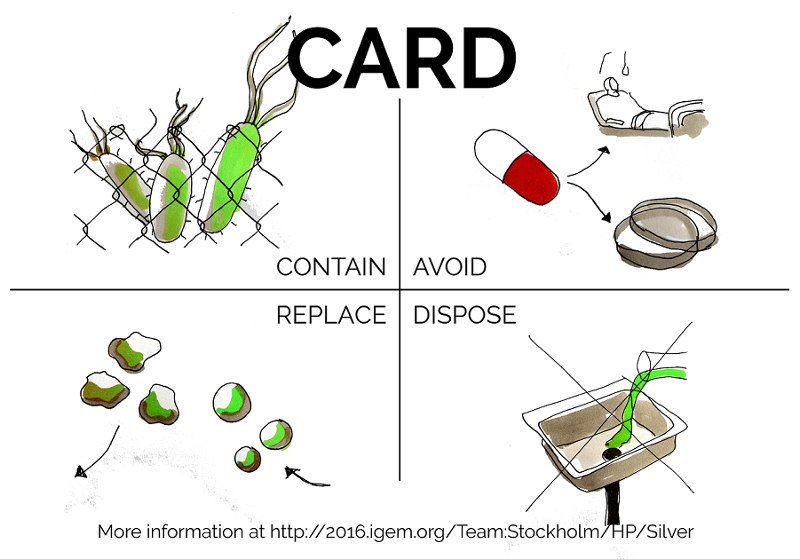

Human Practices - CARD

'A ticking time bomb’

Antibiotic resistance is without doubt one of the biggest threats of our times, with the potential to impact every aspect of our lives, from water supply systems to primary medical care. Labelled ‘a ticking time bomb’ by the UK’s chief medical officer, antibiotic resistance is predicted to cause more deaths than cancer by 2050 [1] [2].

Antibiotic resistance is intrinsically tied to our project and our project design - after all the idea of targeting biofilms rather than the bacteria themselves emerged because of our concerns about inducing resistance development with bactericidal treatments. While researching the causes and the nature of antibiotic resistance more in depth, one key aspect of it was repeatedly emphasized: antibiotic resistance is a population-based issue and it is up to each one of us to minimise the negative impact we make. Therefore, we delved further into the issue to find out how we could make a difference.

The emergence of wide-spread antibiotic resistance is often blamed on two key factors: overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Both components are often encountered in human medicine as well as agriculture and veterinary practise [3]. Whereas they might be the major cause of antibiotic resistance and prevention strategies have been laid out by a variety of national and international organisation such as the WHO and the CDC, the use of antibiotics in biotechnology is rarely discussed in this context. It is, however, a big part of a daily routine for many of us – be it to prevent contamination of our cell lines or to select successfully transformed bacteria. By adapting our use of antibiotics in research we at iGEM Stockholm believe that all of us can make a difference!

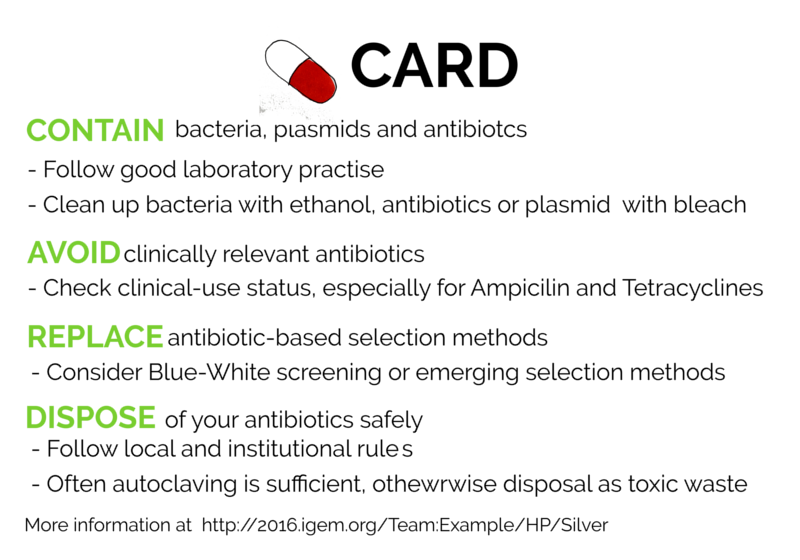

A CARD up our sleeves against antibiotic resistance

CARD is a simple system that proposes guidelines for the use of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria in the areas of life sciences, biotechnology and genetic engineering. By following four basic considerations any researcher can do their part in preventing a further spread of antibiotics resistance.

