DEMONSTRATION

Hardware: Firing The Gene Gun

We wanted to check the validity of the gun’s design by testing if it could generate pressure pulses which would penetrate a plant cell wall. This was done using onion epidermal tissue, as the tissue layers are only one cell thick so would be the easiest to observe any penetration on microscope imaging.

For bombardment, we prepared the macrocarriers as described in the gun assembly protocol, steps 14-15. We then used simple agar TAP plates we had spare in the lab (approximately 1cm thick), and cut 2x1cm strips of brown onion epidermis to place on the plates.

We then pipetted 150mg of M10 tungsten microparticles, prepared according to our wetlab biolistics protocol, onto each macrocarrier. A fresh 16g CO2 cartridge lasted for around 20 bombardments, ranging from 130-155 psi (though the efficiency of this improved significantly once we became more experienced at pressurising the gun and wasted less CO2).

On inspecting the bombarded onion samples under the microscope, we found evidence of holes in the onion tissue. This suggests these pressures could be suitable for biolistics on plant cells, as the tungsten microparticles were capable of penetrating plant cell walls so should penetrate cells for biolistic transformation.

Our next step in developing the gene gun would be experiment with lower pressures, to find the most efficient pressure pulse for penetration of cells. In the future, we also aim to prove the gun’s use in carrying out chloroplast transformations, by attempting transformation of chlamydomonas samples.

Wetlab

Having developed the parts library for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and proved the concept of the biobricks standard syntax which allows for the regulated assembly into composite devices we investigating putting this under trial of real-life conditions to transform Chlamydomonas reinhardtii chloroplasts through biolistics. Please read more about the demonstration of the DIY biolistic gene gun we have developed in the lab this summer. Taking advantage of the aadA resistance gene which we were able to verify in E. coli colonies, we constructed this Phytobrick with a 5’ UTR psaA promoter and a rbcL 3’ UTR terminator, each flanked by the homology regions for insertion into the trnE2-psbH intergenic region (shown to yield high expression rates of the transgene).

As a side note, biolistics is a complex transformation process which requires a high precision in template preparation and sterility conditions. Our team, due to the time constraints of working with Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, were only able to shoot in our constructs once (takes approximately 2 weeks for the algae to grow and can be assayed on plate). To ensure we could obtain all the information from a single transformation we designed the experiment with the appropriate controls: negative control was biolistic transformation with water, positive control was transformation with verified backbones from Saul Purton algal biotechnology lab at UCL which contains the same homology regions are our constructs.

For each plasmid, the biolistics was done with 3 different concentrations of plates:

A,B -- 1 million cells per plate

C,D - 10 million cells per plate

E,F - 70 million cells per plate

The following constructs were shot in:

Construct 1

5’ end homology region + psaA 5’ UTR promoter + aadA gene (conferring resistance to spectinomycin) + rbcL 3’ UTR terminator + 3’ end homology region

Construct 2

5’ end homology region + psaA 5’ UTR promoter + aphA6 gene (conferring resistance to kanamycin) + rbcL 3’ UTR terminator + 3’ end homology region

Purton backbone plasmids were cloned with a aadA cassette into a unique Mlu1 site allowing for the insertion of a gene of interest at the cloning site (flanking enzymes Sph1 and Sap1). This plasmid could not be submitted to the registry due to lack of standard parts. The genes inserted were: VFP (verde fluorescent protein) and smGFP (green fluorescent protein), both codon-optimized for expression in the chloroplast.

