Our Project

The hydrogen industry produces over 50 million metric tons of hydrogen per year, sourcing over 95% from fossil fuels [1].With the growing demand in refinery hydroprocessing, the global market for hydrogen is projected to reach over 700 billion metric tons by 2018 [1]. The overall aim of our project is to generate a clean, renewable source of hydrogen by expressing genes of the photosynthetic pathway within E. coli. Our first goal is to assemble the Chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway in E. coli in order to metabolically engineer chlorophyll in this organism. Up to date, no researcher has been successful in producing chlorophyll in non-photosynthetic organisms before [2]. Once produced, the chlorophyll will bind to Photosystem II, which is another pathway that we seek to construct within E. coli, to generate hydrogen ions, oxygen and electrons from the oxidation of water. The hydrogen ions and electrons generated from Photosystem II can then be converted to hydrogen gas using a Hydrogenase. Our modelling and human practice approaches will allow us to assess the viability of our hydrogen production on an industrial scale.

Motivation

In the last few decades, clean renewable energy has emerged as the frontrunner for research into alternatives to fossil fuels. Whilst running out of fossil fuels is not an immediate concern, as we continue to discover and produce fossil fuel reserves, the pollutions effects inherent, which cause climate change. At this rate, we will surpass an atmospheric [CO2] of 700 ppmv well before 2100. This would be an irreversible global catastrophe and severe climate volatility would ensue [3,4]. The Paris Agreement on climate change has come into effect on the 5th of October, 2016. This plan outlines certain emission targets that countries promise to conform to. Huge steps have been made towards developing a clean, reliable energy source with hydrogen being the primary candidate. Hydrogen combusts to produce water and energy without producing harmful emissions. To generate hydrogen within E. coli we are building on the work of previous Macquarie iGEM teams.

More than one-quarter of the world’s population live in remote areas that lack access to grid electricity. As a result of this they rely heavily on local diesel generating systems to meet their electricity demands. This reliance is paralleled with a variety of challenges including; time delays, higher prices, supply problems and increased vulnerability to outages.

Team Macquarie’s conceptual design, [The Living Battery] will provide individuals living in remote areas of Australia with a portable, renewable and low cost energy source. The H2 gas produced by “The Living Battery” can be used in fuel cells to power generators to meet the daily electricity demands of the community.

Currently, the high price of photovoltaic cells, and the low efficiency of solar to hydrogen systems are delaying the transition from fossil fuels to a clean energy source [5]. The H2 bio-chamber we are developing at Macquarie may hold the answers to this problem. Our hydrogen-producing, conceptual design could be used within rural communities; supplementing or even replacing traditional fossil fuels. An important part of this project is determining if our system will be embraced by our target market. A few of our team members ventured to outlying communities to talk to business owners and farmers. We discussed our technology and the concerns they had with adopting our technology. Based off their feedback we revised our [The Living Battery] prototype so that it incorporated kill switches for safety and a sealed culture tank with an import valve to reduce the risk of tank contamination.

Project Design

Chlorophyll plays an essential role in the photosynthetic pathway as it has the ability to absorb and transfer energy from light [6]. Chlorophyll molecules are embedded in thylakoid membranes within chloroplasts. Chlorophyll absorbs energy from incoming photons and uses resonance energy transfer to excite the p680 reaction centre of Photosystem II.

Chlorophyll a synthesis (Fig. 1) can be significantly increased in E. coli by eliminating the heme production pathway. We have achieved this by knocking out the hemH gene (encodes for Ferrochelatase), using CRISPR/Cas9 approach. Ferrochelatase utilises Protoporphyrin IX to make heme in the heme synthesis pathway (Fig. 2). Therefore, by making this enzyme dysfunctional, we can redirect all cellular Protoporphyrin IX to the Chlorophyll synthesis pathway [7]. We have designed and synthesised 12 gBlocks, which we hypothesise are necessary for chlorophyll biosynthesis. Using the 3A assembly method, we ligated these genes to form two large operons; operon 1 is 10.6 kbp and has been characterised as functional and operon 2 is 6.2 kbp but has not yet been characterised. We hope that the ligation of these two operons will allow us to characterise a unified chlorophyll biosynthesis part. Once chlorophyll a is synthesised within the E. coli, Photosystem II will have the energy required to oxidise water - producing hydrogen ions and electrons. Researchers are yet to successfully synthesise chlorophyll a in a non-photosynthetic organism. There may be unknown post-translational mechanisms that are essential for tetrapyrrole synthesis under variable environmental conditions [8].

