Fra terenz (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 319: | Line 319: | ||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

<div class="col-md-10 col-md-offset-1"> | <div class="col-md-10 col-md-offset-1"> | ||

| − | <h2 class="animate-box text-center">Characterization of CYC1 promoter by scRNAs: plan for the future</h2> | + | <h2 id = "CYC" class="animate-box text-center">Characterization of CYC1 promoter by scRNAs: plan for the future</h2> |

<div class="spacer h20"></div> | <div class="spacer h20"></div> | ||

<hr class="animate-box"/> | <hr class="animate-box"/> | ||

| Line 327: | Line 327: | ||

<p class="sub-lead"> | <p class="sub-lead"> | ||

Here we resume all the data collected about the regulatory elements of CYC1 promoter. | Here we resume all the data collected about the regulatory elements of CYC1 promoter. | ||

| + | |||

</p> | </p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 02:56, 20 October 2016

Results

Our project aimed to build modular biological logic gates in yeast, by exploiting a dCas9-based system. Therefore, we decided to simulate a biological ON/OFF state, like in an electrical system where the ON state corresponds to the current flow and the OFF state to the absence of current. To achieve this goal, we assembled fundamental parts for the control of gene expression: an activator for the ON state and a repressor for the OFF state. We used Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) as a reporter gene to assess the correct behaviour of our basic effector modules. Measurements were taken by performing overnight photospectroscopy (or, overnight plate reader) and using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS).

- Cloning all the plasmids needed

- Activation of CYC1 promoter

- Repression of Tef1 promoter

- Inducible NOT gate (CYC1p)

- Repression prevails over activation (CYC1p)

- Include the activation part in a more robust NOT gate

- Other gates

Activation of CYC1 promoter the ON state

Scaffold RNA based modules seem to be more efficient than both CRISPRa/i and dCas9 fused systems; namely, MS2 scRNA recruitment of VP64 strongly activates gene expression in eukaryotic cells (Zalatan et al., 2015).

Since the CYC1 promoter (BBa_K1723022) activation has never been tested before using the scaffold system (scCYC1_c3, BBa_K1941001), we decided to assemble all the parts required to induce its gene expression (Fig. 1A).

The first measurement was done using an overnight plate-reader (Fig. 1B). We observed that cells transfected with all the components of the activation module express two times more GFP than the negative control. To confirm these results further, we performed another experiment using FACS (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1A. Activation design. scCYC1_c3 construct with MS2 recruits its cognate RNA-binding protein MCP fused to VP64 and targets the region c3 of CYC1 promoter. dCas9 allows the activator complex to move and bind the c3 sequence, then the activator domain VP64 stimulates gene expression.

Figure 1B. Activation of CYC1 promoter in yeasts by scCYC1_c3 construct, histogram of FACS results (Relative Fluorescence). The same strains as used in the experiment shown in figure 2B) were grown overnight in 2% glucose selective medium and the GFP fluorescence was measured with FACS (LSRII Snoopy). The data were normalized to report to the basal level, which corresponds to cells single-transfected with the plasmid carrying CYC1-GFP. As we can see in Fig. 1C, the fluorescence emitted upon activation is more than two times higher than the basal level.

Figure 1C. Overnight Tecan micro-plate reader (RFU/OD). Cells were grown overnight in 2% glucose in a 96 well plate. Every 5 min, growth and GFP fluorescence were measured using OD390 values and relative fluorescence units (RFU), respectively. Experiments were performed in triplicate. The blue line corresponds to not-transfected cells (W303), which don’t express GFP. The red line represents cells single-transfected with CYC1-GFP. Lastly, the green line represents cells additionally transfected with all the activation components: the scRNA MS2, the fused activator protein MCP-VP64 and dCas9. Activation exceeds more than two times the basal level of GFP expression. We can also suppose that incubating cells longer (e.g. until an OD390 of 1.4-1.5) would induce an even stronger activation.