During discussion within our team and with fellow researchers, we found that many of us were woefully unaware of anything beyond the most basic safety considerations for working with antibiotics and antibiotic resistant organism in labs.

To abrogate this, we created CARD - a card up our sleeves against antibiotic resistance, based on four simple concepts: Contain, Avoid, Replace, Dispose

CARD serves as a short and easy primer for how to safely design and conduct projects involving antibiotics in biotechnology, developed for our team well as for any student and researcher in biotechnology. We have high hopes for CARD that go well beyond our iGEM project and serve to lead to safer research in our home universities and elsewhere. However, we do not aim to give a comprehensive overview of legislation or national / institutional regulations which may differ widely from each other and from best practice.

Contain your bacteria, plasmids and antibiotics

This simple step often happens to be overlooked or neglected even by experienced researchers but actually constitutes the solid base for limiting the contribution of our research to the spread of antibiotic resistance.

When considering the issue of containment in more detail, however, the question of decontamination becomes more complicated. Ideally, we want to remove three main contaminants, each one of them capable of driving antibiotic resistance development in the environment:

- Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria

- Plasmids carrying antibiotic resistance

- Antibiotics

Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria

Compared with other contaminants, bacteria can be removed relatively easily. Whereas this process is obviously never 100% efficient, the majority of the popular strains used for cloning are effectively killed off by common sterilisation solutions such as 70 % ethanol [4]. Whereas there is evidence for certain organisms exhibiting a decreased sensitivity to antiseptics, the concentrations used are generally still multitudes higher than what those organisms can withstand. It is worth to note, however, that most antiseptics are not sporicidal [5] [6]. Generally, you should [7]:

- Wash your hands when entering and leaving the lab

- Wear lab coats and gloves when handling any kind of organism, in particular if this organisms is known to carry antimicrobial resistance genes

- Decontaminate the surface you have worked on, as well as any equipment you have used

Additionally to classic containment strategies, new mechanisms to avoid the spread of recombinant bacteria are being developed, such as kill switches [8].

Plasmids

Free plasmids can, in comparably rare cases, be taken up by bacteria in a process called ‘natural transformation’ [9].

To avoid the spread of antibiotic resistance genes, any plasmids containing them should be degraded as completely as possible.The efficacy of denaturation alone in reducing plasmid transformation has been shown to vary greatly depending on the composition of the solution. This finding puts into the question the established routine of treating plasmid-contaminated waste by autoclaving alone [10] [11].

Commonly used sterilizing agents generally have little to no effect on DNA but a variety of commercial DNA contamination solutions are available and household (hypochlorite-based) bleach has also been shown to be quite effective [12]. For surfaces and instruments, UV irradiation is another established method [13]. However, the basis of avoiding plasmid contaminations remains good laboratory practise - minimising spills and working in a well contained environment.

- Minimise spills and work clean

- Surfaces and instruments: Hypochlorite bleach, commercial DNA-decontamination solutions, UV-irradiation

- Waste: Autoclaving in controlled conditions

Antibiotics

Antibiotics themselves should be handled with care and te containment strategies as outlined above are applicable as well. Whereas autoclaving or disposal in chemical waste are preferable for antibiotic solutions, smaller spills can be sufficiently well cleaned-up with a commercial bleach solution [14] [15].

Antibiotics differ widely in their character and in any potential harmful effects (details are usually provided by the retailer) but to contain them as well as help limit toxic effects, it is advisable to handle powdered antibiotics exclusively in chemical hoods [16].

- Familiarise yourself with each antibiotic you are working with and and the risks associated with it

- In many cases: autoclaving for bigger volumes, bleach for smaller spills

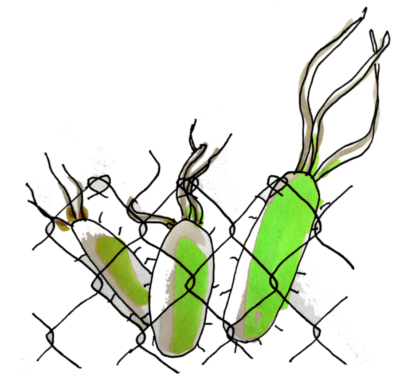

Avoid

Antibiotics can be used as selection markers and it stands to reason that the ones you pick for your experiment should not be commonly used treating infections. This way, any emerging resistance helped by the use of antibiotics will not further reduce the treatment options for infected patients in clinics. However, antibiotics used in experiments within the biotech field are sometimes still used to treat infections, more or less frequently depending on where in the world you live. Careful handling of antibiotic-transformed bacteria and optimizing safety in labs are crucial to not further drive resistance, since one of the major driving forces of resistance is the usage of the antibiotic [17]. Four antibiotics are used in the iGEM competition: Chloramphenicol, kanamycin, ampicillin and tetracycline.