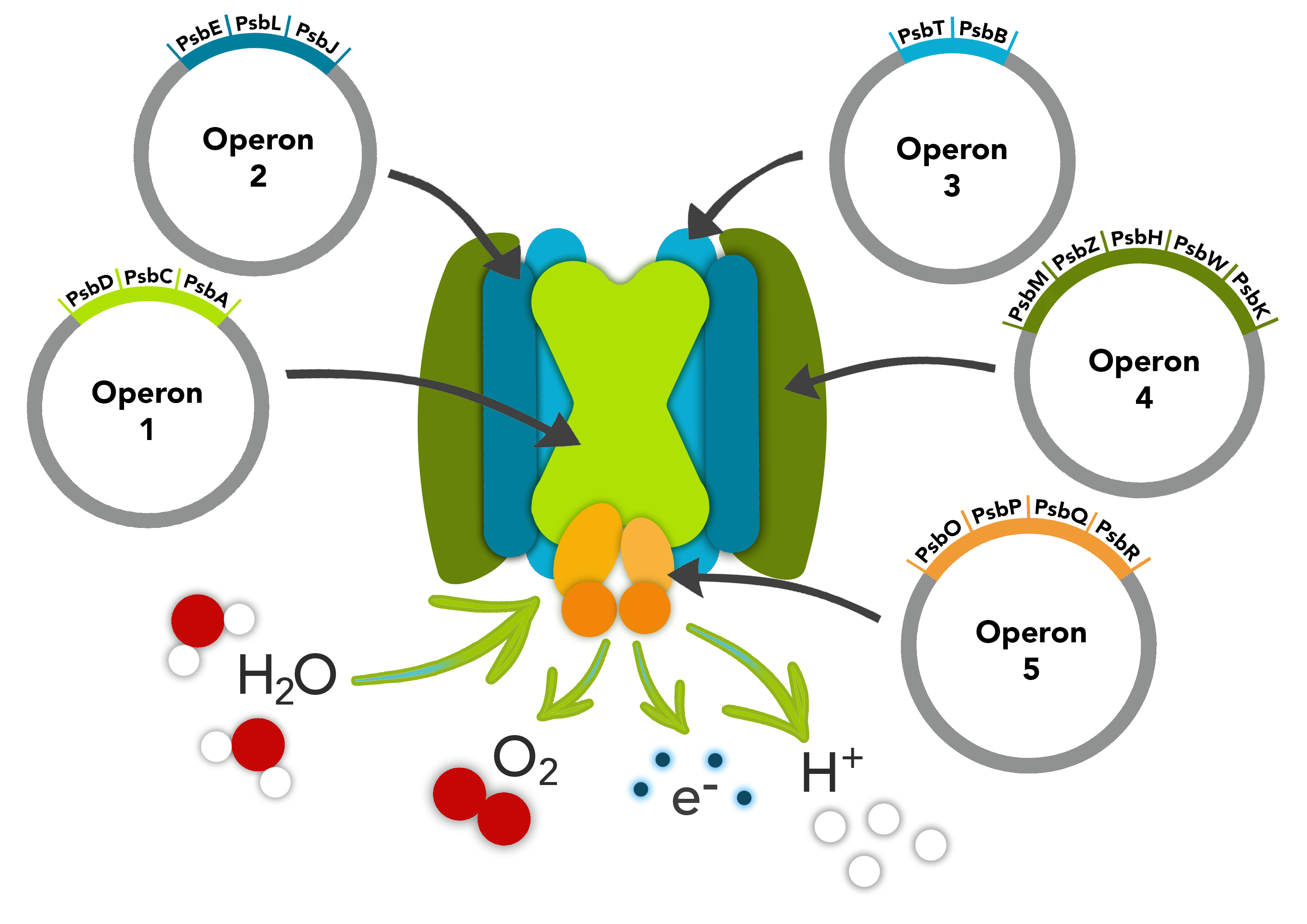

Photosystem II (Fig. 3) is one of the main protein complexes involved in the photosynthesis pathway. The complex is comprised of photons, chlorophyll-binding proteins that work with a pair of chlorophyll molecules (known as the P680 reaction centre), pheophytin molecules, plastaquinones, water, and oxygen. Photosystem II is a multimeric protein complex that binds a pair of chlorophyll molecules at its core, which work together to supply electrons to the electron transport system. This is done by splitting water molecules via absorbed photons in the Photosystem II reactions centre [9].

