ChenXinIGEM (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

<html> | <html> | ||

| + | <style> | ||

| + | #Projects{ | ||

| + | color: inherit; | ||

| + | background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.1); | ||

| + | } | ||

| + | </style> | ||

<head> | <head> | ||

<meta charset="utf-8"> | <meta charset="utf-8"> | ||

| Line 47: | Line 53: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-7"> |

<br/><br/><br/><br/> | <br/><br/><br/><br/> | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| − | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/2/2c/T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg/1043px-T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.1 Division of work in bacteria consortium | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/2/2c/T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg/1043px-T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.1 Division of work in bacteria consortium"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/2/2c/T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg/1043px-T--Tianjin--experiment-1.jpg" width="100%"></a> |

| − | <figcation>Fig.1 Division of work in bacteria consortium | + | <figcation>Fig.1 Division of work in bacteria consortium</figcaption> |

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 66: | Line 72: | ||

<div class="space"></div> | <div class="space"></div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-5"> |

<!-- 这个是overview的位置,一共有四个方面 --> | <!-- 这个是overview的位置,一共有四个方面 --> | ||

<!-- 第一方面是改善培养基条件的 --> | <!-- 第一方面是改善培养基条件的 --> | ||

| Line 82: | Line 88: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-4"> |

<p style="font-size:18px"> | <p style="font-size:18px"> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

Whereas, if our bacteria consortium want to achieve their aim, they must work in harmony, therefore, it is necessary find a appropriate environment where these bacteria can normally or supernormally work together. <br/><br/></p> | Whereas, if our bacteria consortium want to achieve their aim, they must work in harmony, therefore, it is necessary find a appropriate environment where these bacteria can normally or supernormally work together. <br/><br/></p> | ||

<p style="font-size:18px" id="ModificationofP.p1">Primarily, we try several kinds of medium and decide to use W medium in the end; next, we optimize culture conditions by change carbon source, nitrogen source and some ions, then, we check growing situations and conditions of the degrading PET, TPA and EG; eventually, 1we can find out a suitable culture condition to co-culture our bacteria consortium. | <p style="font-size:18px" id="ModificationofP.p1">Primarily, we try several kinds of medium and decide to use W medium in the end; next, we optimize culture conditions by change carbon source, nitrogen source and some ions, then, we check growing situations and conditions of the degrading PET, TPA and EG; eventually, 1we can find out a suitable culture condition to co-culture our bacteria consortium. | ||

| Line 92: | Line 99: | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-8"> |

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| − | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/a/a4/T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg/1200px-T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.2 Idea about optimization of culture conditions | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/a/a4/T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg/1200px-T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.2 Idea about optimization of culture conditions"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/thumb/a/a4/T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg/1200px-T--Tianjin--experiment-2.jpg" width="100%"></a> |

| − | <figcation>Fig.2 Idea about optimization of culture conditions | + | <figcation>Fig.2 Idea about optimization of culture conditions</figcaption> |

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 172: | Line 179: | ||

</div></div> | </div></div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

<!-- copy start --> | <!-- copy start --> | ||

<!-- 这个图片是要进行修改的,用chemicaldraw,是红球菌降解的过程 改完了 --> | <!-- 这个图片是要进行修改的,用chemicaldraw,是红球菌降解的过程 改完了 --> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-2"></div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-8"> | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| Line 184: | Line 194: | ||

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-2"></div> | ||

<!-- copy end width可以设置成100%防止改变大小 --> | <!-- copy end width可以设置成100%防止改变大小 --> | ||

| Line 212: | Line 224: | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| − | + | <br/><br/><br/><br/> | |

<h3><b>2. Degradation of Ethylene Glycol | <h3><b>2. Degradation of Ethylene Glycol | ||

</b></h3> | </b></h3> | ||

| Line 225: | Line 237: | ||

<h3><b id="ProductionofPHA">3. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate</b></h3> | <h3><b id="ProductionofPHA">3. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate</b></h3> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size:18px"><i>Pseudomonas putida </i>is a natural producer of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates (mcl-PHA), a polymeric precursor of bioplastics. A genome-based in silico model for <i>P. putida KT2440</i> metabolism was employed to identify potential genetic targets to be engineered for the improvement of mcl-PHA production using glucose as sole carbon source. Here, overproduction of pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit AcoA in the <i>P. putida KT2440</i> wild type led to an increase of PHA production. In controlled bioreactor batch fermentations PHA production was increased by 33% in the acoA overexpressing wild type in comparison to <i>P. putida KT2440</i>. Transcriptome analyses of engineered PHA producing P. putida in comparison to its parental strains revealed the induction of genes encoding glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. In addition, NADPH seems to be quantitatively consumed for efficient PHA synthesis, since a direct relationship between low levels of NADPH and high concentrations of the biopolymer were observed. In contrast, intracellular levels of NADH were found increased in PHA producing organisms. Central metabolism of <i>P. putida KT2440</i> is shown right<sup>[4]</sup>.</p> | + | <p style="font-size:18px"><i>Pseudomonas putida </i>is a natural producer of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates (mcl-PHA), a polymeric precursor of bioplastics. A genome-based in silico model for <i>P. putida KT2440</i> metabolism was employed to identify potential genetic targets to be engineered for the improvement of mcl-PHA production using glucose as sole carbon source. Here, overproduction of pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit AcoA in the <i>P. putida KT2440</i> wild type led to an increase of PHA production. In controlled bioreactor batch fermentations PHA production was increased by 33% in the acoA overexpressing wild type in comparison to <i>P. putida KT2440</i>.</p> |