First scRNA repression in yeast Tef1 promoter

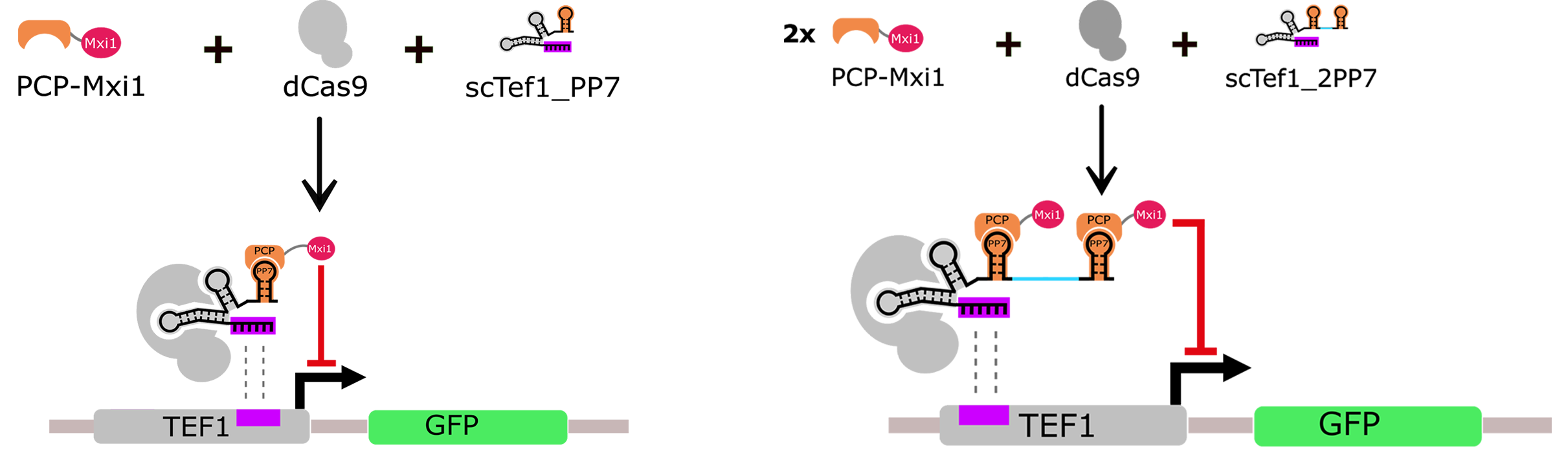

The endogenous promoter Tef1 was shown to be repressed in yeast by fusing dCas9 with the strong chromatin remodeler Mxi1 (Gilbert et al., 2013). In light of this finding, we designed a repressor system based on a scRNA carrying the well-characterized viral RNA sequence PP7 (scTef1_PP7, BBa_K1941001). The sequence PP7 is recognized by the PCP RNA-binding protein (Chao et al., 2007) at which we fused the transcriptional repressor domain Mxi1 (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we made another version of scTef1_PP7, equipped with an additional hairpin that recruits a second repressor module (scTef1_2PP7, BBa_K1941002).

To our knowledge, we are the first to show that repression in yeast could be also achieved using scaffold recruiter elements. The results obtained confirmed that our system behaved like a functional transcriptional repressor module (Fig. 2). Additionally, we observed that scTef1_2PP7 did not repress Tef1 promoter more efficiently than scTef1_PP7. We therefore used the simpler system with the single hairpin PP7 in further experiments.

Figure 2A. Repression design of Tef1 promoter. The hairpins PP7 or 2PP7 recruit the RNA binding domain PCP fused with the transcriptional repressor protein Mxi1. Then, dCas9 carries the repressor complex to the promoter Tef1, guided by the recognition sequence of the scRNA. scTef1_2PP7 was tested to reinforce the repression. However, no significant difference in the level of GFP expression had been observed between the two constructs.

Figure 2B. Relative fluorescence histogram. GFP levels were measured using FACS after overnight cells growth. A bar graph shows fluorescence intensity of a strain transformed with three different plasmids carrying the following parts: Tef1-GFP, scTef1_PP7 or scTef1_2PP7, dCas9 and the fused repressor protein PCP-Mxi1 (BBa_K1941000). The data were normalized to report to the basal level: cells that have been integrated with a single plasmid carrying GFP under Tef1 promoter. A repression of 70 % GFP expression was noticeable with both constructs.

Figure 2C. Flow cytometry data (LSRII Snoopy) to quantify the level of GFP expression under the control of Tef1 promoter. In light blue, a population of cells that express dCas9, scTef1_PP7 and PCP-Mxi1. In grey, a population that express basal level of GFP under the control of Tef1 promoter.

