Kevinr9525 (Talk | contribs) |

Kevinr9525 (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

<img class="img-responsive" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/1f/T--UCC_Ireland--ls5.gif" style="width: 50%;"> | <img class="img-responsive" src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/1f/T--UCC_Ireland--ls5.gif" style="width: 50%;"> | ||

| − | <p> Source:<a href="www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/biology.html</a> </p> | + | <p> Source:<a href="www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/biology.html>www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/biology.html</a> </p> |

<h4>The solution:</h4> <br> | <h4>The solution:</h4> <br> | ||

Revision as of 10:03, 19 October 2016

The development of an oral vaccine against leishmaniasis using our Limitless Lactis protein-producing platform

We have used iRFP to demonstrate that our L.lactis strain could be used to deliver proteins to the cytosol of antigen-presenting cells. Thus, we decided to devise an application for this protein delivery platform.

Vaccination is a possible application of this platform, so we decided to use it to develop a vaccine. Through our human practices work, we identified leishmaniasis as a neglected tropical disease against which an oral vaccination is required.

The problem:

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by the intracellular parasite leishmania, of which there are over 20 species.

There are three main types of leishmaniasis:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis - This is the most common form. It is characterised by skin lesions, which can be open or closed sores. They typically progress from papules to nodular plaques and then to open lesions with a raised border and a central crater. It can heal eventually, but usually leads to scarring. The lesion can become infected by bacteria, leading to secondary infections.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis - This is the least common form. The parasites can spread from the skin to the mucous membranes such as the mouth and the nose and cause sores.

Visceral leishmaniasis - This is the most severe form of the disease. It is also known as kala-azar, black fever and Dumdum fever. If left untreated, severe cases of visceral leishmaniasis are usually fatal. It is characterised by fever, weight loss, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (an enlargement of the liver and spleen respectively).

It is spread by the sandfly, Lutzomyia longipalpis. When the sandfly takes a blood meal from a human, it transmits the protozoa to the blood of the human. The lifecycle of leishmaniasis is shown below:

Figure 1: The lifecycle of leishmaniasis

The following was carried out:

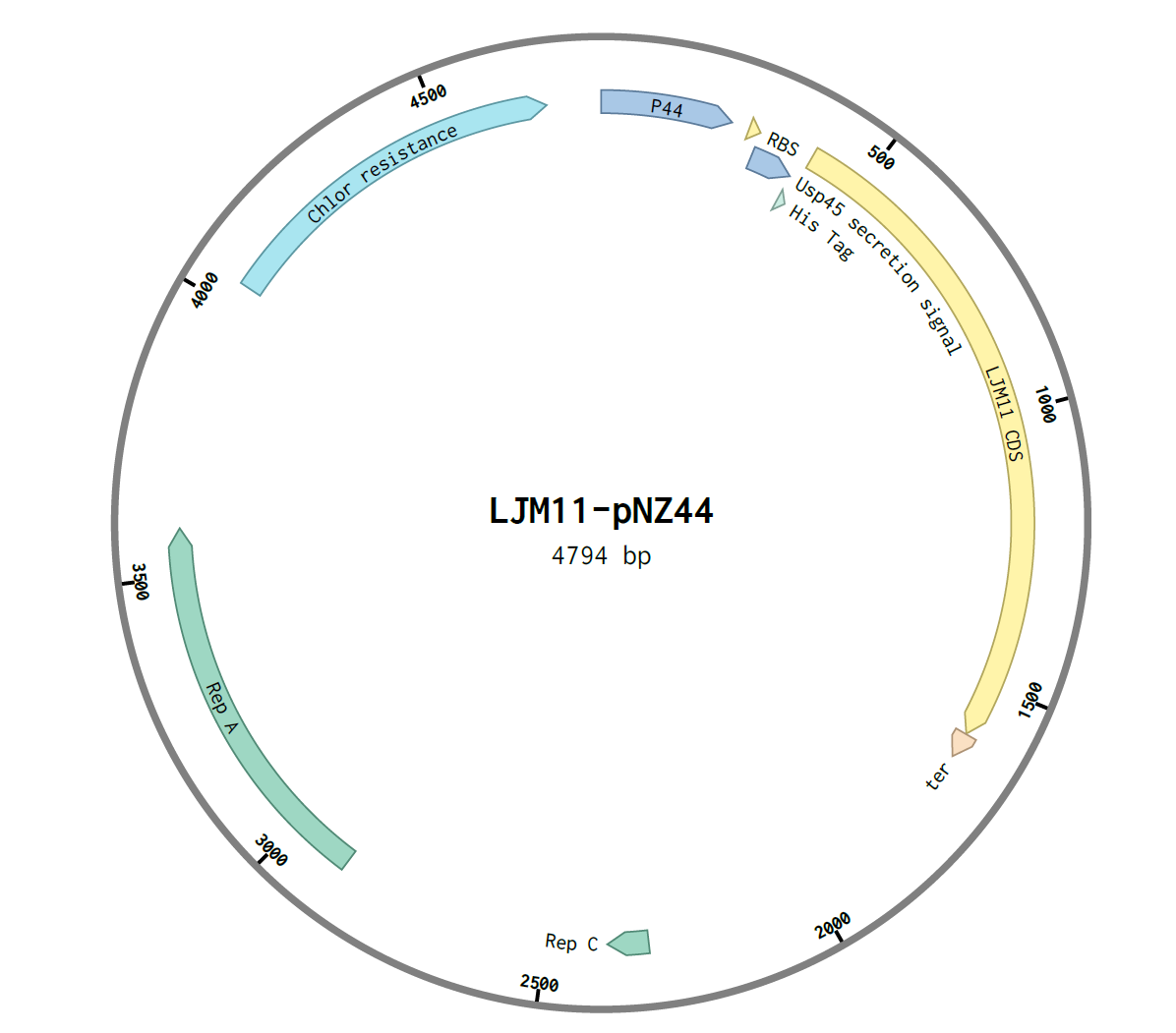

- A pNZ44-USP45-His-LJM11 construct was created by Gibson assembly

- This was transformed into E.coli C2987I cells by heat shock

- This was then transformed into L.lactis subsp. cremoris by electroporation

- The secretion of the protein was shown by SDS-PAGE gel

Assembly of construct:

The G-block with overlapping Gibson ends for the shuttle vector pNZ44 was ordered from IDT:

The overlapping regions were 28bp on the 5’ end of the G-block and 24bp on the 3’ end of the G-block. pNZ44 was digested with the single-cutting enzyme XbaI and purified using a ThermoScientific GeneJET PCR Purification Kit and its concentration determined using a nanodrop.

The genes were then assembled using NEB E5520S HiFi DNA Assembly Kit. An insert:plasmid ratio of 3:1 was used. The following construct was obtained:

After assembly, the construct was transformed into E.coli C2987I cells by the heat-shock method and 100μL was plated on two chloramphenicol LB agar plates, A and B. They were incubated overnight at 37℃. Six colonies were observed on plate A and one colony in plate B, and thus were labelled A1-6 and B1.

Colonies were screened using colony PCR. The primers used were: forward primer for USP45, reverse primer for pNZ44. The expected amplicon was ~300bp. PCR was carried out using 5x HOT FIREPol® Blend Master Mix Ready to Load. After PCR an agarose gel was run and the following was observed:

Following this, LJM11 colony A3 was sequenced by MWG and the sequence was confirmed as correct. The construct was transformed into L.lactis by electroporation. GM17 plates containing chloramphenicol were used

The secretion of the protein was then shown. Overnights of the colonies of pNZ44-LJM11 L.lactis were carried out using GM17 broth containing chloramphenicol. The cells were spun down and the supernatant removed. The supernatant was concentrated using an Amicon filter. Amicon filters contain pores which allow proteins less than 30kDa in size to pass through. Proteins greater than 30kDa are retained in the filter. As our protein is 46kDa in size, it was retained in the filter.

The concentrated supernatant was run on an SDS PAGE gel. The presence of a protein of the correct size (46kDa) was observed, confirming the secretion of our protein.

Western blot was attempted but was not successful. The antibody did not bind. A lack of time prevented us from successfully troubleshooting our Western blot. Other tags could have been tried such as GST or Flag. Due to the lack of time, we were unable to investigate these. The his tag may have been unable to be bound by antibody because of the protein’s tertiary structure.

Over the course of this project, we were able to identify and develop a possible therapeutic application of our protein-producing L. lactis platform in the real world. We have also discovered the implications of this vaccine from a variety of different angles, which we explored and integrated into our project.

References:

Abi Abdallah, Delbert S. et al. “A Listeria Monocytogenes-Based Vaccine That Secretes Sand Fly Salivary Protein LJM11 Confers Long-Term Protection against Vector-Transmitted Leishmania Major.” Ed. J. L. Flynn. Infection and Immunity 82.7 (2014): 2736–2745. PMC. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Gomes, Regis et al. “Immunity to Sand Fly Salivary Protein LJM11 Modulates Host Response to Vector-Transmitted Leishmania Conferring Ulcer-Free Protection.” The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 132.12 (2012): 2735–2743. PMC. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

Jung, Camille, Jean-Pierre Hugot, and Frédérick Barreau. “Peyer’s Patches: The Immune Sensors of the Intestine.” International Journal of Inflammation2010 (2010): 823710. PMC. Web. 18 Oct. 2016.

Scott, P. and Novais, F.O. (2016) ‘Cutaneous leishmaniasis: immune responses in protection and pathogenesis’, 16(9), pp. 581–592.

Xu, Xueqing et al. “Structure and Function of a ‘Yellow’ Protein from Saliva of the Sand Fly Lutzomyia Longipalpis that Confers Protective Immunity against Leishmania Major Infection.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286.37 (2011): 32383–32393. PMC. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.