| + | <p style="font-size:18px" id="AdvantagesofB.s"> | ||

| + | Transcriptome analyses of engineered PHA producing P. putida in comparison to its parental strains revealed the induction of genes encoding glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. In addition, NADPH seems to be quantitatively consumed for efficient PHA synthesis, since a direct relationship between low levels of NADPH and high concentrations of the biopolymer were observed. In contrast, intracellular levels of NADH were found increased in PHA producing organisms. Central metabolism of <i>P. putida KT2440</i> is shown right<sup>[4]</sup>.</p> | ||

| Line 232: | Line 246: | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| − | + | <br/><br/><br/><br/> | |

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| Line 254: | Line 268: | ||

<div class="col-md-12"> | <div class="col-md-12"> | ||

| − | <h3><b | + | <h3><b >4. Advantages of <i>B. subtilis</i> strains |

</b></h3> | </b></h3> | ||

<p style="font-size:18px"id="EnhancedPromoter"><i>Bacillus subtilis</i> has an excellent secretion ability, displays fast growth, and is a nonpathogenic bacterium free of endotoxin <sup>[5] </sup>. It can, therefore, be used in food, enzyme, and pharmaceutical industries and can replace <i>Escherichia coli</i> for protein expression. Furthermore, the extracellular heterogeneous proteins secreted from <i>B. subtilis</i> are more convenient for recovery and purification in large-scale production during downstream processing <sup>[6] </sup>. </p> | <p style="font-size:18px"id="EnhancedPromoter"><i>Bacillus subtilis</i> has an excellent secretion ability, displays fast growth, and is a nonpathogenic bacterium free of endotoxin <sup>[5] </sup>. It can, therefore, be used in food, enzyme, and pharmaceutical industries and can replace <i>Escherichia coli</i> for protein expression. Furthermore, the extracellular heterogeneous proteins secreted from <i>B. subtilis</i> are more convenient for recovery and purification in large-scale production during downstream processing <sup>[6] </sup>. </p> | ||

| Line 324: | Line 338: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-5"> |

| − | <br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/> | + | <br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/><br/> |

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| Line 335: | Line 349: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="col-md-7"> |

<h3><b>8. Lipid Recovery From Biomass</b></h3> | <h3><b>8. Lipid Recovery From Biomass</b></h3> | ||

<p style="font-size:18px">The first goal of our research was to facilitate lipid recovery from biomass. The scientific community widespread disrupts the cyanobacterial cell envelope to achieve the goal. <sup>[10]</sup> (Seog JL et al. 1998)However, all these methods are not economical for large amounts of biomass or add additional cost and reduce the overall utility of the process. Our target is simply to make the cyanobacteria lyse at the appropriate time.</p> | <p style="font-size:18px">The first goal of our research was to facilitate lipid recovery from biomass. The scientific community widespread disrupts the cyanobacterial cell envelope to achieve the goal. <sup>[10]</sup> (Seog JL et al. 1998)However, all these methods are not economical for large amounts of biomass or add additional cost and reduce the overall utility of the process. Our target is simply to make the cyanobacteria lyse at the appropriate time.</p> | ||

| Line 367: | Line 381: | ||

| − | + | <div style="display: none"> | |

<!--这个地方是实验的地方,这个地方主要是实验的设计,有关张雨的表格是否修改,我们还是待定的--> | <!--这个地方是实验的地方,这个地方主要是实验的设计,有关张雨的表格是否修改,我们还是待定的--> | ||

<h2><b id="ExperimentDesign">Experiment Design</b></h2> | <h2><b id="ExperimentDesign">Experiment Design</b></h2> | ||

| Line 594: | Line 608: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-6"> | <div class="col-md-6"> | ||

| − | <p style="font-size:18px"id="OverexpressionofAcoAandAceA"><br/> | + | <p style="font-size:18px" id="OverexpressionofAcoAandAceA"><br/> |

We cultivate each of them and the mixture of three in in modified W0 culture medium which changed the carbon source from glucose to sugar for amplification. Then we still did the same 4*3(bacteria liquid and six primer sequences) orthogonal test. Luckily, three bacteria mixed well after cultivating for 12 hours. The number is collected in Table 3. | We cultivate each of them and the mixture of three in in modified W0 culture medium which changed the carbon source from glucose to sugar for amplification. Then we still did the same 4*3(bacteria liquid and six primer sequences) orthogonal test. Luckily, three bacteria mixed well after cultivating for 12 hours. The number is collected in Table 3. | ||

| Line 613: | Line 627: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| Line 699: | Line 713: | ||

<!--枯草芽孢杆菌的实验设计内容在这里面--> | <!--枯草芽孢杆菌的实验设计内容在这里面--> | ||

<h1 style="font-size:200%"><b id="ModificationofB.s">Modification of <i>Bacillus subtilis</i></b></h1> | <h1 style="font-size:200%"><b id="ModificationofB.s">Modification of <i>Bacillus subtilis</i></b></h1> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 715: | Line 728: | ||