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic commonly used in iGEM and in research in general. However, it is on WHO’s list of essential medicines, which are the most important medications needed in a basic health care system [18]. Chloramphenicol is mostly used in clinics in the developing world, and hould preferably only be used when other drugs are ineffective or contraindicated.

Kanamycin is another antibiotic common in iGEM, and it is also on WHO’s list of essential medicines (18). It is still being used to treat infections also in the developed world - but only if the agent is known to be caused by susceptible bacteria [19]. A third antibiotic used in research is ampicillin. Ampicillin can be used to treat infections including urinary tract infections and listeriosis. Unfortunately, but maybe not unexpectedly, bacterial resistance has been shown to increase the past years why this treatment has been excluded from urinary tract infection treatment in Stockholm, Sweden [20]. Tetracycline is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used in research and is used commonly in treating, among others, acne and pneumonia (caused by specific bacteria). Also Tetracycline is on WHO’s list of essential medicines [18].

The past decades, development and discovery of new non-resistant antibiotics has decreased dramatically. “Old and forgotten” antibiotics may have a potential of being more active against resistant pathogens in comparison to currently used ones.The 'old' antibiotics may have potential to be renewed with modern technology. Chloramphenicol, discovered in 1949 is, among others, a candidate for further clinical studies [17]. If the renewal is successful, the usage of it in research may have to be reevaluated.

A variety of antibiotics can be used as selection markers and researchers can often choose between several. We believe that it is preferable to use kanamycin or chloramphenicol, due to the more common use of ampicillin and tetracycline in the clinic for treating infections. However, depending in where on the planet you live, other antibiotics may be more common as treatment. We would like to encourage future iGEM teams to make a quick background check on the clinical-usage-status of the antibiotics where they live. This could help reducing the overlap of antibiotics in research and thereby reduce the resistance-drive.

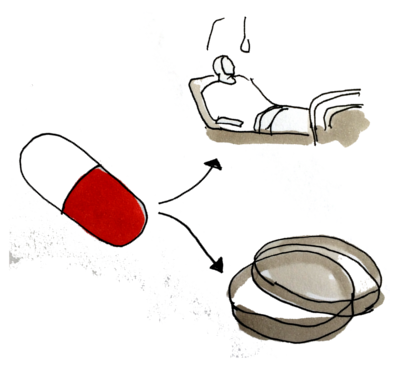

Replace

Even though antibiotic resistance is still the most commonly used selection marker in biotechnology other options are emerging for both selectable and screening markers [21] [21].

Firstly, for the mere identification of successful transformants, fairly established screening methods are available, most popular among them the blue-white screen. This method is based on successful integration of the recombinant sequence interrupting the lacZɑ gene, leading to loss of β-galactosidase. The untransformed colonies will continue producing the enzyme which catalyses the transformation of X-Gal into a blue substance while the transformants lacking the enzyme will appear white.

However, a plethora of alternatives for selection markers are also available, the most relevant ones in this context are based on either one of two principles:

- the deletion of an essential gene from the bacterial chromosome and re-introduction of the gene on the plasmid

- introduction of a negative regulator in front of an essential chromosomal gene and subsequent abrogation of the negative regulator through an element on the plasmid [21]

Unfortunately, those antibiotic-free screening methods have a major disadvantage: they are not yet sufficiently established and generally require the use of specific plasmid backbones and bacterial strains that are not available for purchase at major companies.

At this point in time, replacing antibiotic-based selection in bacterial biotechnology is a hard task to achieve with plasmids and bacterial strains for antibiotic-based screening readily available in most labs. However, times are changing: antibiotic resistance is becoming increasingly problematic, leading to tightening regulations concerning the use of antibiotics in research. Moreover, advances in biotherapeutics and food biotechnology have cause an increasing demand of safe, antibiotic-free screening techniques and will hopefully lead to well-established and characterised alternatives in the near future [22].

