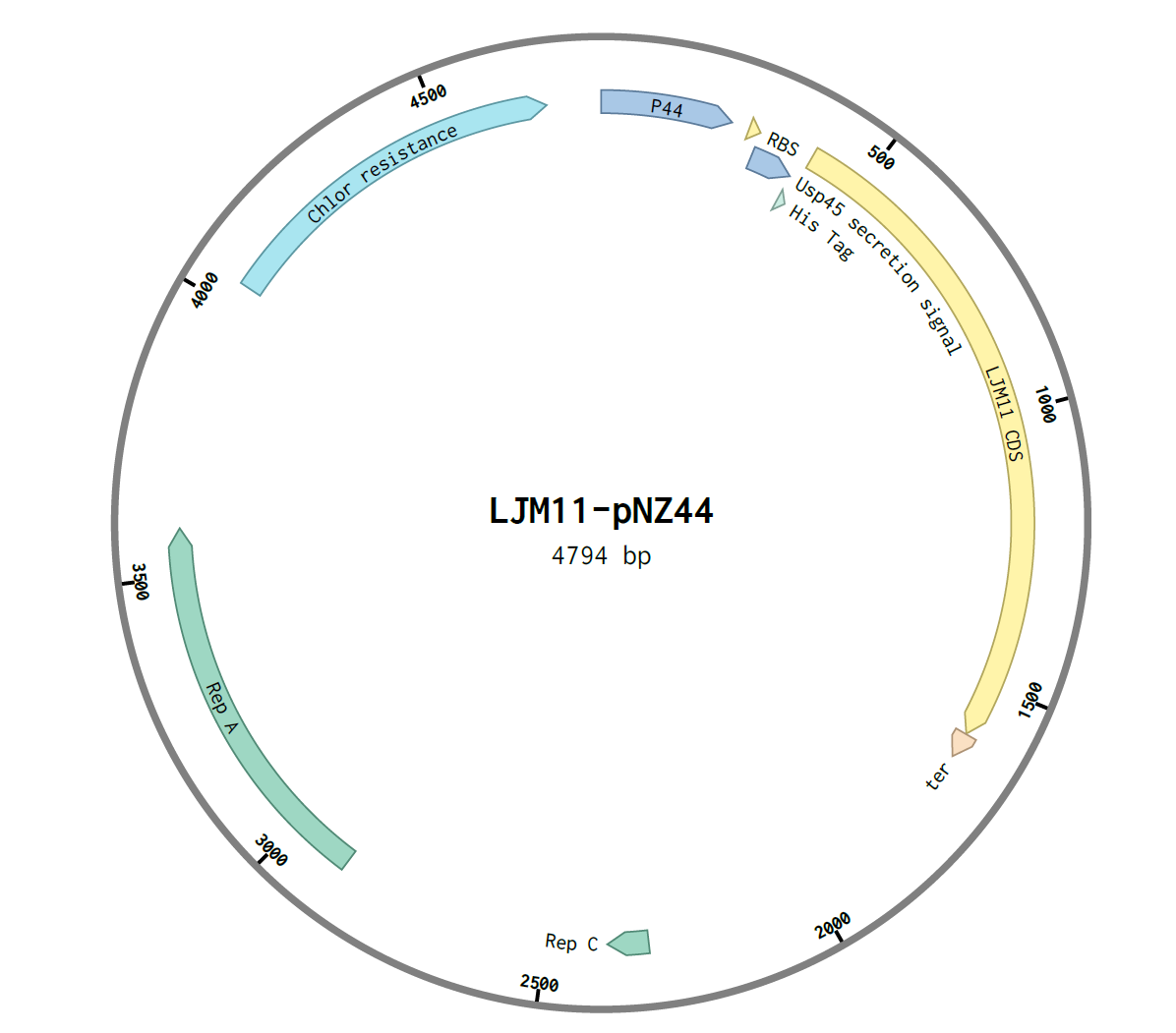

- A pNZ44-USP45-His-LJM11 construct was created by Gibson assembly

- This was transformed into E.coli C2987I cells by heat shock

- This was then transformed into L.lactis subsp. cremoris by electroporation

- The secretion of the protein was shown by SDS-PAGE gel

Assembly of construct:

The G-block with overlapping Gibson ends for the shuttle vector pNZ44 was ordered from IDT:

The overlapping regions were 28bp on the 5’ end of the G-block and 24bp on the 3’ end of the G-block. pNZ44 was digested with the single-cutting enzyme XbaI and purified using a ThermoScientific GeneJET PCR Purification Kit and its concentration determined using a nanodrop.

The genes were then assembled using NEB E5520S HiFi DNA Assembly Kit. An insert:plasmid ratio of 3:1 was used. The following construct was obtained:

After assembly, the construct was transformed into E.coli C2987I cells by the heat-shock method and 100μL was plated on two chloramphenicol LB agar plates, A and B. They were incubated overnight at 37℃. Six colonies were observed on plate A and one colony in plate B, and thus were labelled A1-6 and B1.

Colonies were screened using colony PCR. The primers used were: forward primer for USP45, reverse primer for pNZ44. The expected amplicon was ~300bp. PCR was carried out using 5x HOT FIREPol® Blend Master Mix Ready to Load. After PCR an agarose gel was run and the following was observed:

Following this, LJM11 colony A3 was sequenced by MWG and the sequence was confirmed as correct. The construct was transformed into L.lactis by electroporation. GM17 plates containing chloramphenicol were used

The secretion of the protein was then shown. Overnights of the colonies of pNZ44-LJM11 L.lactis were carried out using GM17 broth containing chloramphenicol. The cells were spun down and the supernatant removed. The supernatant was concentrated using an Amicon filter. Amicon filters contain pores which allow proteins less than 30kDa in size to pass through. Proteins greater than 30kDa are retained in the filter. As our protein is 46kDa in size, it was retained in the filter.

