Wikiinterner Link Team:LMU-TUM_Munich/Materials (As described in the Materials section)

Wikiexterner Link Visit W3Schools

Visit W3Schools

Synopsis

Introduction

Purpose

Any cell mesh produced based on our bioink will suffer from exposition to serum-containing media or, in the case of in vivo application, the patient’s body fluids because of biotinidase. This ubiquitous enzyme is able to cleave biotin off of lysine – at a lower rate also off of intact protein. We may now shift this hydrolysis in two directions: either to prevent it altogether and thus stabilize our cell mesh, or to accelerate it to make our mesh quickly disintegrable. To this end, we must consider how biotin is linked to the proteins in our bioink.

NHS Esters as Amine Coupling Reagents

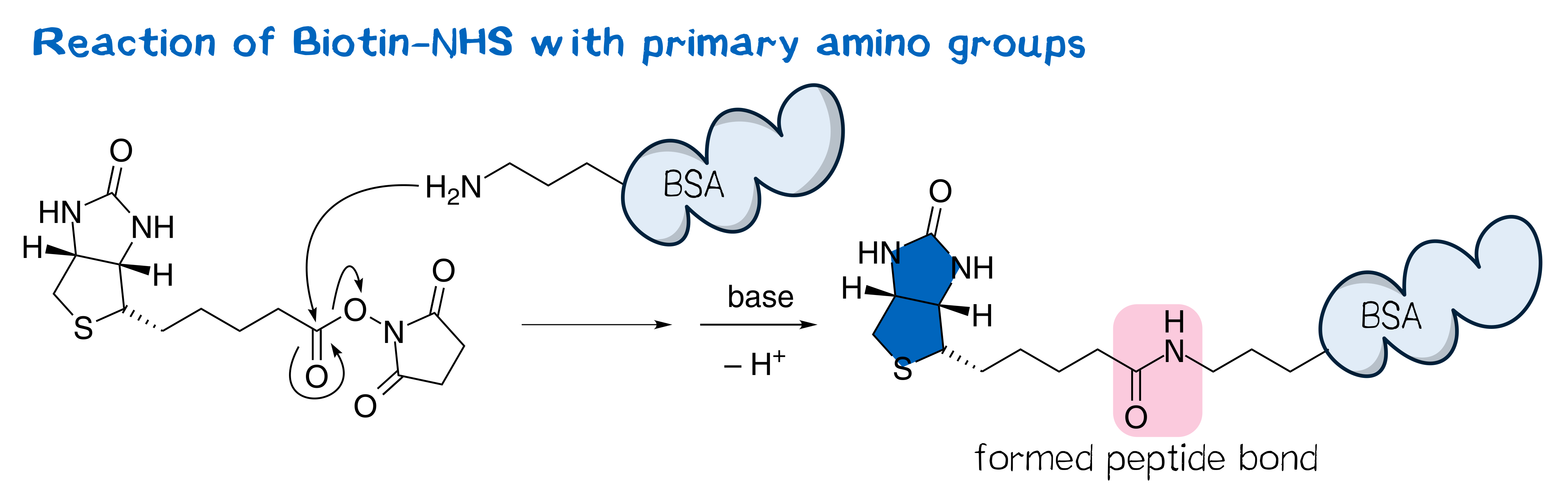

N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters belong to the group of amine-reactive active esters and are thus of great use in labeling proteins. Typically, NHS esters react with the primary amino group in the side chain of surficial lysine, forming a stable peptide bond.[1]

The utility of NHS esters was first suggested by Anderson et al.[2] in the context of peptide synthesis; nowadays, a plethora of NHS esters are widely used in bioconjugate techniques and thus commercially available, including those of many fluorescent dyes as well as that of biotin, often referred to as biotin-NHS (Figure 1).[3] NHS esters are typically synthesized from the corresponding carboxylic ester and NHS via the one-pot DCC coupling procedure[1] and purified by crystallization[2][3].

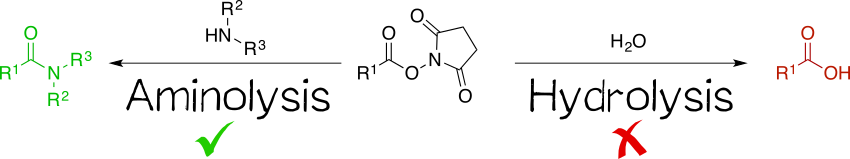

Being amine reactive, NHS esters undergo an SN2t reaction with primary or secondary amines to afford an amide bond as well as free NHS (Scheme 1, left). While this aminolysis pathway is also used in chemical synthesis, e.g. of peptides, it is key for the above-mentioned protein-labeling capability of NHS esters. The latter, however, strictly requires aqueous reaction media, so that the undesirable hydrolysis, i.e. reaction with water to give the no longer reactive carboxylic acid (Scheme 1, right), becomes a considerable side reaction even though reaction with amines, being more nucleophilic, is favored. At pH 7.0 and 0 °C, for instance, hydrolysis half-life is 4 to 5 h. For this reason, protein labeling must needs employ a great excess of NHS ester.[1][2][4][5]

For applications routinely requiring derivatization of primary amines, NHS esters are advantageous for a number of reasons. Anderson et al.[2] describe that they are highly reactive and thus give good yields in amine couplings; moreover, being crystalline, they are easy to handle. Good yields persist even when conducting the coupling reaction in the presence of water, which sets NHS esters apart from several other active esters.[4] An important benefit of NHS esters is that, in their crystalline form, they are relatively resistant to hydrolysis and thus the concomitant inactivation, meaning that they can be stored for an extended period of time under dry conditions without special precautions while retaining their activity.[3] However, this comes with a caveat: solutions of NHS esters are susceptible to hydrolysis especially if prepared in N,N-dimethylformamide or dimethyl sulfoxide. These hygroscopic solvents tend to draw moisture, promoting hydrolysis of the NHS ester; such solutions should thus be prepared immediately before use.[6]

In our work, NHS esters containing a biotin moiety, biotin-NHS among them, are used to biotinylate inanimate protein components of bioink or reservoir, for instance PAS-Lysine. For the printed mesh to be stable, this covalently attached biotin must not be cleaved. In this respect, however, we now encounter a challenge: our printing system involves live cells. These cells require cell culture media, which commonly contain serum – and serum contains the potential downfall to mesh stability: the enzyme biotinidase.

