Contents

- 1 University Homepages

- 2 Newspapers

- 3 German Radio

- 4 Websites

- 4.1 Synbiobeta.com: "iGEM Rocks the World Once Again"

- 4.2 wired.de: "Münchner Studierende kommen dem gedruckten Herzen einen Schritt naeher"

- 4.3 BioM Biotech Cluster Development

- 4.4 Biotechnologie.de: "Team Muenchen: Mit Bio-Tinte zum iGEM-Champion 2016"

- 4.5 Biooekonomie.de - "iGEM-Finale: Auf Titeljagd in Boston"

- 4.6 3dnatives.com - "BiotINK: Bio-3D-Druck für zu Hause mit einem Ultimaker2"

- 4.7 3dprintingindustry.com - "BiotINK: Now you can print tissue with your own 3D printer"

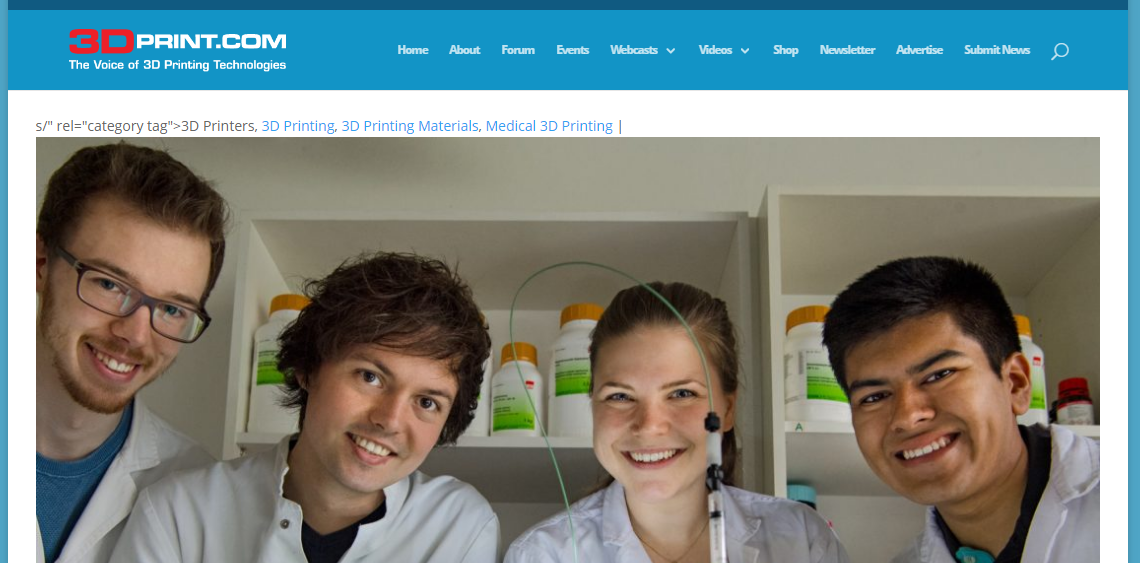

- 4.8 3dprint.com - "BiotINK: Scaffold Free Bioprinting"

- 5 Social Media

University Homepages

Webpage of the TU Munich "www.tum.de"

Press release from TUM

Joint TUM and LMU Team Win First Prize at iGEM Competition in Boston

Manufacturing Live Tissue with a 3D Printer

04.11.2016, Research news

At the international iGEM academic competition in the field of synthetic biology, the joint team of students from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU) won the first rank (Grand Prize) in the “Overgraduate” category. The team from Munich developed an innovative process which allows intact tissue to be built with the use of a 3D printer.

The international Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition encourages students from the field of synthetic biology to implement innovative ideas and to contend with their biotechnology projects. The competition, which was initiated by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has been organized by the iGEM Foundation since 2003 while the MIT campus in Cambridge, MA, hosted the event until 2014. Among the 300 finalist teams this year there were twelve from Germany, including a joint team from TUM and LMU of Munich.

The 2016 iGEM project of the year, led by Professor Arne Skerra from the Chair of Biological Chemistry at TUM and sponsored by the Research Training Group GRK2062 of LMU, examined the growing problem of insufficient donor organs in transplant medicine. “The participating students from TUM and LMU developed an innovative method that should ultimately make it possible to manufacture intact tissue, and possibly even complete organs, with the help of a 3D printer,” said Professor Skerra explaining his current project group. “This breakthrough was only made possible by a combination of synthetic biology, molecular biotechnology, protein design, and technical engineering.”

3D PLASTIC PRINTER BECOMES ‘3D BIOPRINTER’

One question the team asked was: What if the printed tissue could fulfill entirely new functions in the body, such as the production of therapeutic proteins? The printing of non-living biological material such as cartilage is already state-of-the-art. However, substantial obstacles still had to be overcome on the path to printing complex cell structures. “And this is exactly where this year's project began, in which live cells were printed into a biocompatible matrix using a 3D printer,” project head Skerra explained. For this purpose, a conventional plastic 3D printer was converted into a 3D bioprinter.