The concentrated supernatant was run on an SDS PAGE gel. The presence of a protein of the correct size (46kDa) was observed, confirming the secretion of our protein.

Western blot was attempted but was not successful. The antibody did not bind. A lack of time prevented us from successfully troubleshooting our Western blot. Other tags could have been tried such as GST or Flag. Due to the lack of time, we were unable to investigate these. The his tag may have been unable to be bound by antibody because of the protein’s tertiary structure.

Over the course of this project, we were able to identify and develop a possible therapeutic application of our protein-producing L. lactis platform in the real world. We have also discovered the implications of this vaccine from a variety of different angles, which we explored and integrated into our project.

Other Applications

Mesothelin

Background

One of today’s most promising cancer treatments is cancer vaccines-the administration of tumour specific antigens (TSAs-proteins expressed specifically by tumour cells) or TAAs (Tumour Associated Antigens-proteins expressed by tumour cells but that can also be expressed by normal cells), with the aim of eliciting an immune response against the malignant cells. Since its conception in the 50s, this idea has gained a significant amount of momentum and has had quite a degree of success, with one therapeutic cancer vaccine already being used in clinical practice (sipuleucel-T), and several others in phase II/III clinical trials.(1) Cancer vaccines have several potential benefits over traditional cancer treatments (such as small molecule inhibitors), including fewer side effects and the need for only a single or a few administrations of the therapeutic agent.(1). In light of this, our group decided that a TAA would be an excellent candidate to work with in the development of our L.lactis platform.

The TAA we decided to work with was mesothelin. This is a cell surface protein which is normally expressed in small amounts in the mesothelial lining of the pleura, pericardium and peritoneum.(2) However, it is over expressed in ovarian, pancreatic, mesothelial and lung cancers, making it a potentially useful target for cancer immunotherapy.(2) While its physiological function is largely unknown, it is thought to be involved in tumour cell adhesion and metastasis, through binding to another TAA called MUC16.(3) Results of studies investigating the utility of mesothelin targeted therapy to date have been promising. Three such therapies have been investigated, with two currently in phase I clinical trials and another entering into phase II clinical trials.(2) Furthermore, the molecular properties of mesothelin seemed to suit our project very well. At 1877 base pairs, it is small enough to be ligated efficiently into our expression vector, pNZ44. Furthermore, online software tools didn’t show our construct to have any significant secondary structure, making it suitable for transformation into and expression in L.lactis. Thus, mesothelin seemed to satisfy all the criteria for use in our project.

Construct

Difficulties in cloning led to extended troubleshooting of this sub-project and instead of pursuing working on this area, our team decided to focus more so on the other subprojects.

CRISPR

In addition to the various other potential applications of our Limitless lactis delivery system, we intended to show its ability to utilise CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) to modify the genome or alter gene expression. CRISPR, although still in its infancy in its use as a genome editing tool, continues to surprise us with its signs of unprecedented potential and ability to transform molecular biology. The CRISPR system is derived from the bacterial immune system, where it is used by the prokaryote to destroy viral DNA. CRISPR consists of 2 components: a nuclease (Cas9), which acts as a scissors cutting both strand of the DNA, and a ~20nt sgRNA molecule, which acts as a sat nav, finding the specific nucleotide sequence to cut. The Cas9 gene sequence can also be altered slightly to express a nuclease dead Cas9 (dCas9) which can block the transcription of the specific gene rather than excising it. This system can easily be engineered to alter/disrupt any gene we desire with extreme precision, hence vastly improving the speed and capabilities of genetic engineering.

Although we were unable to demonstrate the use of CRISPR in our L. lactis strain due to having to troubleshoot the cloning of the construct and the intended subsequent experiments proving troublesome to get correct. Our preliminary work with the system will be followed up in the future. We were unable to do the troubleshooting experiments that we would have liked due to lack of time but are currently planning to do them following iGEM and continue the work of the team.

References:

Abi Abdallah, Delbert S. et al. “A Listeria Monocytogenes-Based Vaccine That Secretes Sand Fly Salivary Protein LJM11 Confers Long-Term Protection against Vector-Transmitted Leishmania Major.” Ed. J. L. Flynn. Infection and Immunity 82.7 (2014): 2736–2745. PMC. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Gomes, Regis et al. “Immunity to Sand Fly Salivary Protein LJM11 Modulates Host Response to Vector-Transmitted Leishmania Conferring Ulcer-Free Protection.” The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 132.12 (2012): 2735–2743. PMC. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

Jung, Camille, Jean-Pierre Hugot, and Frédérick Barreau. “Peyer’s Patches: The Immune Sensors of the Intestine.” International Journal of Inflammation2010 (2010): 823710. PMC. Web. 18 Oct. 2016.

Scott, P. and Novais, F.O. (2016) ‘Cutaneous leishmaniasis: immune responses in protection and pathogenesis’, 16(9), pp. 581–592.

Xu, Xueqing et al. “Structure and Function of a ‘Yellow’ Protein from Saliva of the Sand Fly Lutzomyia Longipalpis that Confers Protective Immunity against Leishmania Major Infection.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286.37 (2011): 32383–32393. PMC. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.