Developed from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the Photosystem II complex used has 17 genes. These 17 genes, involved with the Photosystem II construction, are grouped into 5 operons. In operon 1 there are 3 genes: psbD, psbC, and psbA. psbA encodes the major subunit D1, located in the reaction centre that forms a heterodimer with the D2 subunit encoded by psbD [10]. Attached to D1-D2 heterodimer is CP43, encoded by psbC, which is a subunit of the proximal antennae in Photosystem II [11].

Operon 2 consists of 3 genes psbE, psbL, and psbJ. psbE encodes for a cytochrome b559 subunit alpha [12]. psbL encodes the protein PsbL involved in the reaction centre and psbJ encodes for a core complex subunit [13]. Operon 3 consists of 2 genes psbT and psbB. psbT encodes for a small chloroplast hydrophobic polypeptide associated with the core complex [14], while psbB encodes for one of the subunits comprised in protein P680 of Photosystem II [15].

Operon 4 consists of 5 genes psbM, psbZ, psbH, psbW, and psbK. psbM and psbH encode for core complex subunit proteins [16] and psbZ, which is a stabilising protein for the Photosystem II/Light Harvesting Complex II [16]. psbW encodes for a transmembrane protein involved in Photosystem II dimer-stabilisation and photo-protection [17]. The final gene psbK encodes for a low molecular weight subunit of Photosystem II involved in stabilising the whole complex [18].

Operon 5 consists of 4 genes psbO, psbP, psbQ, and psbR. psbO encodes for a protein that acts to stabilise the cluster of four Mn2+ that forms the catalytic centre of the oxygen evolving complex (OEC) [19]. psbP, encodes a protein that optimizes the availability of Ca2+ and Cl- cofactors in the OEC in Photosystem II to maintain the active Manganese cluster [20]. psbQ, is involved with oxygen-evolving and the enhancer protein 3 [21]. psbR encodes for a protein essential for the stable assembly of psbP, that is a component of the OEC of photosystem II [22].

In 1939, Hans Gaffron discovered that unicellular green algae were able to produce hydrogen [23]. This was because of Hydrogenase activity under very low oxygen conditions [24]. Later he attempted to decouple the Hydrogenase activity from the oxidation of water by expressing Hydrogenase in a non-photosynthetic organism, but was unsuccessful [25]. Within this project we are attempting to produce [Fe] Hydrogenase, ferredoxin, and maturation enzymes. In conjunction they reduce hydrogen ions and electrons to produce hydrogen gas. As this is a new addition to our project we have synthesised all four genes (hyd1, hydEF, hydG, and Ferredoxin), as gBlocks and successfully ligated all 4 gBlocks into Biobricks. We are yet to confirm the expression of each gene in E. coli for characterisation, which if successful will allow hydrogen production (Fig. 4).

CRISPR/Cas9 was discovered as a component in the immune system of Streptococcus pyogenes. Since its discovery CRISPR/Cas9 has been an effective tool for genomic manipulation within many organisms [26]. The ability of CRISPR to manipulate E. coli genes has been demonstrated previously, with a near 100% editing success rate for insertions and deletions for double and single stranded DNA [27].

We have incorporated this technique into our project to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the Chlorophyll and Photosystem II pathways. By knocking out the hemH gene that produces Ferrachelatase in heme biosynthesis pathway [16] using CRISPR/Cas9 approach, more Protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) can be accumulated [7], providing more substrate for our Chlorophyll synthesis pathway. As a result, all cellular PPIX could be redirected for chlorophyll synthesis and can be used for the Photosystem II within E. coli.

We have also collaborated with the Singapore NTU iGEM team by testing the activity of their mammalian CRISPR/Cas9 in a bacterial system. Their Cas9 plasmids, including one wild type and two mutants, has been His-tag purified and coupled with our sgRNA in an vitro assay, in an attempt to characterise their parts.

References

- Sathre, R., et al., Life-cycle net energy assessment of large-scale hydrogen production via photoelectrochemical water splitting. Energy & Environmental Science, 2014. 7(10): p. 3264-3278.

- Brzezowski, P., et al., Mg chelatase in chlorophyll synthesis and retrograde signaling in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: CHLI2 cannot substitute for CHLI1. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2016.

- Goddéris, Y., et al., Rates of consumption of atmospheric CO 2 through the weathering of loess during the next 100 yr of climate change. Biogeosciences, 2013. 10(1): p. 135-148.