Proof of concept: the inducible NOT gate

After successful repression of Tef1 promoter using scTef1_PP7 (Fig. 2), we wanted to see if we could go even further: why not try to build a full biological gate? Would it be possible to assemble a gate induced by a molecule other than gRNAs (Gander et al., 2016)? We decided to assemble an inducible biological NOT gate. This gate would consist of four basic parts (Fig. 3A): CYC1 promoter (BBa_K1723022), the repressor fused protein PCP-Mxi1, the scaffold scCYC1_PP7 (BBa_K1941003) and dCas9. The input will be galactose and the output will be GFP (Table 1).

Figure 3A. Design of the NOT gate, four basic parts:

- CYC1 promoter controls the GFP expression and is the target of scCYC1_PP7.

- PCP-Mxi1

- scCYC1_PP7 recruits PCP-Mxi1

- dCas9 drives the complex onto the CYC1 promoter

Figure 3B. Histogram and truth table both represent the two states of the system: when galactose is absent (input = 0), GPF is present (output = 1); when galactose is present (input = 1), GFP is absent (output = 0).. A bar graph shows fluorescence intensity of a strain transformed with CYC1-GFP, scCYC1_PP7, the repressor fused protein PCP-Mxi1 and GAL1-dCas9. GAL1 promoter is usually used as the regulatory element to drive GAL-inducible genes. Therefore, when all components are present in cells but galactose is absent, dCas9 is not expressed (input = 0). On the other hand, when galactose is present GAL1 is activated and dCas9 is expressed (input = 1).

Cells were grown overnight in 2% glucose (blue) or galactose (red) selective media and GFP levels were measured using FACS. The data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation for 3 independent experiments. A 78% repression of GFP expression was noticeable under galactose induction.

Figure 3C. Flow cytometry data (LSRII Snoopy) quantify the level of GFP expression under the control of CYC1 promoter. Cells in bright blue were overnight cultured in a 2% galactose selective medium while dark blue in 2% glucose selective medium. As expected, cells grown in galactose clearly show a decreased level of GFP expression: the two populations of cells show two different phenotypes, the median fluorescence values differ consistently between the ON and the OFF states indeed.

The NOT gate timing

Every system that takes an INPUT and returns an OUTPUT is characterized by a “time response”: an interval of time for which the response is transient i.e. it is not at steady state. In electrical engineering, the transient state of the system remains for a very short time while steady-state is the stage of the system as time t approaches infinity. We can extrapolate this definition to biological systems provided that we change timescale. Infinity would mean intuitively overnight or at steady state, but what would the transient state represent ? How long would this temporary state last ?

The FACS data (Fig. 4) gave us a first intuition about the evolution of the system: the OUTPUT of the NOT gate switches between the 1 and the 0 in overnight culture with 2% galactose; however, after just five hours of galactose induction the GFP signal coming from the cells is shifted.

Figure 4. scCyc1_PP7 recruits PCP-Mxi1 repressor protein: repression starts after 5 hours of galactose incubation. The repression of GFP expression under the control of CYC1 promoter was quantified by flow cytometry analysis (LSRII Snoopy) from overnight culture of yeast cells co-transfected with dCas9, PCP-Mxi1 repressor and scCYC1_PP7. The same strain of yeast was split in three different overnight cultures:

- In dark blue overnight culture with 2% glucose (selective medium).

- In red overnight culture with 2% glucose (selective medium); five hours before measurements, cells were washed and resuspended in 2% galactose SD minimal medium

- In bright blue overnight culture in 2% galactose SD minimal medium.

After five hours incubation in galactose (red), the scRNA system is switched on and cells start expressing dCas9 protein, which moves the repressor module on CYC1 promoter. The GFP expression curve shifts towards the overnight galactose population curve. Without glucose (dark blue), no repression was observed. The results obtained suggest that gene expression can be quantitatively regulated.

Activation vs repression: a powerful tool to make other gates

The inducible NOT gate was the one of the major milestone of our project. However, scientific curiosity always pushes matters to the limit. The next step would be to design other gates. For now we obviously did not have time to reach this goal, nevertheless we built the foundation for it: we assessed the efficiency of activation and repression in the same transfected cell. For a robust design of new gates, we would need a repression whenever both repressor and activator are present in the same cellular context. Indeed this is what we observed (Fig. 5).

