| Line 413: | Line 413: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

Given the facts above, we aimed to adjust MSCs to target the inflammatory tissue in different diseases by introducing various chemokine receptors and we constructed different plasmids of chemokine receptors:<br/> | Given the facts above, we aimed to adjust MSCs to target the inflammatory tissue in different diseases by introducing various chemokine receptors and we constructed different plasmids of chemokine receptors:<br/> | ||

| − | <table> | + | </p> |

| + | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

<td> | <td> | ||

| Line 455: | Line 456: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

In our ongoing experiments, we chose the model of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) , with CXCL12 changing most significantly whose corresponding receptor is CXCR4 and DTH(delayed type hypersensitivity), in which CXCL13 (with corresponding receptor of CXCR5) changes most significantly, to testify our design. We designed chemokine receptors to be expressed under the control of constructive promoter EF-1α therefore they could be consistently expressed by MSCs.<br/> | In our ongoing experiments, we chose the model of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) , with CXCL12 changing most significantly whose corresponding receptor is CXCR4 and DTH(delayed type hypersensitivity), in which CXCL13 (with corresponding receptor of CXCR5) changes most significantly, to testify our design. We designed chemokine receptors to be expressed under the control of constructive promoter EF-1α therefore they could be consistently expressed by MSCs.<br/> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 471: | Line 474: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| − | + | <p> | |

| + | <br/> | ||

<span class="note"> | <span class="note"> | ||

Figure 1.2.9 and Figure 1.2.10<br/> | Figure 1.2.9 and Figure 1.2.10<br/> | ||

| Line 492: | Line 496: | ||

<b><span class="glyphicon glyphicon-triangle-right"></span>Switch</b><br/> | <b><span class="glyphicon glyphicon-triangle-right"></span>Switch</b><br/> | ||

Engraftment success, survival, phenotype, and activity of MSCs strongly depend on the microenvironment presented at the site of delivery. This microenvironment often shares features of a healing wound, including inflammatory cells, neo-vasculature, and pro-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β. Tissue repair and tumor microenvironment may convert MSCs into contractile myofibroblasts (MFs) that form α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-containing stress fibers which leads to fibrogenesity and reduction of the clonogenicity and adipogenic potential.<br/> | Engraftment success, survival, phenotype, and activity of MSCs strongly depend on the microenvironment presented at the site of delivery. This microenvironment often shares features of a healing wound, including inflammatory cells, neo-vasculature, and pro-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β. Tissue repair and tumor microenvironment may convert MSCs into contractile myofibroblasts (MFs) that form α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-containing stress fibers which leads to fibrogenesity and reduction of the clonogenicity and adipogenic potential.<br/> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 507: | Line 512: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<span class="note"> | <span class="note"> | ||

| Line 589: | Line 595: | ||

Since it is unreasonable to apply eGFP/dTomato and luciferase to human bodies, we will improve our device and apply them to preclinical and clinical pharmaceutical research in the future. Making use of functional imaging, we will over express hFTH to be reported by MRI in vitro. The elevation of non-toxic intracellular ferritin iron storage causes a corresponding change in T2 relaxation time [4].<br/> | Since it is unreasonable to apply eGFP/dTomato and luciferase to human bodies, we will improve our device and apply them to preclinical and clinical pharmaceutical research in the future. Making use of functional imaging, we will over express hFTH to be reported by MRI in vitro. The elevation of non-toxic intracellular ferritin iron storage causes a corresponding change in T2 relaxation time [4].<br/> | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| + | </p> | ||

<table> | <table> | ||

<tr> | <tr> | ||

| Line 607: | Line 614: | ||

</tr> | </tr> | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | <p> | ||

<b><big>Transfection</big></b><br/> | <b><big>Transfection</big></b><br/> | ||

In our design, we chose lentivirus to transfer our system. However, given the oncogenicity risks of lentivirus, safer methods are necessary. In our future work, we try transfering our plasmids with various ways like electroporation, lipofectin, particle bombardment, etc.<br/> | In our design, we chose lentivirus to transfer our system. However, given the oncogenicity risks of lentivirus, safer methods are necessary. In our future work, we try transfering our plasmids with various ways like electroporation, lipofectin, particle bombardment, etc.<br/> | ||

Revision as of 16:50, 14 October 2016

Description

Background

Inflammation

Inflammation is a basic process in multiple diseases, such as IBD, trauma, arthritis, etc. and an indispensable part in the healing process of injured tissue, overlapping with proliferation and resolution. It’s a complex set of interactions among pathogens and immune systems in which chemokine and cytokine serve as a pivotal role in the communication.