<br/><br/> | <br/><br/> | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | </br></br></br></br> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

<a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/52/T--Tianjin--experiment-20.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.11 the construction of pHP13-P43 plasmid in advance"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/52/T--Tianjin--experiment-20.png" width="100%"></a> | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/52/T--Tianjin--experiment-20.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.11 the construction of pHP13-P43 plasmid in advance"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/5/52/T--Tianjin--experiment-20.png" width="100%"></a> | ||

| Line 721: | Line 735: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | <div class="row"> | + | |

| − | <div class="col-md- | + | <div class="row"> |

| + | <div class="col-md-1"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="col-md-10"> | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure id="BioactivityofPETaseandMHETase"> | <figure id="BioactivityofPETaseandMHETase"> | ||

| − | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/4/4d/T--Tianjin--kucao4.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.12 the construction of pHP13-P43 plasmid | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/4/4d/T--Tianjin--kucao4.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.12 the construction of pHP13-P43-PETase/MHETase plasmid"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/4/4d/T--Tianjin--kucao4.png" width="100%"></a> |

| − | <figcation>Fig.12 the construction of pHP13-P43 plasmid | + | <figcation>Fig.12 the construction of pHP13-P43-PETase/MHETase plasmid</figcaption> |

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 735: | Line 752: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="col-md-1"> | |

| − | </div> | + | </div> |

| + | </div> | ||

<!-- 图片做了一些改动的地方,改的是怎么构建质粒--> | <!-- 图片做了一些改动的地方,改的是怎么构建质粒--> | ||

| Line 755: | Line 773: | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

<figure> | <figure> | ||

| − | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/1a/T--Tianjin--kucaofig18.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.13 | + | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/1a/T--Tianjin--kucaofig18.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.13.cultivation of wild <i>B.subtilis</i> and two recombinant one in LB culture medium"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/1/1a/T--Tianjin--kucaofig18.png" width="100%"></a> |

| − | <figcation>Fig.13 | + | <figcation>Fig.13.cultivation of wild <i>B.subtilis</i> and two recombinant one in LB culture medium</figcaption> |

</figure> | </figure> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 772: | Line 790: | ||

<!--蓝藻组的实验设计--> | <!--蓝藻组的实验设计--> | ||

| − | <h1 style="font-size:200%"><b id="AControllableLipidProducer | + | <h1 style="font-size:200%"><b id="AControllableLipidProducer" >A Controllable Lipid Producer</b></h1> |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="col-md-12"> | <div class="col-md-12"> | ||

| − | <h3><b >1. Lysis genes(<i>13-19-15</i>)</b></h3> | + | <h3><b id="Lysisgenes">1. Lysis genes(<i>13-19-15</i>)</b></h3> |

| − | <p style="font-size:18px">P22 gp13,P22 gp19 and P22 gp 15 are holins, endolysins and auxiliary lysis factors respectively. To construct the holin-endolysin lysis system, they should be connected together with defined sequence. First of all, we obtained the three lysis genes which were synthesized by GENEWIZ separately. Then we use PCR to amplify this part. TA cloning and ligation of Blunt-ended DNA on the T vector were our original idea.However, <i>19</i> and <i>15</i> were spliced via TA cloning according to our presumption. <i>13</i> and <i>19-15</i> were ligated PCR overlap extension method of Warrens et al.<sup>[19]</sup>( Warrens AN et al. 1997)</p> | + | <p style="font-size:18px">P22 gp13,P22 gp19 and P22 gp 15 are holins, endolysins and auxiliary lysis factors respectively. To construct the holin-endolysin lysis system, they should be connected together with defined sequence. First of all, we obtained the three lysis genes which were synthesized by GENEWIZ separately. <br/></p> |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <p style="font-size:18px" id="ANickelSensingSignalSystem"> | ||

| + | Then we use PCR to amplify this part. TA cloning and ligation of Blunt-ended DNA on the T vector were our original idea.However, <i>19</i> and <i>15</i> were spliced via TA cloning according to our presumption. <i>13</i> and <i>19-15</i> were ligated PCR overlap extension method of Warrens et al.<sup>[19]</sup>( Warrens AN et al. 1997)</p> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 786: | Line 808: | ||

<div align="center"> | <div align="center"> | ||

| − | <figure | + | <figure > |

<a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8e/Igem-6803-e3.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.14 TA cloning and blunt end ligation"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8e/Igem-6803-e3.png" width="100%"></a> | <a href="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8e/Igem-6803-e3.png" data-lightbox="no" data-title="Fig.14 TA cloning and blunt end ligation"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2016/8/8e/Igem-6803-e3.png" width="100%"></a> | ||

<figcation>Fig.14 TA cloning and blunt end ligation</figcaption> | <figcation>Fig.14 TA cloning and blunt end ligation</figcaption> | ||

| Line 983: | Line 1,005: | ||

<li><a class="topLink" href="#DegradationofEG">Degradation of EG</a></li> | <li><a class="topLink" href="#DegradationofEG">Degradation of EG</a></li> | ||