The results obtained confirm our hypothesis that repression prevails over activation: when dCas9 expression is induced by galactose in a cell containing both activator and repressor modules, the GFP expression decreases. This is a crucial validation that our system can evolve in order to build complex gates, which need the property that repression gains when both activator and repressor modules coexist. This information is also fundamental for the implementation of the biological gates in CELLO.

Figure 5A. Design of the experiment activation vs repression on CYC1 promoter. scCYC1_MS2 (BBa_K1941005) targets region c3 of CYC1, while scTef1_PP7 targets region c6. The activation feature of the domain VP64 is nullified by the stronger repression induced by the chromatin condenser Mxi1.

Figure 5B. Histogram of relative normalized fluorescence of two different populations of same strain cells growing in overnight selective media. GFP levels were measured using FACS after overnight growth in 2% glucose or galactose selective media. Cells from CYC1-GFP strain were transfected with two additional plasmids: the first one carries GAL1-dCas9 and the two transcriptional modules PCP-Mxi1 and MCP-VP64. The second one contains the scaffolds RNA PP7 and MS2. Therefore, when GAL inducer is present, dCas9 acts as a Master Regulator: once expressed, both activator and repressor complexes become functional. Anyhow, data show that only the repressor module is responsible for the CYC1 regulation. This result is likely due to the chromatin remodeling feature of Mxi1.

Figure 5C. Flow cytometry data (LSRII Snoopy) quantify the level of GFP expression under the control of CYC1 promoter. Cells in bright blue were overnight cultured in a 2 % galactose selective medium while cells in dark blue in 2 % glucose selective medium.

Characterization of CYC1 promoter by scRNAs: plan for the future

Here we resume all the data collected about the regulatory elements of CYC1 promoter.

Figure 6. Expression control of CYC1 promoter in yeasts. A histogram shows fluorescence intensities of GFP when it is produced under basal level, activation or repression. With these basic elements, in principle all gates could be assembled.

Intelligene is a new way to design biological circuits. Expression of multiple RNA scaffolds simultaneously permits control of multiple genes in parallel, as in a ON/OFF regulatory switching program. In light of this, assembling together our activator and repressor modules, and exploiting the polymorphic nature of the CYC1 promoter, we can, in principle, build a wide variety of complex and robust circuits, based on a library of different guides RNA (DESKGEN)

Inducibility

Biological circuits need to be stimulated by specific inputs, especially when they are used in the context of a biosensor, in order to return an output and pass along the appropriate information. As such, inducibility is a key feature of Intelligene: by creating a NOT gate induced by galactose, we have a straightforward way to demonstrate a situation in which a specific output is dependent on a specific input. In this case, we chose an input which was appropriate for the system we were working in, since natural switches using galactose as an input already exist in yeast. These switches cause yeast to change their metabolism and genetic expression in the presence of galactose. In this experimental section, we aimed to phenotypically change the expression of two different reporter genes in a same population of cells. Moreover, we chose to work with the inducible promoter GAL1 and the constitutive promoter TDH3.

In our design, TDH3 is constitutively active and it produces red fluorescence protein (RFP). When galactose is introduced the expression pattern changes. This leads the GAL1 promoter to drive the expression of both GFP and a gRNA that inhibits TDH3 by CRISPRi. As a result of the galactose induction, cells change phenotype switching from RFP production to GFP production.

Unfortunately, due to time constraints, we did not managed to integrate all the plasmids carrying the parts needed to perform this experiment.

References:

- Zalatan JG, Lee ME, Almeida R, et al. Engineering Complex Synthetic Transcriptional Programs with CRISPR RNA Scaffolds. Cell. 2015;160(0):339-350. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.052.

- Gilbert LA, Larson MH, Morsut L, et al. CRISPR-Mediated Modular RNA-Guided Regulation of Transcription in Eukaryotes. Cell. 2013;154(2):442-451. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.044.

- Structural basis for the coevolution of a viral RNA–protein complex Jeffrey A Chao, Yury Patskovsky, Steven C Almo & Robert H Singer

- Robust digital logic circuits in eukaryotic cells with CRISPR/dCas9 NOR gates Miles W Gander, Justin D Vrana, William E. Voje, James M Carothers, Eric Klavins bioRxiv 041871; doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/041871