- Sanborn Scott, D., Fossil Sources: “Running Out” is Not the Problem. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2005. 30(1): p. 1-7.

- Hosseini, S.E. and M.A. Wahid, Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016. 57: p. 850-866.

- Eckhardt, U., B. Grimm, and S. Hörtensteiner, Recent advances in chlorophyll biosynthesis and breakdown in higher plants. Plant molecular biology, 2004. 56(1): p. 1-14.

- Jacobs, J.M. and N.J. Jacobs, Oxidation of protoporphyrinogen to protoporphyrin, a step in chlorophyll and haem biosynthesis. Purification and partial characterization of the enzyme from barley organelles. Biochemical journal, 1987. 244(1): p. 219-224.

- Czarnecki, O. and B. Grimm, Post-translational control of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2012.

- McEvoy, J.P. and G.W. Brudvig, Water-splitting chemistry of photosystem II. Chemical reviews, 2006. 106(11): p. 4455-4483.

- Marder, J.B., et al., Identification of psbA and psbD gene products, D1 and D2, as reaction centre proteins of photosystem 2. Plant Molecular Biology, 1987. 9(4): p. 325-333.

- Bricker, T.M. and L.K. Frankel, The structure and function of CP47 and CP43 in Photosystem II. Photosynthesis Research, 2002. 72(2): p. 131.

- Mor, T.S., et al., An unusual organization of the genes encoding cytochrome b559 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: psbE and psbF genes are separately transcribed from different regions of the plastid chromosome. Mol Gen Genet, 1995. 246(5): p. 600-4.

- Nowaczyk, M.M., et al., Deletion of psbJ leads to accumulation of Psb27–Psb28 photosystem II complexes in Thermosynechococcus elongatus . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics, 2012. 1817(8): p. 1339-1345.

- Ohnishi, N. and Y. Takahashi, PsbT polypeptide is required for efficient repair of photodamaged photosystem II reaction center. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2001. 276(36): p. 33798-33804.

- Cameron, K.M. and M. Carmen Molina, Photosystem II gene sequences of psbB and psbC clarify the phylogenetic position of Vanilla (Vanilloideae, Orchidaceae). Cladistics, 2006. 22(3): p. 239-248.

- Ferreira, K.N., et al., Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science, 2004. 303(5665): p. 1831-1838.

- Woolhead, C.A., et al., Conformation of a purified “spontaneously” inserting thylakoid membrane protein precursor in aqueous solvent and detergent micelles. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2001. 276(18): p. 14607-14613.

- Takahashi, Y., et al., Directed disruption of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast psbK gene destabilizes the photosystem II reaction center complex. Plant molecular biology, 1994. 24(5): p. 779-788.

- Murata, N. and M. Miyao, Extrinsic membrane proteins in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 1985. 10(3): p. 122-124.

- Roose, J.L., K.M. Wegener, and H.B. Pakrasi, The extrinsic proteins of photosystem II. Photosynthesis Research, 2007. 92(3): p. 369-387.

- Balsera, M., et al., The 1.49 Å resolution crystal structure of PsbQ from photosystem II of Spinacia oleracea reveals a PPII structure in the N-terminal region. Journal of molecular biology, 2005. 350(5): p. 1051-1060.

- Suorsa, M., et al., PsbR, a missing link in the assembly of the oxygen-evolving complex of plant photosystem II Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006. 281(1): p. 145-150.

- Gaffron, H., Carbon Dioxide Reduction with Molecular Hydrogen in Green Algae. American Journal of Botany, 1940. 27(5): p. 273-283.

- Lakatos, G., et al., Bacterial symbionts enhance photo-fermentative hydrogen evolution of Chlamydomonas algae. Green Chemistry, 2014. 16(11): p. 4716-4727.

- Stuart, T.S. and H. Gaffron, The mechanism of hydrogen photoproduction by several algae : I. The effect of inhibitors of photophosphorylation. Planta, 1972. 106(2): p. 91-100.

- Zhang, F., Y. Wen, and X. Guo, CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: progress, implications and challenges. Hum Mol Genet, 2014. 23(R1): p. R40-6.

- Li, Y., et al., Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli using CRISPR-Cas9 meditated genome editing. Metab Eng, 2015. 31: p. 13-21.

- Ferreira, G.C., et al., Structure and function of ferrochelatase. J Bioenerg Biomembr, 1995. 27(2): p. 221-9.