Figure 1.1.1

Figure 1.1.1

This figure is from www.dermamedics.com.

In inflammatory condition, involved tissue produce a variety of cytokines and chemokines. These “inflammatory messengers” bind to specific receptors on target cells and stimulate the production of additional inflammatory signaling molecules, causing vasodilation while others cause migration of immune cells from the blood into the inflammatory area.

Traditional treatments

If the inflammatory phase is not successfully controlled and appropriately resolved, an excessive healing response characterized by scar formation can lead to tissue fibrosis [1]. What’s more serious is that excessive inflammatory reaction will cause overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory cytokines, evolving to fatal cytokine storm. The current treatments, however, including anti-inflammatory drugs and hormone, are unable to bring satisfactory results largely due to the difficulty in targeting the inflammatory lesions as well as side-effects including bone marrow suppression, metabolic disturbance and so on.

MSCs therapy

To our excitement, cell-based therapy, a potent and inspirational treatment, has progressively developed in recent years, especially MSCs (mesenchymal stem cells) therapy.

Figure 1.1.2

Figure 1.1.2

This figure is from Somoza R A, Correa D, Caplan A I. Roles for mesenchymal stem cells as medicinal signaling cells [J]. Nature Protocols, 2016, 11(1).

From an initial heterogeneous population, specific subpopulations can be obtained by either sorting with markers related to their roles in vivo or by priming them with stimulating solutions during expansion. MSCs have the in vitro ability to differentiate into mesodermal lineages and this differentiation is achieved by supplementing cultures with lineage-specific soluble factors and specific microenvironmental cues.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult multipotent progenitor cells derived from a variety of adult tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose, peripheral blood, dental pulp and fetal ones, like umbilical cord blood, Wharton's jelly, placenta and amniotic fluid. They are defined as cells which can differentiate into several lineages: osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes and should be adherent to plastic. Apart from the criteria above, MSCs are cells positive for CD34, CD73, CD90 and CD105 and negative for CD11b or CD14, CD19 or CD79 alpha, CD34, CD45 and HLA-DR.

As stem cells, they display immunomodulatory, anti-oxidative, vasculature-protective and anti-fibrotic properties [2] due to secretion of several paracrine factors and interaction with immunocytes. Given the beneficial characteristics, MSC treatment is regarded as a potent treatment for various kinds of diseases in which treating inflammatory diseases is one of the most researched and promising aspects of the clinical use of MSCs.

Figure 1.1.3

Figure 1.1.3

This figure is from Gazdic M, Volarevic V, Arsenijevic N, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Friend or Foe in Immune-Mediated Diseases.[J]. Stem Cell Reviews & Reports, 2015, 11(2):280-287.

MSCs may hamper T-cell-, B-cell-, antigen-presenting cell (APCs)- and natural killer (NK) cell–mediated immune responses. It is likely that MSCs educate immune cells to induce the generation of regulatory immune cells with tolerogenic properties. These regulatory immune cells, such as regulatory T-cells (Tregs), regulatory B-cells (Bregs), regulatory APCs and NK cells, will gather to create a tolerogenic environment suitable for modulating the immune response. For that, MSCs use multiple regulatory pathways with interleukin (IL-10) having a central role.

Limitations

Then how can MSCs be applied to patients?

In clinical settings, two administrating approaches of MSCs are in common use: direct local implantation versus intravascular administration. Since local implantation is limited for invasiveness, high risk of mortality and interruption of the local regulatory microenvironment, intravascular administration is now much more popular in clinical use [3].

However, intravascularly injected MSCs are still criticized for

Low homing efficiency,

Ambiguous distribution in human body,

which inevitably hinder their clinical application [4].

Now that upgrade is desperately in need, we, SYSU-MEDICINE, decide to engineer MSCs of next generation - MSCavalry.