<li><a class="topLink" href="#ProductionofPHA">Production of PHA </a></li> | <li><a class="topLink" href="#ProductionofPHA">Production of PHA </a></li> | ||

| + | <li><a class="topLink" href="#AdvantagesofB.s">Advantages of B.s </a></li> | ||

<li><a class="topLink" href="#EnhancedPromoter">Enhanced Promoter-p43 </a></li> | <li><a class="topLink" href="#EnhancedPromoter">Enhanced Promoter-p43 </a></li> | ||

<li><a class="topLink" href="#TheCooperationofTwo">The Cooperation of Two Promoters</a></li> | <li><a class="topLink" href="#TheCooperationofTwo">The Cooperation of Two Promoters</a></li> | ||

| Line 990: | Line 1,013: | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<li><a href="#">Experiment Design </a> | <li><a href="#">Experiment Design </a> | ||

| Line 1,002: | Line 1,027: | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<li><a href="#">Optimization of Culture Conditions two </a> | <li><a href="#">Optimization of Culture Conditions two </a> | ||

Latest revision as of 14:55, 28 November 2016

Bacteria Consortium

Overview

After Yoshida and his co-workers found and isolated Ideonella sakaiensis 201-F6, which produced two enzymes to degrades PET, we kept very high interests at their works and also came up with many ordinary ideas to increase the efficiency of degradation reaction. Bacteria consortium is one of the most creative ideas.

The inspiration of this idea comes from nature and also learns from nature. Actually, bacteria never exist alone in our nature, they co-work and cooperate together to achieve an aim or live better in a special condition. Thinking from this point, we established a special bacteria consortium for this enzyme catalysis reaction.

1. Optimization of Culture Conditions

In order to improve efficiency of degrading PET, we are determined to co-culture Pseudomonas putida KT2440, Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 and Bacillus stubtilis 168 (or Bacillus stubtilis DB 104). In our bacteria consortium, work of degradation is divided several parts as follows:

1.Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 is responsible for degrading TPA (terephthalic acid) to remove substrate inhibition;

2. Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is responsible for degrading EG (ethylene glycol) to remove substrate inhibition, and contribute to produce degradable plastics PHA (polyhydroxyalkanoate).

3. Bacillus stubtilis 168 (or Bacillus stubtilis DB 104) is responsible for secreting PETase and MHETase as the main player of degrading PET.

Whereas, if our bacteria consortium want to achieve their aim, they must work in harmony, therefore, it is necessary find a appropriate environment where these bacteria can normally or supernormally work together.

Primarily, we try several kinds of medium and decide to use W medium in the end; next, we optimize culture conditions by change carbon source, nitrogen source and some ions, then, we check growing situations and conditions of the degrading PET, TPA and EG; eventually, 1we can find out a suitable culture condition to co-culture our bacteria consortium.

2. Modification of Pseudomonas putida KT2440

P.putida KT2440 is one of bacteria which can utilize ethylene glycol (EG) at a high speed and meanwhile produces mcl-PHA. In 1988, Lageveen and his co-workers first found mcl-PHA in P.putida KT2440. And then, the metabolism of producing PHA in P.putida KT2440 was reasearched, which found the gene AcoA was the key gene in the procedure. José Manuel Borrero-de Acuña and his co-workers improved the yield by 33% by overexpressing AcoA.

From Björn Mückschel’s works, Ethylene Glycol Metabolism by Pseudomonas putida was found. The key enzymes were identified by comparative proteomics. In P. putida JM37, tartronate semialdehyde synthase (Gcl), malate synthase (GlcB), and isocitrate lyase (AceA) were found to be induced in the presence of ethylene glycol or glyoxylic acid. Under the same conditions, strain KT2440 showed induction of AceA only.

From those studies, we decided to overexpress AcoA and AceA in P.putida KT2440 to help utilize EG as energy source for its growth.

3. Modification of Bacillus subtilis

After some attempt in E.coli and yeast, we look for a new type of host cells- B.subtilis for more secretion. In our experiment, the genes encoding two enzymes are for the first time expressed in S.cerevisiae. Increased yields of PETase and MHETase enzymes are achieved when B. subtilis strains 168 and DB104 (deficient in two and three extracellular proteases, respectively[1]) were transformed with the recombinant plasmid with the help of the enhanced promoter-p43.

4. A Controllable Lipid Producer

Cyanobacteria are excellent organisms for biofuel production. We thus have selected Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 as the source of carbon in our mixed bacteria system. Our target is simply to make the cyanobacteria lyse at the appropriate time by transforming a plasmid contained three bacteriophage-derived lysis genes which were placed downstream of a nickel-inducible signal transduction system into the Synechocystis 6803.

In this part of our project, Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 was selected as a model organism as the source of carbon in our mixed bacteria system. We simply to establish a cell wall disruption process which could make the cyanobacteria lyse at the appropriate time.

Theoretical Background

1. Degradation of Terephthalate

Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1 is thought to be capable of degrading a wide range of aromatic compounds including terephthalate acid (TPA). in 2006, a reliable pathway consisting of Distinct ring cleavage dioxygenase systems and protocatechuate (PCA) pathway was come up with, and the proposed degradation pathway for TPA is shown as below[2].