Layer by layer, biological tissue is created in this manner. In the past, hydrogels were used for such purposes — they provide a gelatinous scaffold in the first place and are populated with cells thereafter. However, the students from both Munich universities followed an alternative strategy because the ‘scaffold’ approach makes printing more complicated and the cells are held together in an unnatural manner. Instead, they developed a special bio-ink, a type of biochemical two-component resin for directly printing living cells in 3D.

The main component of this system is biotin, commonly known as vitamin H or B7, with which the surface of the cells was coated. The second component is Streptavidin, a protein that binds biotin and serves as the actual biochemical glue. In addition, bulky proteins were equipped with biotin groups to serve as cross-linker. “When a suspension of the cells is ‘printed’ into a concentrated solution of the protein components,” Professor Skerra explained, “the desired 3D structure forms.”

Hence, with this bio-ink a moldable tissue made of live cells is created in the biotINK tissue printer — more or less ready for transplantation. In light of these results, the team led by Professor Skerra and his doctoral students Andreas Reichert and Volker Morath at TUM, whose motto for the competition was “Let’s take bioprinting to the next level,” delivered what they had promised.

Webpage of the LMU faculty for biology "www.biologie.lmu.de"

[http://www.en.biologie.uni-muenchen.de/aktuelles/igem2016competition/index.html Press release from LMU]

In developing a novel approach toward bioprinting tissue, Munich student team brings world championship in synthetic biology to Germany.

Initiated by the Research Training Group GRK2062, „Molecular Principles of Synthetic Biology“, the combined iGEM team from the two Munich universities LMU and TUM has received the 2016 Grand Prize (1st place) in the international iGEM competition at Boston (MA). The team has developed a novel approach towards bioprinting based on a biomolecular two-component glue, which is composed of the protein avidin and the vitamin biotin that tightly bind to each other. This mild molecular interaction enables the printed cells to adhere to each other, opening up new perspectives for the bioprinting of live tissues and even organs.

After developing their interdisciplinary bioprinting project over the summer in the laboratory of Prof. Dr. Arne Skerra at TUM in Weihenstephan, the team was awarded the main prize of the "Overgraduate" section on November 1st, 2016. Furthermore, it won the first prize in the category "Manufacturing" and additionally received special awards for "Best Hardware" as well as "Best Software". Following up on the 4th place for LMU in 2012 and the 2nd place for TUM in 2013, this represents the greatest success for a Munich team in the iGEM competition thus far.

Congratulations to all members and thanks a lot to all sponsors of the team!

The iGEM competition is an annual, world wide, synthetic biology event aimed at undergraduate university students, as well as high school and graduate students. Multidisciplinary teams work all summer long to build genetically engineered systems using standard biological parts called Biobricks. iGEM teams work inside and outside the lab, creating sophisticated projects that strive to create a positive contribution to their communities and the world.

Webpage of the GRK2062 "www.grk2062.uni-muenchen.de"

iGEM 2016: MUNICH TEAM RECEIVES GRAND PRIZE AT iGEM JAMBOREE

In developing a novel approach toward bioprinting tissue, Munich student team brings world championship in synthetic biology to Germany.

Initiated by the Research Training Group GRK2062, „Molecular Principles of Synthetic Biology“, the combined iGEM team from the two Munich universities LMU and TUM has received the 2016 Grand Prize (1st place) in the international iGEM competition at Boston (MA). The team has developed a novel approach towards bioprinting based on a biomolecular two-component glue, which is composed of the protein avidin and the vitamin biotin that tightly bind to each other. This mild molecular interaction enables the printed cells to adhere to each other, opening up new perspectives for the bioprinting of live tissues and even organs.

After developing their interdisciplinary bioprinting project over the summer in the laboratory of Prof. Dr. Arne Skerra at TUM in Weihenstephan, the team was awarded the main prize of the "Overgraduate" section on November 1st, 2016. Furthermore, it won the first prize in the category "Manufacturing" and additionally received special awards for "Best Hardware" as well as "Best Software". Following up on the 4th place for LMU in 2012 and the 2nd place for TUM in 2013, this represents the greatest success for a Munich team in the iGEM competition thus far.

Congratulations to all members and thanks a lot to all sponsors of the team!

The iGEM competition is an annual, world wide, synthetic biology event aimed at undergraduate university students, as well as high school and graduate students. Multidisciplinary teams work all summer long to build genetically engineered systems using standard biological parts called Biobricks. iGEM teams work inside and outside the lab, creating sophisticated projects that strive to create a positive contribution to their communities and the world.

Newspapers

Sueddeutsche Zeitung: "Ein bisschen Frankenstein"

[http://www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/wissenschaft-ein-bisschen-frankenstein-1.3274096 Weblink to the article]

German Radio

DRadio Wissen: "ORGANE DER ZUKUNFT"

[http://dradiowissen.de/beitrag/kuenstliches-herz-organe-aus-dem-3-d-drucker Weblink to the article] File:Muc DeutschlandfunkWissen.pdf

"Ein Team aus Münchner Studentinnen und Studenten macht Fortschritte auf dem Weg zum gedruckten Herzen. Organe aus dem 3D-Drucker könnten in Zukunft Organspenden ersetzen.