MSCavalry - MSCs of Next Generation

Our goal is to engineer a set of MSCs (homo sapiens) acclimatizing to various inflammatory diseases. We suppose to endow MSCs with capability of traveling directionally and specifically to the inflammatory tissue or organ. At the same time, we are eager to figure out the distribution of intravascularly administrated MSCs. Thus, our design includes the following sections:

Chemokine receptor

MSCavalry are a series of MSCs optimized with all kinds of consistently expressed chemokine receptor (CXCR1, CXCR4, CXCR5, CCR2, CCR5, CCR7), which is able to bind specific chemokines elevated prominently in different kinds of inflammatory tissue or organ [5].

Marking proteins

MSCs are also equipped with genes under constructive promoter of several kinds of marking proteins: eGFP, dTomato and Luciferase, realizing accurate locating as well as highlighting.

Switch

Additionally, with a switch sensing fibrotic conversion, MSCs shifting to myofibroblast will consequently express gene of interest, which can be utilized as suicide switch in our future experiments[6].

Animal Models

To testify our design and lay a foundation for future clinical experiments, we will construct murine models of two prevalent inflammatory diseases: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH).

Detailed Design

To invest MSCs with higher homing efficiency and to quantify the MSCs in local inflammatory tissue, we constructed a frame consists of two basic parts responsible for sensing and positioning to inflammatory sites and marking MSCs both in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 1.2.1

Figure 1.2.1

Our first design includes the genes of chemokine receptors and a set of marking proteins under constructive promoter EF-1α.

Chemokine receptor

Chemokines are signal molecules controlling the migration and positioning of immune cells, which is critical for all immune cell movement ranging from the migration required for immune cell development and homeostasis, to that required for the generation of primary and amnestic cellular and humoral immune responses, to the pathologic recruitment of immune cells in disease [1].

Under the circumstance of inflammation, a complex process characterized by the coordinated movement of effector cells to the inflammatory sites as well as the exit of immune cells from peripheral sites to the draining lymphoid organs requires the induced expression of chemokines and their respective receptors on target cells.

Chemokine receptors are transmembrane proteins binding with chemokines and initiating cell migration.

Figure 1.2.2

Figure 1.2.2

Chemokine receptors are 7-transmembrane structure proteins coupling to G-protein. Following interaction with their specific chemokine ligands, chemokine receptors trigger a flux in intracellular calcium (Ca2+) ions, which causes cell responses, including chemotaxis that traffics the cell to a desired location.

There are approximately 20 signaling chemokine receptors responsible for the migration of diverse immune cells. Here is a table of chemokines and their corresponding chemokine receptors.

After comprehensive reading, we noticed that in different inflammatory sites or conditions (acute or chronic), dominant chemokines are also different and we summarized the dominant chemokines along with the corresponding chemokine receptors in various inflammatory diseases.

As for MSCs, they are able to migrate or dock preferentially to injured sites when infused in animal models of injury, and this property could be attributed to the expression of growth factor, chemokine receptors and extracellular matrix receptors on the surface of MSCs. Chemotaxis assays show that cultured MSCs migrate toward different growth factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which indicates that chemo-attraction directs systemically infused MSCs to inflammatory sites [7]. However, it is known that culture-expanded MSCs express chemokine receptors at low level that are responsible for the homing of leukocytes and hematopoietic stem cells which contribute to migration to inflammatory area. Previous studies have proved that MSCs stimulated by additional inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the culture medium express more chemokine receptors and show higher homing efficiency [8].

Given the facts above, we aimed to adjust MSCs to target the inflammatory tissue in different diseases by introducing various chemokine receptors and we constructed different plasmids of chemokine receptors:

Figure 1.2.3

Figure 1.2.3BBa_K1993002 |

Figure 1.2.4

Figure 1.2.4BBa_K1993001 |

Figure 1.2.5

Figure 1.2.5BBa_K1993004 |

Figure 1.2.6

Figure 1.2.6BBa_K1993012 |

Figure 1.2.7

Figure 1.2.7BBa_K1993003 |

Figure 1.2.8

Figure 1.2.8BBa_K1993013 |

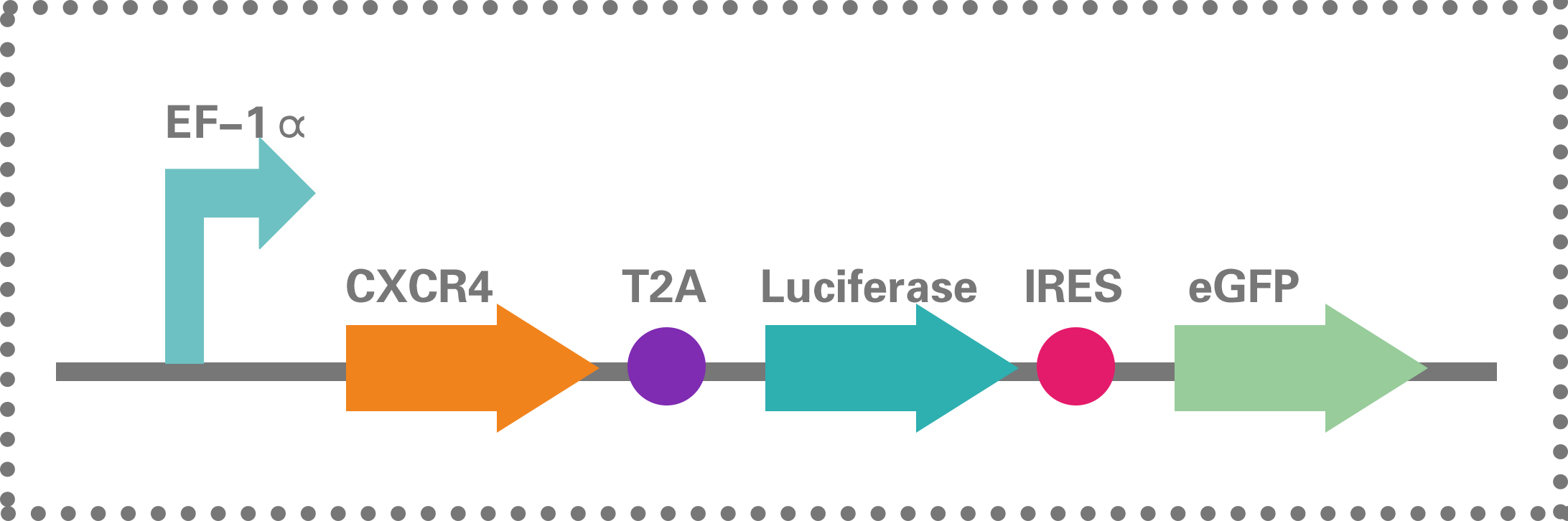

In our ongoing experiments, we chose the model of IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) , with CXCL12 changing most significantly whose corresponding receptor is CXCR4 and DTH(delayed type hypersensitivity), in which CXCL13 (with corresponding receptor of CXCR5) changes most significantly, to testify our design. We designed chemokine receptors to be expressed under the control of constructive promoter EF-1α therefore they could be consistently expressed by MSCs.

Figure 1.2.9

Figure 1.2.9 |

Figure 1.2.10

Figure 1.2.10 |

Figure 1.2.9 and Figure 1.2.10

In order to choose specific chemokine receptors for our two animal models, expressing level of various chemokines in DTH and IBD were measured respectively by qPCR. As is shown in the column graphs, CXCL12 ( with CXCR4 as corresponding chemokine receptor) is dominant in IBD while CXCL13 (the ligand of CXCR5) increases most significantly in DTH.

Marking system

For a proof of concept, we added proteins following chemokine receptor under the same promoter, eGFP/dTomato and firefly luciferase enzyme (Fluc) to illustrate the distribution of MSCs after injection both in vivo and in vitro.

In addition, comparing with a previous part, BBa_I712019, our new part, BBa_K1993005, improve the tracing function of luciferase and realize dual function of positioning for modified cells.

Figure 1.2.11

Figure 1.2.11

BBa_K1993005

For in vitro observation, we chose eGFP/dTomato, common used fluorescent proteins visible under fluorescence microscope.