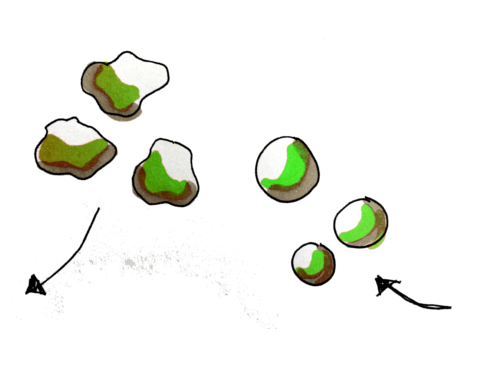

Dispose

After using antibiotics in your lab, disposing of them safely is a prime concern to avoid contact with the ecosystem [23]. Resistance development may persist long after antibiotic exposure, and cross-resistance may occur which can be difficult to foresee and handle [24]. Antibiotic waste is treated differently depending on the antibiotics' degradability [25]. Some antibiotics can be directly poured down the sink because they will break down before reaching the ecosystem whereas others should be degraded and inactivated by autoclaving or pH treatment beforehand. A third group of antibiotics is not degradable using these methods, or the characteristic is uncertain, and should be treated as hazardous chemical waste destined for incineration [25]. If the antibiotic waste contains other chemicals or organisms it must be disposed accordingly. Guidelines and regulations can vary among institutes and nations, so it is important to learn the routines where you are working.

The following table shows how to dispose some of the most common antibiotics, based on degradability. For a more extensive list, see reference [23]

| Degradability | Disposal | Antibiotics |

|---|---|---|

| Easily degradable |

In the sink* |

Ampicillin, Chloramphenicol, Penicillin |

| Inactivated by heat |

Autoclaving before disposal in the sink |

Gentamycin, Tetracyklin, Erytromycin |

| Withstands heat / autoclaving |

Hazardous, disposal as toxic waste |

Kanamycin, Ciprofloxacin, Vankomycin |

*Some institutes recommend to autoclave before disposal [26]

The management of antibiotics and other drugs in the society is complex. In every handling step there is a risk of spread to the environment; during the production, transportation, usage (both clinically and in research) and waste treatment [27]. To minimize waste hazards, the antibiotic should be degraded on site or be put in sealed containers and sent straight for incineration in specific facilities.

The largest usage of antibiotics however, occurs in regular households and a smaller fraction, about 10 %, in hospitals. Drugs that are not broken down in the body are excreted through urine of feces and end up in treatment plants [28]. In the treatment plants the drugs can face three destinies: degraded, disposed into the water, or disposed in the sludge. There are different techniques to clear the water including ozone, active carbon, and UV-light combined with oxidants [28]. It would be of great benefit to reduce the amount of antibiotics. A concept derived from the SMITe treatment is that, after the biofilm has been dispersed, smaller doses of antibiotics will be required to treat infected wounds. This would thus reduce the amount of disposed antibiotics into our ecosystem.

From person, to population responsibility for antibiotic resistance

Through our in depth research into the problem of increasing antibiotic resistance, we became highly concerned at the scope of the problem and the threats resistance entails.

We considered it essential to spread the knowledge and understanding (as well as a little fear) on the subject to our peers, friends, relatives and beyond and have worked on several university- level ways of achieving this. Part of this effort is the creation of physical cards that serve as quick and easy reference for students and researchers.

Introducing the concept early on

With our nifty CARD system in production we thought it would be a great idea to embed these safety principles from the very beginning of working in a laboratory at university level and have decided to try and implement the system into the induction package for any laboratory-relevant course at our combined universities.

Applicability to other courses

In the future we hope we could expand the principle to medical students in addition, since these constitute a big cohort of the Karolinska Institute, by designing an adapted CARD with more clinically relevant information. We anticipate this would not be related to prescribing issues which are dictated by local antibiotic policy, but instead to raise awareness on hygiene practices, alternatives and additional practices for enhancing antibiotic effectiveness (i.e meticulous care of indwelling catheters and lines), disposal and human waste products and their consequences.

Furthermore, highlighting the importance of this issue to colleagues in the Toxicology courses run at our universities would be a great way to plant the seed of interest in managing antibiotic resistance in the future...and since it is a population level problem, why not approach the epidemiology and public health sciences students too?

University wide event and beyond

Ultimately, we would love to be able to organise an antibiotic resistance awareness day at our respective universities to really drive home the facts and threats of this problem, ideally partnering up with established organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO). Organisationally, this is a huge endeavour however and something we plan to focus on as an extension of our Human Practices work in iGEM, rather than as an integral component of our entry to the competition.