How Stable is Biotin Coupled to Proteins?

Biotinidase Hydrolytically Cleaves Biotin Off of Proteins

In the human body, biotin is a vital cofactor for several carboxylases, where it is attached to the ε-amino group of a lysine residue within the conserved sequence AMKM.[7][8] To liberate this covalently attached biotin, biotinidase, or biotin-amide amidohydrolase (EC 3.5.1.12), naturally hydrolyzes biocytin (ε-N-biotinyllysine) to biotin (vitamin H) and lysine.[7][9] The monomeric enzyme of size 76 kDa possesses a catalytic sulfhydryl group that is susceptible to inhibitors that compromise this functionality, including iodoacetamide, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, and hydroxymercuribenzoate.[7][10] It not only serves to recycle biotin for renewed usage as well as to make protein-bound biotin in food bioavailable,[9] but also acts as a shuttle for biotin within the body[11]. Biotinidase deficiency thus causes multiple carboxylase deficiency, which, for one, entails serious developmental retardation because the body lacks the free biotin necessary to replenish its holocarboxylase pool; effective treatment is easily accomplished by administering daily doses of free biotin.[8]

Biotinidase is ubiquitous throughout the human body. Its specific activity is highest in serum (5.80±0.89 nmol min–1 mL–1[12]), followed by other organs including the liver, where the enzyme is produced.[8]

While biotinidase used to be considered fairly specific for biocytin,[9] evidence has accumulated that this is not the case[13]. Thus, it can also hydrolyze other biotin amide or ester conjugates, such as the methyl ester[14] or the conjugate with p-aminobenzoate, which forms the basis of a colorimetric activity assay[9][10].

Biotinidase is thought to primarily act on biocytin or small biotin-bearing oligopeptides in vivo, since its activity rapidly diminishes with increasing peptide length; it is ultimately unable to cleave biotin off of holocarboxylases.[7] However, other studies have shown that the enzyme is capable of acting on intact proteins, such as biotinylated IgG[15] and histones[16]. Since biotin participates in the chemical reaction catalyzed by carboxylases and is thus somewhat shielded, this discrepancy likely stems from different exposure to the surrounding medium.

The issue is this: With all biotin attached to lysine on both cell receptors and spacer molecules, we will invariably face slow hydrolysis if a cell mesh is exposed to serum-containing media or applied in vivo. Depending on the task at hand, we might desire our mesh to either be stable long-term or to be disintegrated more quickly. The bonding mode of the spacer’s biotin, which is introduced chemically, is key for driving this in either direction.

Biotinidase-Resistant Biotin Conjugates

If we are to prevent biotinidase from cleaving biotin off of biotinylated components in our bioprinting system and thus from disintegrating our mesh while simultaneously obviating use of special serum-free media, we must consider how to render the biotin bound to the spacer peptide non-hydrolyzable by biotinidase.

Biotinidase-resistant biotin conjugates have been extensively studied in the context of the cancer treatment "pretargeting" approach. Here, biotinylated IgG is bound to the tumor followed by sequential treatment with streptavidin and radionuclide-containing biotin, which offers the advantages of fast accretion as well as clearance combined with low tissue retention.[15][17] The general consensus is that steric hindrance at and adjacent to the peptide bond to be cleaved is paramount; for instance, p-aminobenzoate is cleaved off much faster than the m-isomer, and the o-isomer is not cleaved at all. Thus, resistance is acquired either if the amide nitrogen is tertiary, e.g. carrying an additional methyl group (as in biotinyl-sarcosine), or if the position next to this nitrogen carries a substituent.[18] Among the reported non-hydrolyzable biotin derivatives are those with the following substituents adjacent to the amide nitrogen: hydroxymethyl (serine), carboxylate (aspartate), ethyl (2-aminobutyric acid), isopropyl (valine), benzyl (phenylalanine); a methyl group (alanine), however, is not sufficient.[13][9]

Since increased steric bulk diminishes the affinity of streptavidin toward the biotin, the 2-aminobutyric acid derivative has been preferred over e.g. the valine conjugate because it binds to streptavidin more strongly and is less lipophilic. However, this deviation may not ultimately be relevant given the inherent exceptionally high avidity of streptavidin toward biotin.[13]

Inducing Faster Enzymatic Debiotinylation?

To our knowledge, there have been no reports on how to improve the hydrolysis rate of biotinidase acting on intact proteins. We assume that the reason for the slowed or nil rate as opposed to biocytin is steric hindrance, which tallies with the prerequisites for biotinidase resistance outlined above. Thus, we must consider how to render the spacer peptide-bound biotin more accessible to the enzyme. Introducing an additional spacer molecule between biotin and the target peptide’s lysine residue should increase the distance of the hydrolyzable amide bond to the bulk peptide and thus facilitate hydrolysis.

Design

Based on the considerations outlined above, we synthesized three biotin NHS esters for covalent modification of target proteins:

- (+)-biotin NHS ester, the standard derivatizing reagent;

- (+)-biotinyl valine NHS ester, which should afford biotinidase-resistant biotinylation; and

- (+)-biotinyl aminocaproic acid NHS ester, which should afford biotinylation more susceptible to cleavage by biotinidase.