2. Degradation of Ethylene Glycol

By employing growth and bioconversion experiments, directed mutagenesis, and proteome analysis, it is found that Pseudomonas putida KT2440 does not grow within 2 days of incubation, compared to Pseudomonas putida JM37 which can grow rapidly under the same conditions. The key enzymes and specific differences between the two strains were identified by comparative proteomics. In P. putida JM37, tartronate semialdehyde synthase (Gcl), malate synthase (GlcB), and isocitrate lyase (AceA) were found to be induced in the presence of ethylene glycol or glyoxylic acid. Under the same conditions, strain KT2440 showed induction of AceA only. Postulated pathway for the metabolism of ethylene glycol in Pseudomonas putida strains KT2440 and JM37 is shown left[3].

3. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate

Pseudomonas putida is a natural producer of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoates (mcl-PHA), a polymeric precursor of bioplastics. A genome-based in silico model for P. putida KT2440 metabolism was employed to identify potential genetic targets to be engineered for the improvement of mcl-PHA production using glucose as sole carbon source. Here, overproduction of pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit AcoA in the P. putida KT2440 wild type led to an increase of PHA production. In controlled bioreactor batch fermentations PHA production was increased by 33% in the acoA overexpressing wild type in comparison to P. putida KT2440.

Transcriptome analyses of engineered PHA producing P. putida in comparison to its parental strains revealed the induction of genes encoding glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. In addition, NADPH seems to be quantitatively consumed for efficient PHA synthesis, since a direct relationship between low levels of NADPH and high concentrations of the biopolymer were observed. In contrast, intracellular levels of NADH were found increased in PHA producing organisms. Central metabolism of P. putida KT2440 is shown right[4].

4. Advantages of B. subtilis strains

Bacillus subtilis has an excellent secretion ability, displays fast growth, and is a nonpathogenic bacterium free of endotoxin [5] . It can, therefore, be used in food, enzyme, and pharmaceutical industries and can replace Escherichia coli for protein expression. Furthermore, the extracellular heterogeneous proteins secreted from B. subtilis are more convenient for recovery and purification in large-scale production during downstream processing [6] .

5. Enhanced Promoter-p43

In order to increase secretion, some enhanced promoters are necessary. However, native gene in a high-copy number plasmid was found to be unstable in B. subtilis[5] . To optimize the production and the stability of the expression vectors, both the promoter and the signal sequence of PETase were replaced by B. subtilis P43 promoter, a constitutively expressed promoter. This overcame the plasmid instability problem.

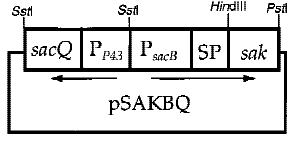

6. The Cooperation of Two Promoters-p43+psacB

Interestingly, the cooperation of two promoters in B. subtilis are easily found. For example, An endoglucanase from Bacillus akibai I-1 was successfully overexpressed in Bacillus subtilis 168 by the help of p43 promoter and the expression level of the recombinant enzyme was greatly enhanced by using the sucrose-inducible psacB promoter[7] .The construction of plasmid is in the Figure 1 . Thus, we are willing to try whether the combination of p43 and psacB can make a difference in the secretion of enzyme.

7. Lipid Producer

Photosynthetic microorganisms, including eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria, are being optimized to overproduce numerous biofuel. According to previous data, algae accumulate large quantities of lipid as storage materials, but they do this when under stress and growing slowly. By contrast, cyanobacteria accumulate lipids in thylakoid membranes, which are associated with high levels of photosynthesis and a rapid growth rate. Thus, photo-synthetic bacteria have a natural advantage for producing lipids at a high rate. Furthermore, being prokaryotes can be improved by genetic manipulations much more readily than can eukaryotic algae. [8] Therefore, we decided to do something to make cyanobacteria ,the lipid producer, more appropriate for our project.

Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 has larger capacity of lipid production than Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 but accumulates most of the product in the cell because of the imbalance of the rates of lipid production and secretion. Initially, we intended to do something to increase lipid secretion by knocking the wzt gene[9] (Akihiro Kato et al. 2016), however, Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 wasn’t able to revive in two-week shaking cultivation. So we turned into Synechocystis sp.PCC 6803.

8. Lipid Recovery From Biomass

The first goal of our research was to facilitate lipid recovery from biomass. The scientific community widespread disrupts the cyanobacterial cell envelope to achieve the goal. [10] (Seog JL et al. 1998)However, all these methods are not economical for large amounts of biomass or add additional cost and reduce the overall utility of the process. Our target is simply to make the cyanobacteria lyse at the appropriate time.

We found that the cyanobacterial cell envelope is composed of 4 layers: the external surface layers ;the outer membrane; the polypeptidoglycan which is considerably thick, and the cytoplasmic membrane. [11] ( Hoiczyk E et al. 2000)To break up the peptidoglycan layer, we applied the holin-endolysin lysis strategy used by bacteriophages to exit bacterial cells[12] (Wang IN et al. 2000).Endolysins are peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes that attack the covalent linkages of the peptidoglycans that maintain the integrity of the cell wall. In addition to endolysins, some auxiliary lysis factors are involved in cleaving the oligopeptide linkages between the peptidoglycan and the outer membrane lipoprotein. Holins are small membrane proteins that produce nonspecific lesions (holes) in the cytoplasmic membrane from within, allow the endolysins and auxiliary lysis factors to gain access to the polypeptidoglycan layers, and trigger the lysis process. In this way, the cell wall is easy to break up.