References

1: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/resistance-to-antibiotics-is-ticking-time-bomb-stark-warning-from-chief-medical-officer-dame-sally-8528469.html (retrieved 08.10.2016)

2: http://www.bbc.com/news/health-30416844 (retrieved 08.10.2016)

3: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs194/en/ (retrieved 08.10.2016)

4: Mcdonnell, G. & Russell, A. D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12, 147–179 (1999).

5: Fried, V. A. & Novick, A. Organic solvents as probes for the structure and function of the bacterial membrane: effects of ethanol on the wild type and an ethanol-resistant mutant of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 114, 239–48 (1973).

6: US Department of Health and Human Services. Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. Public Heal. Serv. 5th Editio, 1–250 (1999).

7: Rutala, W. A. & Weber, D. J. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008. (2008).

8: Chan, C. T. Y., Lee, J. W., Cameron, D. E., Bashor, C. J. & Collins, J. J. ‘Deadman’ and ‘Passcode’ microbial kill switches for bacterial containment. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 82–86 (2015).

9: Tsen, S.-D. et al. Natural plasmid transformation in Escherichia coli. J. Biomed. Sci. 9, 246–52

10: Esser, K.-H., Marx, W. H. & Lisowsky, T. DNA decontamination: DNA-ExitusPlus in comparison with conventional reagents. Nat. Methods 3, (2006).

11: Masters, C. I., Miles, C. A. & Mackey, B. M. Survival and biological activity of heat damaged DNA. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 27, 279–282 (1998).

12: Fischer, M. et al. Efficacy assessment of nucleic acid decontamination reagents used in molecular diagnostic laboratories. PLoS One 11, 1–9 (2016)

13: Cone, R. W. & Fairfax, M. R. Protocol for ultraviolet irradiation of surfaces to reduce PCR contamination. PCR Methods Appl. 3, S15-7 (1993).

14: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6101a1.html (retrieved 08.10.2016)

15: http://sti.epfl.ch/files/content/sites/sti/files/shared/security/dechets-bio-1-2.pdf (retrieved 08.10.2016)

16: https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=INTERPRETATIONS&p_id=21010 (retrieved 08.10.2016)

17: Falagas ME1, Grammatikos AP, Michalopoulos A. Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008 Oct;6(5):593-600.

18: World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Model List of Essential Medicines,19th edition (April 2015). August 2015.

19: https://www.drugs.com/pro/kanamycin.html. (Retrieved 14.10.2016)

20: Giske G. Urinvägspatogenernas antibiotikakänslighet i Stockholmsregionen. Dec 2012. Retrieved on 14.10.2016 from http://www.janusinfo.se/Global/Strama/strama_urin_antibiores_121212.pdf.

21: Breyer, D., Kopertekh, L. & Reheul, D. Alternatives to Antibiotic Resistance Marker Genes for In Vitro Selection of Genetically Modified Plants – Scientific Developments, Current Use, Operational Access and Biosafety Considerations. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 33, 286–330 (2014).

22: Mignon, C., Sodoyer, R. & Werle, B. Antibiotic-Free Selection in Biotherapeutics: Now and Forever. Pathogens 4, 157–181 (2015).

23: http://www.su.se/miljo/s%C3%A5-g%C3%B6r-du/avfallshantering/labavfall/antibiotika-1.128662 2016-10-10 (retrieved 14.20.2016)

24: https://internwebben.ki.se/sites/default/files/avfall_avlopp_en_20120604.pdf (retrieved 14.20.2016)

25: http://sahlgrenska.gu.se/digitalAssets/1113/1113206_Rules_for_the_handling_of_antibiotics.pdf 2016-10-10. (retrieved 14.20.2016)

26: http://sahlgrenska.gu.se/digitalAssets/1113/1113206Rulesforthehandlingofantibiotics.pdf 2016-10-10. (retrieved 14.20.2016)

27: http://www.stockholmvatten.se/globalassets/pdf1/rapporter/avlopp/avloppsrening/lakemedelsrapport_slutrapport.pdf 2016-10-10. (retrieved 14.20.2016)

28: Wahlberg C, Björlenius B, Paxéus N. Läkemedelsrester i Stockholms vattenmiljö. Förekomst, förebyggande åtgärder och rening av avloppsvatten. Stockholm Vatten. ISBN 9789163366420