The first was designed as non-hydrolyzable: it is known to be biotinidase resistant [13]. The second was conceptualized as an accelerator of biotinidase-mediated hydrolysis: Introducing a spacer between the protein and the peptide bond to be cleaved should entail increased exposure and thus facilitate cleavage. In emulating the natural biotinidase cleavage site, biotinyllysine-NHS immediately comes to mind; however, synthesizing this derivative is impossible without a protecting group on lysine’s α-nitrogen. To obviate protection and deprotection, aminocaproic acid, which is identical to lysine in structure except that it lacks the α-nitrogen, was chosen as the spacer moiety. While some sources cite this spacer as biotinidase resistant[9], it has been shown to be hydrolyzed in in vivo applications[19].

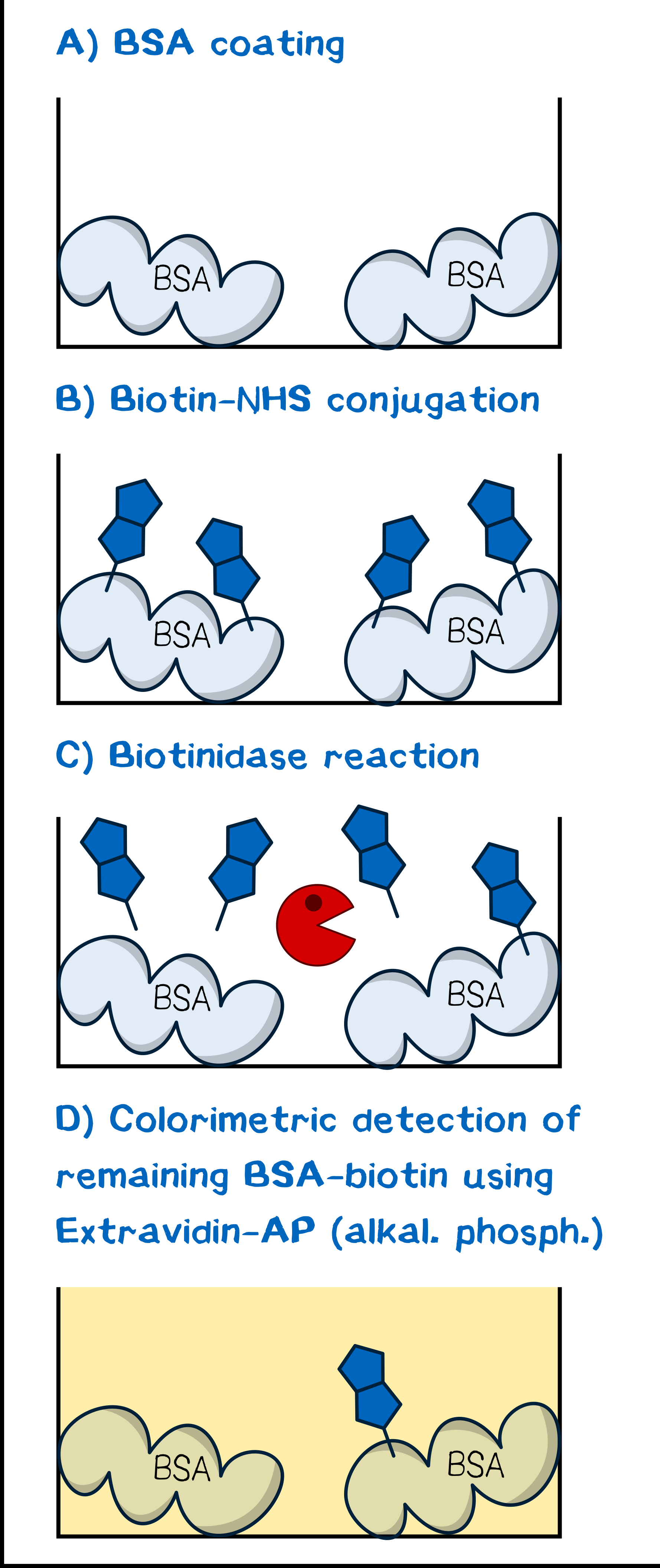

The assay was conceptualized for maximum simplicity and convenience. As is described in the literature for tests of biotinidase cleavage[13][15], we utilized human plasma as a reagent to obviate cumbersome isolation of the enzyme as described by Chauhan et al.[18]. Our model protein for debiotinylation was serum albumin coated to a 96-well plate and subsequently biotinylated chemically with biotin-NHS or a derivative. Debiotinylation was thus simply evaluated by incubating for a given time with human plasma, and the level of biotinylation was determined via adsorption of ExtrAvidin-Alkaline Phosphatase and the concomitant activity in converting p-nitrophenyl phosphate to p-nitrophenol, which can be detected spectrophotometrically.

Experiments

Syntheses

General. All chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received. For solvent evaporation, the reaction mixture was heated in a silicon oil bath on a hotplate, keeping the desired temperature via a dipped-in contact thermometer. Thin layer chromatography, used to evaluate product purity, employed silica gel plates and the solvent mixture dichloromethane–methanol 10:1, and spots were visualized by dipping in Mostain and heating shortly using a heat gun. The following abbreviations will be used: DCC, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; DMSO-d6, deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide; NHS, N-hydroxysuccinimide.

General Procedure for Synthesizing N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters from (+)-Biotin and Derivatives (GP1). The starting material carboxylic acid (1.0 eq) was suspended in dry DMF and dissolved by heating. After cooling to room temperature, NHS (1.2 eq) and DCC (1.3 eq) were added to the solution. The reaction was stirred for 19 h at room temperature. The precipitate was filtered off, and the filtrate was concentrated at 95 °C under high vacuum.