9. Control The Lysis System

To control the appropriate time, a nickel sensing/responding signal system[13] (Garcia-Dominguez M et al. 2000) was used to control the timing of the expression of phage lysis genes in Synechocystis 6803.

Our strategy for achieving our target is to construct a expression vector pCPC3031-Ni-13-19-15 introduced the Salmonella phage P22 lysis cassette (13-19-15) with a Spectinomycin selection marker downstream of the promoter Pni, a nickel responding signal operon. Synechocystis 6803 with the pCPC3031-Ni-13-19-15 will lyse after Ni2+ addition.

Modification of Pseudomonas putida KT2440

1. Overexpression of AcoA and AceA in P.putida KT2440

AcoA and AceA are the crucial genes for production of PHA and utilization of EG, so overexpressing these two genes is beneficial to improve the efficiency of degradation reaction and accumulation of PHA. Based on this idea, we established a expression vector which can be used in P.putida KT2440.

Based on the shuttle plasmid pBBR1MCS-2, we established the overexpression vector. The target genes were obtained by colony PCR and were ligated to the plasmid by T4 DNA ligase. The target genes are leaded by a T3 promoter.

After we established the vector, we transformed it to competent cell of E.coli and amplified it.

2. Electroporation of P.putida KT2440

Procedure:

(1) 10 ml LB + 0.1 ml Overnight culture of P.putida KT2440;

(2) Centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 degrees centigrade;

(3) Wash the precipitation (P.putida KT2440) with ice cold Elec-Buffer * 3;

(4) Re-suspend in 20 microliter Elec-Buffer;

(5) 4 microliter or 9 microliter suspension + 1 microliter of DNA(50 ng);

(6) Place 5 microliter or 10 microliter samples in Electrode Pin(5.6 mm diameter?) (50 microliter in Electrode Pin(1 mm diameter)?);

(7) Electroporation at 1.2 kV, 200 Ω, and 25 μF.

(8) Add 1-2 ml SOC Medium and culture at 30 degrees centigrade for 2 h

(9) Spread on selection plate (LB agar with Kanamycin)

P.S. Elec-Buffer is 10% Glycerol.

3. Detection of PHA in P.putida KT2440

Procedure:

(1) take a certain amount of bacteria in the extraction bottle, add 15mL chloroform for each 1g bacteria, and place the extraction bottle in a high-pressure reaction kettle at 100 degrees Centigrade to react for 4h.

(2) After cooling, filter.

(3) Slowly add 10 times the volume of ethanol, cooling and stirring.

(4) Place at 4 degrees centigrade over night.

(5) After pressure reduction and pressure filtration, dehydrate the PHA in vacuum drying oven for 24h, weigh and record.

Modification of Bacillus subtilis

1. Recombinant Plasmid Construction and Transformation

E.coli with gene of PETase and MHETase and vector of pHP13-p43 has been inoculated in tubes of LB culture. The plasmid is constructed in advance(Figure 13).

The Plasmids were isolated and enzyme digested using EcoR I and BamH I restriction enzyme. After gel extraction to get right band, construction of pHP13-p43 + PETase and pHP13-p43 + MHETase were caught out. The successfully constructed vectors, pHP13-p43 + PETase and pHP13-p43 + MHETase, were respectively transferred into E.coli and then E.coli were cultivated on chloramphenicol-containing LB plates to filter positive colony.(Figure 14) The positive colony of PETase and of MHETase were inoculated into tubes containing LB with chloramphenicol. Then well-constructed vectors were isolated. Vectors were respectively transferred into B.subtilis and then B.subtilis were cultivated on erythromycin-containing LB plates to filter positive colony. Above all, we got 2 strains of B.subtilis respectively secret PETase and MHETase.