As for in vivo monitor of the distribution of MSCs, we chose Luciferase which degrades luciferin therefore MSCs could be observed in live animals by IVIS Spectrum.

Switch

Engraftment success, survival, phenotype, and activity of MSCs strongly depend on the microenvironment presented at the site of delivery. This microenvironment often shares features of a healing wound, including inflammatory cells, neo-vasculature, and pro-fibrotic cytokines such as TGF-β. Tissue repair and tumor microenvironment may convert MSCs into contractile myofibroblasts (MFs) that form α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-containing stress fibers which leads to fibrogenesity and reduction of the clonogenicity and adipogenic potential.

Figure 1.2.12 |

Figure 1.2.13

Figure 1.2.13 |

Figure 1.2.12 and Figure 1.2.13

qPCR of α-SMA in MSCs. mRNA of α-SMA was detected of high concentration in inflammatory condition, whereas in normal condition mRNA of α-SMA were not detectable. Coherently in immunofluorescence, fluorescence could be observed in MSCs treated with TGF-β while not observable in control group.

With the promoter of SMA (pSMA) linking eGFP, we are able to detect the differentiated MSCs by observing conditionally expressed eGFP[1].

Figure 1.2.14

Figure 1.2.14

BBa_K1993014

Based on the results of our pre-experiments, we designed a switch under the promoter of α-SMA, which is able to detect inflammatory environment and to promote downstream genes.

In vitro proving

We decide to testify our system at three levels: whether engineered MSCs hold their phenotype, whether our system expresses as expected, and whether MSCs with chemokine receptors display higher ability of chemotaxis.

Phenotype

As mentioned above, MSCs are able to differentiate into three lineages: osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes, which is one of the most important standards for MSCs. Thus, we decide to testify whether engineered MSCs are able to be induced to differentiate into these three lineages and flow cytometry will be applied to evaluate the expressing level of specific surface molecules.

Expression of our system

As for check of expressing level of our system, qPCR will be applied for chemokine receptors while eGFP/dTomato will be observed under fluorescence microscope.

Chemotaxis assay

We will use transwell to identify the chemotaxis. When placed in the well of a multi-well tissue culture plate, plastic inserts create a two-chamber system. By placing cells in the upper chamber and chemokines on the lower one, chemotaxis is determined by counting the cells that have migrated through the filter pores from the underside of the filter.

In vivo proving

To testify our design and lay a foundation for the future clinical experiments, we will construct murine models of two prevalent inflammatory diseases: inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH).

IBD

Inflammatory bowel diseases including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are caused by the multiple factors such as genetic susceptibility, breakdown of mucosal immune tolerance, and self-immune activation to gut microbiota. Current treatment approaches are predominately aimed at suppressing overt inflammation and include the use of pharmacological agents, biologicals, and surgery to remove sections of inflamed bowel. However, these treatment modalities have limitations due to non-adherence and relapse. In the past decade, alternative cell-based immunosuppressive therapies utilizing immunosuppressive and differentiation properties of MSCs have been tested in clinical trials for both luminal and fistulizing forms of IBD[5]. In our project, MSCs engineered with the gene of CXCR4 and marking proteins will be used and evaluated.

Figure 1.2.15

Figure 1.2.15

BBa_K1993009

Grouping

IBD model with 42 BALB/c mice will be established and divided into 5 groups:

(1) 10 mice will be included in this experiment. After sensitization, 6 mice will be injected with MSCsCXCR4.

(2) 10 mice will be included in this experiment. After sensitization, 6 mice will be injected with MSCseGFP.

(3) 10 mice will be included in this experiment. After sensitization, 6 mice will be injected with saline.

(4) 6 mice will be treated with alcohol for the enema as the alcohol control.

(5) 6 mice without any further treatment will be as the normal control group.

The colon length, DAI score, survival rate, the concentration of the cytokines and HE staining will be recorded. In vivo MSCs with Luciferase will be observed by IVIS Spectrum.