General Procedure for Synthesizing N-(+)-Biotinyl Amino Acids (GP2). To a solution of the amino acid (1.61 mmol, 1.1 eq) in water, a solution of 1 (500 mg, 1.46 mmol, 1.0 eq) in DMF (15 mL) was added dropwise over a period of 5 min. After adding triethylamine (408 μL, 296 mg, 2.93 mmol, 2.0 eq), the reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The solvent was removed under high vacuum at 95 °C, and the crude residue was washed with water to afford the desired peptide.

(+)-Biotin N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (BNHS, 1). Prepared according to GP1 using (+)-Biotin (5.00 g, 20.5 mmol) in 150 mL DMF, dissolved at 85 °C h to afford a clear, faintly yellow solution; NHS (2.83 g, 24.56 mmol); and DCC (5.49 g, 26.61 mmol). Within 30 min of adding DCC, the reaction mixture started turning opaque. The crude solid was triturated by stirring for 5 min in boiling isopropanol (200 mL) to give a suspension of fine white powder, which was collected by filtration after cooling to room temperature. White powdery solid (6.29 g, 18.42 mmol, 90%). The purity of this compound was confirmed by thin layer chromatography and 1H NMR in DMSO-d6. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 6.42 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), 4.35 – 4.27 (m, 1H), 4.19 – 4.11 (m, 1H), 3.16 – 3.05 (m, 1H), 2.86 – 2.78 (m, 6H), 2.67 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.58 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H), 1.73 – 1.34 (m, 6H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 170.2, 168.9, 162.6, 61.0, 59.2, 55.2, 40.2, 30.0, 27.8, 27.6, 25.4, 24.3 ppm. The spectroscopic data are consistent with previous reports.[20]

N-(+)-Biotinyl threonine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (BTNHS, 4). Prepared according to GP1 using 2 (373 mg, 1.08 mmol) in 24 mL DMF, dissolved by carefully heating with a heat gun to afford a homogeneous, slightly opaque solution; NHS (149 mg, 1.30 mmol); and DCC (290 mg, 1.41 mmol). The sticky crude solid was recrystallized from isopropanol (15 mL) to give a suspension of white flaky solid, which was collected by filtration after cooling to room temperature; white sticky gum (146 mg, 330 μmol, 31%). The purity of this compound was confirmed by thin layer chromatography.

N-(+)-Biotinyl aminocaproic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (BCNHS, 5). Prepared according to GP1 using 3 (385 mg, 1.08 mmol) in 24 mL DMF, dissolved by carefully heating with a heat gun to afford a homogeneous, slightly opaque solution; NHS (149 mg, 1.30 mmol); and DCC (290 mg, 1.41 mmol). The crude solid was triturated by stirring for 5 min in boiling isopropanol (15 mL) to give a suspension of fine white powder, which was collected by filtration after cooling to room temperature. White powdery solid (302 mg, 665 μmol, 62%). The purity of this compound was confirmed by thin layer chromatography and 1H NMR in DMSO-d6. 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 7.74 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 6.41 (s, 1H), 6.35 (s, 1H), 4.33 – 4.27 (m, 1H), 4.16 – 4.09 (m, 1H), 3.13 – 3.06 (m, 1H), 3.01 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.86 – 2.77 (m, 5H), 2.65 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.58 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 2.04 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.67 – 0.96 (m, 12H) ppm. 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ = 171.8, 170.2, 168.9, 162.7, 61.0, 59.2, 55.4, 38.0, 35.2, 33.3, 30.1, 28.6, 28.2, 28.0, 25.4, 25.3, 24.4, 24.0 ppm.

N-(+)-Biotinyl valine N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (BVNHS, 4). Prepared according to GP1 using 4 (195 mg, 569 mmol) in 4 mL DMF; NHS (78.6 mg, 683 μmol); and DCC (153 mg, 740 μmol). The sticky crude solid was dissolved in hot isopropanol (15 mL) and after cooling to room temperature, the product was precipitated by adding 70 mL diethyl ether. White powdery solid (146 mg, 330 μmol, 31%). The purity of this compound was confirmed by thin layer chromatography.

N-(+)-Biotinyl threonine (BT, 2). Prepared according to GP2 with threonine (192 mg) in water (3 mL). The reaction mixture turned opaque while adding the BNHS solution. White solid (410 mg, 1.19 mmol, 81%).

N-(+)-Biotinyl aminocaproic acid (BC, 3). Prepared according to GP2 with aminocaproic acid (211 mg) in water (2 mL). The reaction mixture turned opaque while adding the BNHS solution. White solid (421 mg, 1.18 mmol, 80%).

N-(+)-Biotinyl valine (BV, 2). L-Valine (206 mg, 1.76 mmol, 1.20 eq) was dissolved in a solution of sodium hydrogen carbonate (369 mg, 4.39 mmol, 3.00 eq) in water (10 mL). Acetone (15 mL) and DMF (2 mL) were added, followed by 1 (500 mg, 1.47 mmol, 1.00 eq). The reaction was stirred for 16 h at room temperature before removing the solvent under high vacuum at 60 °C. The residue was re-dissolved in water (35 mL). The solution was acidified to pH 2.0 using 1 M HCl. The precipitate was filtered, washed with 1 M HCl (50 mL), and dried under high vacuum at 50 °C. White solid (290 mg, 842 μmol, 57%).

Debiotinylation Assay

Principle

NHS Reagent Solutions. NHS esters were pre-dissolved in dry DMF (10 mM, or 1 mM for experiments with BCNHS after calibration), and the appropriate volume was added to PBS to give the target biotinylation concentrations. For the concentration series, solutions were prepared for the maximum concentration (100 μM for BNHS and BCNHS, 800 μM for BTNHS); the series was subsequently prepared in a separate 96-well plate by transferring half (200 μL) of the vigorously mixed solution in one well to the next well’s PBS (200 μL) across 12 columns, discarding 200 μL of the last to obtain 200 μL in each well. The contents of this plate were then transferred to an albumin-coated plate.