2. Bioactivity of PETase and MHETase

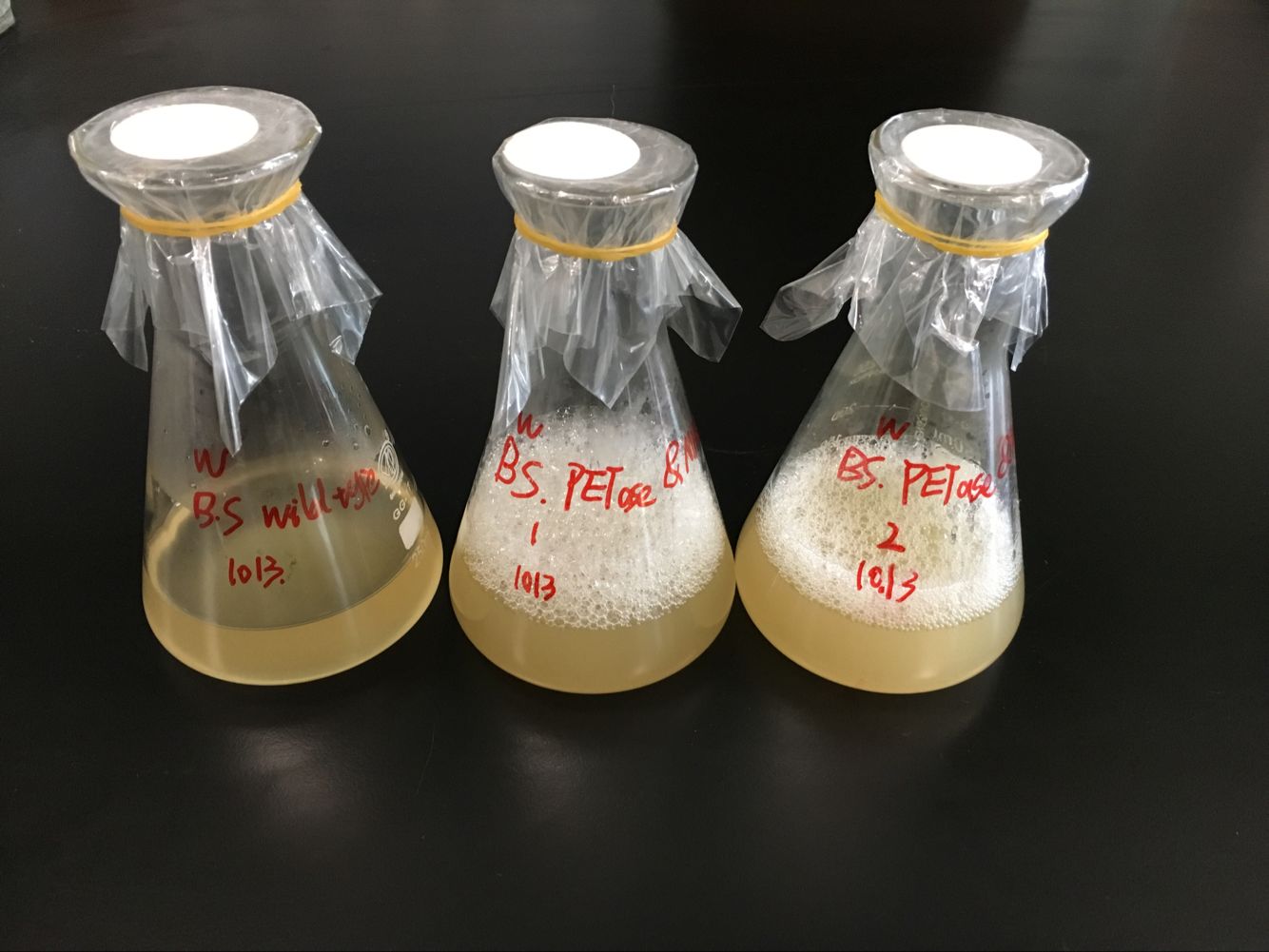

In order to test the bioactivity of PETase and MHETase, we have two methods. First, we use hydrolysis of pNPA through degradation rate. We cultivated wild B.subtilis and recombinant one in modified LB culture medium, which add PNPA solution through filtering(pNPA has a very low solubility in water).

After some days, we take 1 ml bacteria liquid each and centrifuge them for 12000r/min. Then we take the supernatant and measure solution absorbance at 400 nm, which is an obvious absorption peak of p-nitrophenol. If there is an an obvious absorption peak at 400 nm, we prove the bioactivity of PETase and MHETase in B.subtilis.

Second, we make orthogonal test. We cultivated wild B.subtilis and two recombinant one in LB culture medium(Figure 15). We put PET in wild one and one of the recombinant B.subtilis. Then, we imitate of the first methods and measure solution absorbance at 260 and 240 nm , which is an obvious absorption peak of MHET and TPA.

A Controllable Lipid Producer

1. Lysis genes(13-19-15)

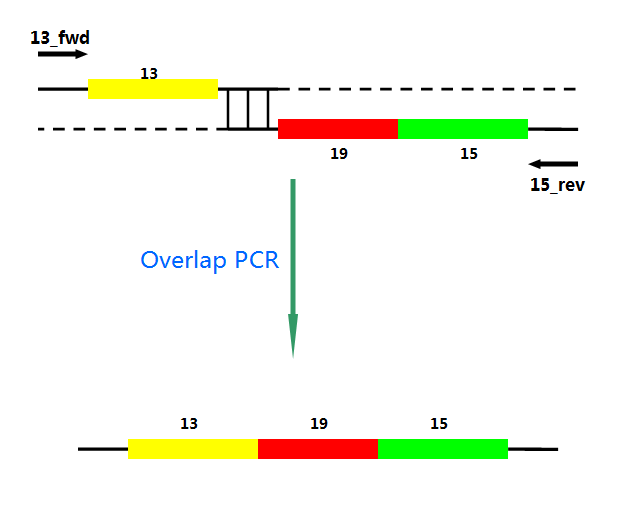

P22 gp13,P22 gp19 and P22 gp 15 are holins, endolysins and auxiliary lysis factors respectively. To construct the holin-endolysin lysis system, they should be connected together with defined sequence. First of all, we obtained the three lysis genes which were synthesized by GENEWIZ separately.