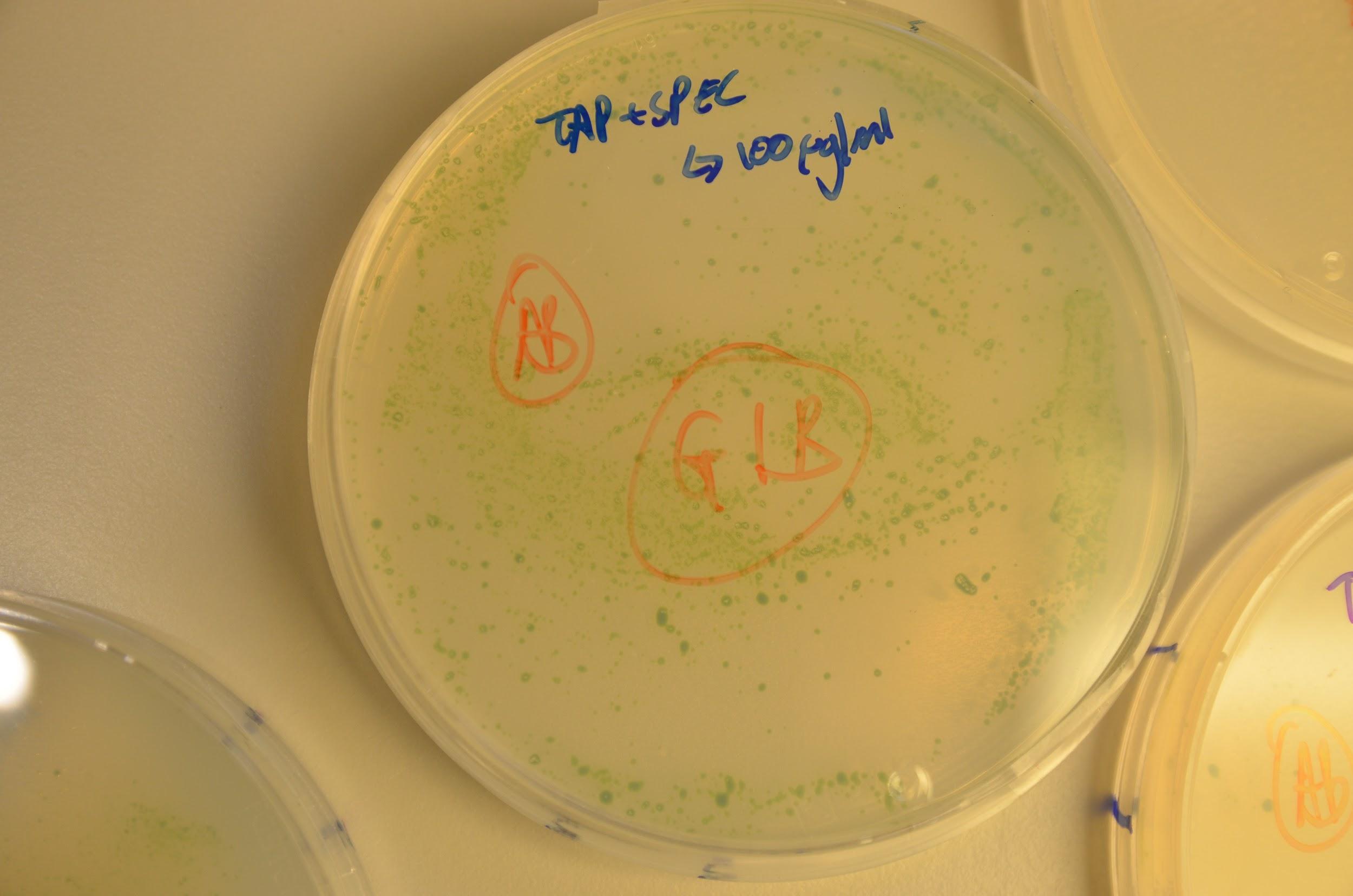

Below in the images we can see growth of the colonies on the kanamycin and spectinomycin plates.

Although this seems highly promising, some colonies were also seen to grow on the positive control plates. Our initial consideration was that a layer of algae had died and thus new colonies were forming on these and so avoiding contact with the antibiotic in the medium. This was disproved by replating colonies from each plate onto a new antibiotic+TAP media plate and growth was seen newly. If un-transformed we would have expected to see death of the re-streaked colonies. In addition to this, these antibiotic genes are not used in the department we are based in so we believe contamination is highly unlikely. Although this is only empirical evidence and molecular studies are needed to fully verify, we consider that the cause of growth on the negative control plates might have been due to lack of complete aseptic technique on our behalf.

A set of diagnostic colony PCR were conducted but were inconclusive. The first round was used by directly picking a colony and restreaking on a new plate. The primers were designed to anneal to the backbone and the inserted gene of interest, as this was indicative of both the presence of the backbone as well as the gene of interest. The gel showed a smear which we thought was due to an excess of genetic material. The PCR was repeated with the same conditions, but this time the picked colony was diluted into 10 μL of water before adding 1 μL to the PCR reaction mix. Further, a positive control for the backbones was included. Yet, still the results were inconclusive and needed more work trouble-shooting.

This first intent shows to a certain degree, the potential of parts to make modular constructs to transform chloroplasts in plant organisms, widening the scope of the iGEM competition for new and exciting ideas. Requiring optimization the protocol can be further improved by subsequent teams, as plant synthetic biology grows within iGEM. Future work also involves the use of the DIY open-source biolistics gene gun we have designed and built over the summer.

Cas9 Modelling

We managed to write a code that would enable anyone to predict the time taken to achieve homoplasmy using the appropriate model for Cas9 activity. This program is also designed to be flexible in the sense that various input parameters can be changed to fit the parameters of your experiment. For more information, please read a complete documentation of the program under the 'Modelling' page.