Plate Preparation. 96-well MaxiSorp plates were coated with albumin fraction 5 (0.5 mg mL–1 in PBS, 300 μL per well) for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently washed with PBS-T 0.1 (3×300 μL per well). If not directly used, the plate were stored dry at 4 °C. For biotinylation, each well was incubated with a PBS solution of the appropriate NHS ester at a given concentration for at least 45 min at room temperature, then washed with PBS-T 0.1 (3×200 μL per well).

The Assay. Debiotinylation was assessed by incubating each well with human plasma anticoagulated with heparin (200 μL) for a specified length of time. The plate was then washed with PBS-T 0.1 (3×200 μL per well). Subsequently, the well was incubated with ExtrAvidin-Alkaline Phosphatase (ExtrAvidin-AP; x M) in AP buffer (100 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2) for 30 min followed by washing with PBS-T 0.1 (3×100 μL per well). The activity of bound ExtrAvidin-AP, and thus the biotinylation level, was evaluated by adding p-nitrophenyl phosphate (0.5 mg mL–1 sodium salt hexahydrate in AP buffer) and measuring the absorbance increase at wavelength 405 nm, corresponding to generation of p-nitrophenol by the action of AP, in increments of 20 s for 10 min. For each experiment, mean slope and slope error were calculated.

Calculating Slope and Its Error

We require a readout of the initial slope dA405/dt as well as its error. Errors were assumed solely as the standard deviation of identical experiments; errors of other parameters (e.g. time and concentration) were neglected. For a set of identical wells, the slope of the kinetic curve from 0 – 1 min was determined by linear regression for each well using the formula dA405/dt =[ n · ∑(ti A405,i) – ∑ti · ∑A405,i] · [n · ∑(ti2) – (∑ti)2]–1, where n is the number of data points and the sums include all values i = 0 through n.[21] We then calculate the arithmetic mean and the standard deviation of the identical wells' slopes to obtain the desired readout dA405/dt and its error, both in units of s–1.

Results

Syntheses

Biotin-NHS (BNHS) was afforded as a white powdery solid in 90% yield and high purity judging by thin layer chromatography (TLC) and 1H NMR in DMSO-d6.

The N-biotinyl amino acid derivatives N-biotinyl threonine (BT) and N-biotinyl aminocaproic acid (BC) were obtained as white powdery solids in 81% and 80% yield, respectively. The purity of these compounds was confirmed by TLC.

N-biotinyl threonine NHS ester (BTNHS) was obtained as a white gum in 31% yield (25% for 2 steps starting from BNHS) in reasonable purity with traces of BNHS judging by TLC. NMR analysis was impossible because the compound was insoluble in any available NMR solvent (DMSO-d6, CDCl3, MeOD; D2O is incompatible because of hydrolysis). N-biotinyl aminocaproic acid (BCNHS) was obtained as a white powdery solid in 62% yield (50% for 2 steps starting from BNHS) in high purity judging by TLC as well as 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and COSY in DMSO-d6.

Calibrating the NHS Ester Concentrations for Biotinylation

To determine a suitable concentration for follow-up experiments, we assayed a concentration series of each biotinylation reagent in duplicates starting from 100 μM (BNHS and BCNHS) or 200 μM (BVNHS) and diluting 1:2 in the next set of wells across one row (12 wells), and calculated the slope and its error for each set of two identical wells. This slope corresponds to the activity of ExtrAvidin-AP immobilized in the well and thus to the biotinylation level.

With dA405/dt plotted against c, the initial slope of this curve is steepest before leveling out toward higher concentration. As such, the data appear to form a saturation curve, albeit less pronounced in the case of BVNHS. In the semilogarithmic plot of dA405/dt against log c, the graphs of BVNHS and BNHS are apparently exponential; however, the slope of the BCNHS curve is sigmoidal around an approximately linear central range.

Interestingly, the development of the concentration series' data points differs significantly between the three derivatives: Compared to the standard BNHS, BCNHS affords a steeper curve that reaches the same ExtrAvidin-AP activity at lower reagent concentrations and that appears to also achieve a higher absolute activity, i.e. a higher biotinylation level. Conversely, BVNHS has a drastically diminished increase in ExtrAvidin-AP activity with rising reagent concentration, achieving a biotinylation equivalent to 1 μM of BNHS and BCNHS only at 200 μM.

Discussion

Syntheses: Performance and Mechanistic Considerations

Synthesizing Biotin-NHS: General DCC Coupling Chemistry

Synthesis of (+)-biotin N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (BNHS, 1) was adapted from Götz et al.[22] The reaction proceeds via a straightforward carbodiimide coupling procedure between (+)-biotin as the carboxylic acid and NHS, being an N-hydroxylamine, as the hydroxyl group-bearing component (Scheme x).

The reaction involves two main steps: first, the acid’s carboxyl group conducts a nucleophilic attack on the carbodiimide carbon, resulting in an O-acylisourea intermediate after proton transfer; second, the coupling partner’s hydroxyl group in turn attacks the now activated carboxyl carbon in an SN2t reaction followed by proton transfer, yielding the desired NHS ester as well as the byproduct dicyclohexylurea, which is sparingly soluble in DMF and thus for the most part precipitates out of solution[22][23]. As such, a large part of this byproduct is easily removed by filtering the reaction mixture before removing the solvent.