Then we use PCR to amplify this part. TA cloning and ligation of Blunt-ended DNA on the T vector were our original idea.However, 19 and 15 were spliced via TA cloning according to our presumption. 13 and 19-15 were ligated PCR overlap extension method of Warrens et al.[19]( Warrens AN et al. 1997)

2.A Nickel Sensing/Responding Signal System(pCPC3031-Ni)

Ni activates the transcription of downstream genes of Pni and positively autoregulates its own synthesis. The amount of mRNA increased about 20-fold within 4 h after Ni addition. First, Pni was cloned into pCPC3031 and was amplified by using PCR. Then we cut the plasmid with Nru I, after that the lysis genes, 13-19-15, were placed downstream of Pni. What’ more, we handed in the plasimids for sequencing, which confirmed its correctness.

References

[1] He Wang, Ruijin Yang3,Xiao Hua, Wei Zhao, Wenbin Zhang. Functional Display of Active β-Galactosidase on Bacillus subtilis Spores Using Crust Proteins as Carriers

[2]Hirofumi Hara, Lindsay D. Eltis, Julian E. Davies, and William W. Mohn (2007): Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals a Bifurcated Terephthalate Degradation Pathway in Rhodococcus sp. Strain RHA1. In JOURNAL OF BACTERIOLOGY, Mar. 2007, p. 1641–1647. doi:10.1128/JB.01322-06

[3]Bjorn Mückschel,a Oliver Simon,b Janosch Klebensberger,a Nadja Graf,c Bettina Rosche,d Josef Altenbuchner,c Jens Pfannstiel,b Armin Huber,b and Bernhard Hauera (2012): Ethylene Glycol Metabolism by Pseudomonas putida. In Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78 (24), pp. 8531–8539.

[4]José Manuel Borrero-de Acuña, Agata Bielecka, Susanne Häussler, Max Schobert, Martina Jahn, Christoph Wittmann, Dieter Jahn1 and Ignacio Poblete-Castro (2014): Production of medium chain length polyhydroxyalkanoate in metabolic flux optimized Pseudomonas putida. In Microbial Cell Factories 13 (88).

[5] Sen-Lin Liu, Kun Du. Enhanced expression of an endoglucanase in Bacillus subtilis by using the sucrose-inducible sacB promoter and improved properties of the recombinant enzyme

[6] Ruiqiong Ye, June-Hyung Kim, Byung-Gee Kim, Steven Szarka, Elaine Sihota, Sui-Lam Wong High-Level Secretory Production of Intact, Biologically Active Staphylokinase from Bacillus subtilis

[7] Zhongjun Chen,Cai Heng ,Zhengying Li ,Xinle Liang , Shangguan Xinchen Expression and secretion of a single-chain sweet protein monellin in Bacillus subtilis by sacB promoter and signal peptide

[8]Espaux L, Mendez-Perez D, Li R, Keasling JD (2015) Synthetic biology for microbial production of lipid-based biofuels. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 29:58-65

[9]Akihiro Kato, Kazuhide Use, Nobuyuki Takatani, Kazutaka Ikeda, Miyuki Matsuura, Kouji Kojima (2016) Modulation of the balance of fatty acid production and secretion is crucial for enhancement of growth and productivity of the engineered mutant of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongates. Biotechnol Biofuels9:91-101.

[10]Seog JL, Byung-Dae Y, O. H-M (1998) Rapid method for the determination of lipid fromthe green alga Botryococcus braunii. Biotechnol Tech 12:553–556.

[11]Hoiczyk E, HanselA(2000) Cyanobacterial cell walls: News from an unusual prokaryotic envelope. J Bacteriol 182:1191–1199.

[12]Wang IN, Smith DL, Young R (2000) Holins: The protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu Rev Microbiol 54:799–825.

[13]Garcia-Dominguez M, Lopez-Maury L, Florencio FJ, Reyes JC (2000) A gene clusterinvolved in metal homeostasis in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 182:1507–1514.

[14] Kang Zhou, Kangjian Qiao, Steven Edgar & Gregory Stephanopoulos.Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. doi:10.1038/nbt.3095

[15] Junjie Yang,Bingbing Sun,He Huang,Biao Chen,Chongmao Xu,Xin Wang,Jinle Liu ,Liuyang Diao .Multiple-site genetic modifications in Escherichia coli using lambda-Red recombination and I-SceI cleavage. doi:10.1007/s10529-015-1878-1

[16] T. B. Causey, S. Zhou, K. T. Shanmugam, and L. O. Ingram.Engineering the metabolism of Escherichia coli W3110 for the conversion of sugar to redox-neutral and oxidized products: Homoacetate production.

[17]MASASHI SETO, KAZUHIDE KIMBARA, MINORU SHIMURA, TAKASHI HATTA, MASAO FUKUDA, AND KEIJI YANO (1995): A Novel Transformation of Polychlorinated Biphenyls by Rhodococcus sp. Strain RHA1. In APPLIED AND ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY 61 (9), p. 3353–3358.

[18]Qian Ma (2015): The proteomic and metabolomic analyses of the consortia for vitamin C fermentation. Tianjin university.

[19]Warrens AN, Jones MD, Lechler RI (1997) Splicing by overlap extension by PCR using asymmetric amplification: An improved technique for the generation of hybrid proteins of immunological interest. Gene 186:29–35.