DTH

DTH (delayed type hypersensitivity) is an experimental model for human allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), one of the prevalent skin diseases worldwide. At the peak of inflammation, effector T cells and various types of innate immune cells, particularly mast cells (MCs), are activated and produce a plethora of inflammatory cytokines that contribute to the eczematous lesions. Currently, topical application of corticosteroid is the first-line palliative measure for ACD with short-term outcome, while allergen identification to improve contact avoidance is still challenging[9]. Therefore, the unique immunomodulatory functions of MSCs on various types of immune cells may render them as a novel approach to desensitize allergic diseases. In our project, MSCs engineered with the gene of CXCR5 and marking proteins will be used and evaluated.

Figure 1.2.16

Figure 1.2.16

BBa_K1993008

Grouping

In our design, DTH model with 28 BALB/c mice will be established and divided into 4 groups:

(1) 8 mice will be included in this experiment. After sensitization, 6 mice will be injected with MSCsCXCR5.

(2) 8 mice will be included in this experiment with treatment of sensitization and injection of MSCseGFP to the caudal veins.

(3) 6 mice will be included in this experiment with treatment of sensitization and injection of PBS to the caudal veins.

(4) 6 mice containing in this group will receive identical volume of acetone/olive oil solution application to the backs and ears. PBS will be injected to the caudal veins.

Ear samples will be measured and harvested for qPCR, HE staining or immuno-fluorescence.

Major Achievements

1. Our modified MSCs still remained their own characteristics.

2. CCR7/CXCR4/CXCR5 were successfully overexpressed on our modified MSCs.

3. Chemotaxis of our engineered MSCs improved.

4. Marking proteins (eGFP/dTomato) worked.

5. Therapeutic effects of our engineered MSCs for IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) improved.

6. Therapeutic effects of our engineered MSCs for DTH (delayed type hypersensitivity) improved.

7. The switch element worked.

Future Work

Marking proteins

Since it is unreasonable to apply eGFP/dTomato and luciferase to human bodies, we will improve our device and apply them to preclinical and clinical pharmaceutical research in the future. Making use of functional imaging, we will over express hFTH to be reported by MRI in vitro. The elevation of non-toxic intracellular ferritin iron storage causes a corresponding change in T2 relaxation time [4].

Figure 1.3.1

Figure 1.3.1BBa_K1993006 |

Figure 1.3.2

Figure 1.3.2BBa_K1993011 |

Transfection

In our design, we chose lentivirus to transfer our system. However, given the oncogenicity risks of lentivirus, safer methods are necessary. In our future work, we try transfering our plasmids with various ways like electroporation, lipofectin, particle bombardment, etc.

Switch

In our future work, we will make use of switch to realize programmed death, marking differentiated MSCs and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression by introducing suicide gene, genes of marking proteins and IL-10.

Reference

1. Griffith J W, Sokol C L, Luster A D. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: positioning cells for host defense and immunity.[J]. Annual Review of Immunology, 2014, 32(1):659-702.

2. Karp J M, Leng T G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Homing: The Devil Is in the Details[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2009, 4(3):206-216.

3. Kalwitz G, Endres M, Neumann K, et al. Gene expression profile of adult human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by the chemokine CXCL7[J]. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 2009, 41(3):649-58.

4. Rossi M, Massai L, Diamanti D, et al. Multimodal molecular imaging system for pathway-specific reporter gene expression.[J]. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Official Journal of the European Federation for Pharmaceutical Sciences, 2016, 86:136-142.

5. Talele N, Fradette J, Davies J, et al. Expression of α-Smooth Muscle Actin Determines the Fate of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2015, 4(6):1016-1030.

6. Chinnadurai R, Ng S, Velu V, et al. Challenges in animal modelling of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for inflammatory bowel disease[J]. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2015(16):4779-4787.

7. B K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2012, 12(5):383-96.

8. Khaldoyanidi S. Directing Stem Cell Homing[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2008, 2(3):198-200.

9. Apparailly F, Tak P P, Ruffner M A, et al. Gene Therapy for Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases[M]. Birkhäuser, 2012.

iGEMxSYSU-MEDICINE

iGEMxSYSU-MEDICINE

IGEM SYSU-Medicine

IGEM SYSU-Medicine

SYSU_MEDICINE@163.com

SYSU_MEDICINE@163.com

SYSU-MEDICINE

SYSU-MEDICINE

iGEM SYSU-MEDICINE

iGEM SYSU-MEDICINE