DCC coupling reactions are reportedly frequently encumbered by the desired, activated intermediate O-acylisourea rearranging to the no longer reactive N-acylurea[23] (Scheme x), especially when using DMF as the solvent[24]. Nevertheless, this does not pose a problem in coupling reactions with NHS: the latter reacts with the O-acylurea so fast that rearrangement is effectively suppressed.[25] Incidentally, the Steglich esterification makes use of this same principle that adding a good nucleophile – 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) in the typical procedure – to DCC coupling reactions streamlines the reaction progress toward the desired product.[26]

Boiling the crude solid in isopropanol serves to purify the target compound, as this solvent dissolves remaining dicyclohexylurea[23] and NHS[27]. Provided that the isopropanol is dry, the NHS ester is not compromised by this procedure, being reasonably stable toward alcohols; even methanolysis – with methanol being much less sterically demanding than isopropanol – requires several days at elevated temperatures to complete.[28][29]

BNHS was obtained as a white, powdery solid in 90% yield and good purity (TLC, 1H NMR). Judging by the relative peak integrals of biotin and NHS moiety, the product contains some biotin, and the slightly elevated integral of the aliphatic peaks indicates that trace isopropanol may be left from trituration.

Synthesizing N-Biotinyl Amino Acids: Mechanism of Aminolysis

Adapted from Bellia et al.[30] and Wilbur et al.[13], BNHS served as the starting material for synthesizing the target NHS esters of biotin derivatives with the amino acids aminocaproic acid and threonine. The mechanism of peptide bond formation proceeds via an SN2t reaction at the active ester[5] with NHS as the leaving group (Scheme 3).

While the reaction could proceed without added base triethylamine, this accelerates the reaction.[5] We must needs consider the efficiency of this coupling reaction, seeing as the amino acid is pre-dissolved in water. Under these conditions, the desired aminolysis and the non-productive hydrolysis become competing reactions, especially since both are faster in the presence of base.[5] Besselink et al. investigated the relative rates on N-Boc-protected amino acid NHS esters in a solvent mixture of DMSO and water, concluding that hydrolysis only becomes appreciable if water content exceeds 30%.[31] With a maximum of 3 mL water in 15 mL DMF, our experimental setup never surpassed 17%, so that the desired biotinyl amino acid is expected to be the major product.

Coupling with aminocaproic acid is fairly straightforward, since the carboxylate group is much less nucleophilic than the amine and as such does not interfere with the reaction. Nevertheless, we should briefly consider the selectivity of coupling with threonine, which contains an additional hydroxyl group. Intuitively, we expect the amine to react preferentially, since it is more nucleophilic than the alcohol; indeed, as mentioned above, NHS esters react only slowly with alcohols.[28][29] Thus, both coupling reactions should yield the desired biotinyl amino acid as the main product.

Purification of these target compounds is easily achieved by washing the crude product with water, since they are not well soluble; as such, trace biotin derived from hydrolysis and NHS, the byproduct, are removed.[2][32] Triethylamine is removed with the solvent while heating under high vacuum.

Both derivatives were afforded as white, powdery solids similar to BNHS in 80% (BCNHS) and 81% (BTNHS) yield and good purity (TLC).

Synthesizing N-Biotinyl Amino Acid NHS esters: The Targets

Mechanistically, DCC-mediated coupling of the biotinyl amino acids with NHS proceeds in the same way as described above for synthesis of BNHS.

NMR Spectrometry: Analyzing Product Purity

NMR data for BCNHS confirmed the purity of this compound in that (a) all integrals give integer values when integrating distinct peak groups of biotin and aminocaproic acid moieties as well as the NHS singlet and setting the integral of the biotin multiplet at 4.33 – 4.27 ppm to 1.00. This indicates that the compound contains biotin, aminocaproic acid, and NHS in equivalent amounts, as is expected for pure BCNHS. Subinteger values of either constituent would suggest that only part of the product is the target compound; for instance, if an aminocaproic acid peak corresponding to one proton were to integrate to 0.70 with reference to the above-mentioned biotin peak, we would infer that the compound contains excess free biotin not bound to aminocaproic acid; and (b) the triplet belonging to the aminocaproic acid nitrogen’s proton appears at high shift characteristic of an amide, showing that the peptide bond in BCNHS is present.

For further characterization, we acquired a COSY spectrum. This two-dimensional NMR measurements correlates protons separated by three bonds, i.e. protons attached to adjacent framework atoms, and thus allows us to assign peaks in 1H NMR to specific protons with greater confidence. Figure x shows the COSY correlations as well as the peak shifts and multiplicities thus assigned.

We find all correlations expected for biotin’s bicyclic moiety. Interestingly, the two protons attached to the CH2 group next to the sulfur atom appear at different shifts, and COSY shows that they couple with each other. As such, they are not chemically equivalent. Even though in most cases geminal protons are equivalent, non-equivalency is commonly observed in conformationally fixed ring systems. Likewise, biotin’s favored conformation fixes one of these protons in the axial and the other in the equatorial position,[33] and the permanently different electronic environments conferred by this positional distinction translate into different chemical shifts. The shift assignment to equatorial and axial proton was taken from Bates et al.[34].

Other correlations clearly seen in COSY are those between the protons of (a) the side chain’s first carbon and the ring carbon it is attached to; (b) the position α to the amide carbon and the adjacent aliphatic CH2 group; (c) the position α to the ester carbon and the adjacent aliphatic CH2 group; and (d) the amide nitrogen and the adjacent aliphatic CH2 group. Correlations along the aliphatic chains are difficult to pinpoint since aliphatic protons do not differ much in their electronic environment and thus form a broad multiplet of superimposed peak groups at low shifts. Moreover, correlations across the amide and ester group are not visible because they span more than three bonds.

We observe three instances of unexpected coupling behavior: (a) the biotin nitrogen atoms’ protons yield singlets even though they possess vicinal protons. That they fail to couple is especially surprising since the amide nitrogen’s proton distinctly couples with the two vicinal protons (J = 5.7 Hz). This selfsame phenomenon has been addressed in the literature, without gleaning a satisfactory explanation[34]; (b) the CH2 group next to the amide nitrogen appears as a quartet, even though it should couple with both the amide proton and the adjacent CH2 group to give a triplet of doublets (td) or doublet of triplets (dt), depending on the coupling constants to either of these vicinal protons. Here, we are likely dealing with a superimposition of these multiplicities making for a pseudo quartet; (c) both the equatorial and axial protons of CH2S give doublets even though they have two coupling partners: the vicinal CH proton as well as each other. However, the latter geminal coupling has J ≈ 1, so that it is not visible in the spectrum at the resolution provided by the 300 MHz spectrometer.

Debiotinylation Assay

Finding Optimized Biotinylation Concentrations

Since the level of biotinylation, which correlates with ExtrAvidin-AP activity, is evaluated via the kinetics of PNP being generated from PNPP, we have to ensure two aspects before starting the actual experiments: (a) the kinetic curve's slope should be within the dynamic range of the experimental setup, so that a decrease in biotinylation caused by biotinidase activity results in a maximal change in slope; and (b) it should be approximately equal for all three derivatives at time point i = 0 for better comparability. This was accomplished by assaying a concentration series of each biotinylation reagent.

If we plot dA405/dt against c, we expect a saturation curve: with rising NHS ester concentration, the biotinylation level will first rapidly increase and then gradually approach a horizontal asymptote signifying full biotinylation of BSA. The semi-logarithmic plot of dA405/dt against log c transforms a saturation curve into a sigmoidal graph in which the central linear section is the target dynamic range.[35] We find both of these correlations to be true in our experimental setup, even though the sigmoidal shape is only achieved by BCNHS; the other derivatives have evidently not been tested at sufficient concentration to attain saturation.

How do we resolve the distinct differences between the concentration series? It is unlikely that differing propensity to adsorb ExtrAvidin-AP is in play: while biotinylvaline has been reported to have a decreased affinity for avidin, this was in the context of a competition assay against regular biotin.[13] In the absence of extraneous biotin, the avidin conjugate should bind even to the biotinylvaline moieties in a virtually quantitative fashion. Thus, the only factors that remain are biotinylation rate and efficiency: if one derivative were to either react more slowly with the protein or be more susceptible to hydrolysis than another, the result would be that biotinylation level increases less with rising reagent concentration or that the saturation curve's horizontal asymptote is at a lower value, respectively.

What differentiates the three derivatives that could cause such changes? The most blatant distinction is steric bulk. BNHS and BCNHS are similar, but the elongated spacer arm of BCNHS perhaps makes for more flexibility and thus slightly decreased steric hindrance. However, BVNHS is significantly more encumbered, since it bears an isopropyl group adjacent to the reactive ester carbon. Steric hindrance in NHS esters resulting in decreased coupling efficiency has been reported in the context of derivatizing a polymer containing primary amines with the NHS ester of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA-NHS): at 50 °C in N,N-dimethylacetamide in the presence of ethyldiisopropylamine (DIPEA) and the nucleophilic catalyst 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), only 5% conversion was achieved within 16 h.[36] The authors argue that, apart from the carboxylate groups of ester and polymer electrostatically repulsing each other, the NHS ester's steric bulk is to blame for this low efficiency. While electrostatics should not apply to our system, the relatively bulky isopropyl group may entail this selfsame reduced coupling efficiency; moreover, the isopropyl group being a σ donor, it may somewhat increase electron density at the reactive carbon and thus render it less electrophilic. The hydrolysis rate may also be elevated relative to the aminolysis rate, seeing as water or hydroxide are much less bulky than a lysine residue attached to protein and thus perhaps suffer less from the increased hindrance around the reactive site.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hermanson, G. T. (2013) Bioconjugate Techniques (3 ed.). Boston: Academic Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Anderson, G. W., Zimmerman, J. E., & Callahan, F. M. (1963). N-Hydroxysuccinimide Esters in Peptide Synthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 85(19), 3039-3039.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Klykov, O., & Weller, M. G. (2015). Quantification of N-hydroxysuccinimide and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide by hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC). Analytical Methods, 7(15), 6443-6448.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Anderson, G. W., Zimmerman, J. E., & Callahan, F. M. (1964). The Use of Esters of N-Hydroxysuccinimide in Peptide Synthesis. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 86(9), 1839-1842.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Kalkhof, S., & Sinz, A. (2008). Chances and pitfalls of chemical cross-linking with amine-reactive N-hydroxysuccinimide esters. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 392(1), 305-312.

- ↑ Savage, M. D. (1996). An Introduction to Avidin-Biotin Technology and Options for Biotinylation. In T. Meier & F. Fahrenholz (Eds.), A Laboratory Guide to Biotin Labeling in Biomolecule Analysis. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Craft, D. V., Goss, N. H., Chandramouli, N., & Wood, H. G. (1985). Purification of biotinidase from human plasma and its activity on biotinyl peptides. Biochemistry, 24(10), 2471-2476.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wolf, B. (2010). Clinical issues and frequent questions about biotinidase deficiency. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism, 100(1), 6-13.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Wolf, B., Hymes, J., & Heard, G. S. (1990). [11] Biotinidase. In W. Meir & A. B. Edward (Eds.), Methods in Enzymology (Vol. 184, pp. 103-111): Academic Press.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Knappe, J., Bruemer, W., & Biederbick, K. (1963). Reinigung und Eigenschaften der Biotinidase aus Schweinenieren und Lactobacillus casei. Biochemische Zeitschrift, 338, 599-613.

- ↑ Chauhan, J., & Dakshinamurti, K. (1988). Role of human serum biotinidase as biotin-binding protein. Biochemical Journal, 256(1), 265-270.

- ↑ Wolf, B., Grier, R. E., Secor McVoy, J. R., & Heard, G. S. (1985). Biotinidase deficiency: A novel vitamin recycling defect. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, 8(1), 53-58.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Wilbur, D. S., Hamlin, D. K., & Chyan, M.-K. (2006). Biotin Reagents for Antibody Pretargeting. 7. Investigation of Chemically Inert Biotinidase Blocking Functionalities for Synthetic Utility. Bioconjugate Chemistry, 17(6), 1514-1522.

- ↑ Pispa, J. (1965). Animal Biotinidase. Annales Medicinae Experimentalis et Biologiae Fenniae, 43, 1-39.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Bogusiewicz, A., Mock, N. I., & Mock, D. M. (2004). Release of biotin from biotinylated proteins occurs enzymatically and nonenzymatically in human plasma. Analytical Biochemistry, 331(2), 260-266.

- ↑ Ballard, D. T., Wolff, J., Griffin, B. J., Stanley, S. J., van Calcar, S., & Zempleni, J. (2002). Biotinidase catalyzes debiotinylation of histones. European Journal of Nutrition, 41(2), 78-84.

- ↑ Goldenberg, D. M., Chatal, J.-F., Barbet, J., Boerman, O., & Sharkey, R. M. (2007). Cancer Imaging and Therapy with Bispecific Antibody Pretargeting. Update on cancer therapeutics, 2(1), 19-31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Chauhan, J., & Dakshinamurti, K. (1986). Purification and characterization of human serum biotinidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 261(9), 4268-4275.

- ↑ Axworthy, D. B., Theodore, L. J., Gustavson, L. M., & Reno, J. M. (1999). US5955605A.

- ↑ Baschieri, A., Muzzioli, S., Fiorini, V., Matteucci, E., Massi, M., Sambri, L., & Stagni, S. (2014). Introducing a New Family of Biotinylated Ir(III)-Pyridyltriazole Lumophores: Synthesis, Photophysics, and Preliminary Study of Avidin-Binding Properties. Organometallics, 33(21), 6154-6164.

- ↑ Ogrodnik, A., Lammers, A., Kraus, D., Fox-Beyer, B., Kämmerer, P., Smith-Gicklhorn, A., . . . Grotemeyer, J. (2007). Praktikum in Physikalischer Chemie für Studierende im Grundstudium. Munich: Chairs of Physical Chemistry at Technische Universität München.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Götz, M. G., James, K. E., Hansell, E., Dvořák, J., Seshaadri, A., Sojka, D., . . . Powers, J. C. (2008). Aza-peptidyl Michael Acceptors. A New Class of Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Asparaginyl Endopeptidases (Legumains) from Evolutionarily Diverse Pathogens. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 51(9), 2816-2832.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Birr, C. (1978). Aspects of the Merrifield Peptide Synthesis. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- ↑ Rolland, M., Amblard, M., Fehrentz, J.-A., & Martinez, J. (2002). Acylation Methods. In M. Goodman, A. Felix, L. Moroder, & C. Toniolo (Eds.), Synthesis of Peptides and Peptidomimetics (pp. 774). Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

- ↑ Rich, D. H., & Singh, J. (1979). The Carbodiimide Method. In E. Gross & J. Meienhofer (Eds.), Major Methods of Peptide Bond Formation (pp. 241-245). New York: Academic Press.

- ↑ Neises, B., & Steglich, W. (1978). Simple Method for the Esterification of Carboxylic Acids. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 17(7), 522-524.

- ↑ Knight, D. W. (2001). N-Hydroxysuccinimide. e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Gao, A., Yang, X., Zhang, C., Long, G., Pu, J., Yuan, Y., . . . Liao, F. (2012). Facile spectrophotometric assay of molar equivalents of N-hydroxysuccinimide esters of monomethoxyl poly-(ethylene glycol) derivatives. Chemistry Central Journal, 6(1), 1-9.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Xie, Y., Yang, X., Pu, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Y., Xie, G., . . . Liao, F. (2010). Homogeneous competitive assay of ligand affinities based on quenching fluorescence of tyrosine/tryptophan residues in a protein via Förster-resonance-energy-transfer. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 77(4), 869-876.

- ↑ Bellia, F., Oliveri, V., Rizzarelli, E., & Vecchio, G. (2013). New derivative of carnosine for nanoparticle assemblies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 70, 225-232.

- ↑ esselink, G. A. J., Beugeling, T., & Bantjes, A. (1993). N-Hydroxysuccinimide-activated glycine-sepharose. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 43(3), 227-246.

- ↑ Kolter, T., & Möseneder, J. (2010). Biotin ROEMPP Online. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

- ↑ DeTitta, G. T., Blessing, R. H., Moss, G. R., King, H. F., Sukumaran, D. K., & Roskwitalski, R. L. (1994). Inherent Conformation of the Biotin Bicyclic Moiety: Searching for a Role for Sulfur. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 116(15), 6485-6493.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Bates, H. A., & Rosenblum, S. B. (1985). 300 Mhz 1H NMR spectra and conformations of biotin and related hexahydrothienoimidazolone derivatives. Tetrahedron, 41(12), 2331-2336.

- ↑ Invitrogen. (2006). Theory of Binding Data Analysis Fluorescence Polarization Technical Resource Guide. Madison: Invitrogen Corporation.

- ↑ Hruby, M., Skodova, M., Mackova, H., Skopal, J., Tomes, M., Kropacek, M., . . . Kucka, J. (2011). Lutetium-177 and iodine-131 loaded chelating polymer microparticles intended for radioembolization of liver malignancies. Reactive and Functional Polymers, 71(12), 1155-1159.