Seit Jahren das gleiche Problem: Immer mehr Menschen benötigen zum Überleben eine Organtransplantation, aber es gibt zu wenig Spenderorgane. Allein in Deutschland sterben Tausende schwerkranke Patienten, während sie auf ein Organ warten. Studierende aus München haben nun eine Lösung gefunden. Sie drucken die Organe einfach aus. Okay, ganz soweit sind sie noch nicht, aber sie machen erste Schritte in diese Richtung.

"Wir versuchen letztendlich Zellen, also Gewebe, mit einem 3D-Drucker zu drucken. Dazu haben wir einen konventionellen Plastik-3D-Drucker umgebaut zu einem 3D-Bioprinter."

Luisa Krumwiede, Studentin an der TU München

In Boston haben die Studierenden von TU und LMU München mit ihrem 3D-Biodrucker den großen Preis der Biokonstrukteure gewonnen - als bestes von über 300 Teams aus der ganzen Welt.

Gedruckte Gewebeschichten

Um Gewebe zu drucken, geben sie Stamm- oder Bindegewebszellen in das Gerät. Die Zellen sind genetisch so verändert, dass sie Rezeptoren auf der Oberfläche haben. Damit können sie an andere Zellen andocken. Dann kommt noch eine Art Biotinte dazu. Die wirkt wie Klebstoff und bindet sich an den Rezeptor. Am Ende kommen aus dem Drucker dann miteinander vernetzte Zellen, die durch die Biotinte zusammengehalten werden. Bisher können die Studierenden mithilfe dieses Verfahrens nur dünne Gewebeschichten ausdrucken. Von einsatzfähigen Organen sind sie noch weit entfernt.

Das Verfahren der Münchener Studenten unterscheidet sich von anderen Versuchen, künstliches Gewebe herzustellen. Bisher hatten Forscher mit einer Art Gerüst aus Hydrogel - das an Wackelpudding erinnert - gearbeitet. In das können die Zellen vom Drucker eingesetzt werden. Bei diesem Verfahren nehmen die Zellen dann selbstständig Kontakt miteinander auf. Das Problem: Die Hydrogel-Methode ist aufwändig und teuer. Außerdem muss das Gel später wieder entfernt werden.

"Das Prinzip ist so gut, dass es vielleicht bald ein Patent gibt und sich irgendwann durchsetzt." Michael Lange, Wissenschaftsjournalist

Für die Studierenden aus München ist ihr Erfolg ein erster Schritt, um künstliches Gewebe herzustellen. Es gibt aber durchaus Wissenschaftler, die schon weiter sind: Kleinere Gewebe wurden schon mit Hilfe der 3D-Drucker-Technik hergestellt, zum Beispiel Knorpelgewebe für den Knorpel einer Ohrmuschel. Aber Leber und Herz - das sind viel kompliziertere Gebilde. Da muss noch etwas getüftelt werden." Gesprächspartner: Michael Lange; Moderatorin: Sonja MeschkatDeutschlandfunk: "Bio-Tinte fuer den Bio-3D-Drucker"

[http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/wissenschafts-wettbewerb-bio-tinte-fuer-den-bio-3d-drucker.676.de.html?dram:article_id=369777 Weblink to the article] File:Muc Deutschlandfunk.pdf PDF of the article.

"Bio-Tinte für den Bio-3D-Drucker

Jährlich zieht es tausende Studenten der Biologie, Biochemie und Biotechnologie nach Boston zur iGEM Competition, einem Wettbewerb für Biobastler. Unter den 300 Finalistenteams sind dieses Mal auch zwölf deutsche Mannschaften. Sie haben einen konventionellen Plastik-3D-Drucker zu einem 3D-Bioprinter umgebaut oder erforschen Krebstherapien. Von Michael Lange

Nur auf den ersten Blick ein gewöhnlicher Drucker. Der zweite Blick verrät: Gedruckt wird in drei Dimensionen. Und auch das ist noch nicht alles. Es handelt sich um einen Bio-Drucker, erklärt Luisa Krumwiede, Studierende im fünften Semester an der TU München: "Wir versuchen letztendlich Zellen, also Gewebe, mit einem 3D-Drucker zu drucken. Und dazu haben wir einen konventionellen Plastik-3D-Drucker umgebaut zu einem 3D-Bioprinter." Und so entsteht Schicht für Schicht, ganz langsam, ein biologisches Gewebe. Professionelle Gewebezüchter können das auch. Sie benutzen dazu allerdings Hydrogele. Das sind gelatineartige Gerüststrukturen, die den Zellen Halt geben. Die Studierenden vom iGEM-Team der beiden Münchener Universitäten verzichten darauf. Denn der Gerüstbau macht das Drucken aufwendig und kompliziert.

3D-Struktur aus lebenden Zellen

Sie haben stattdessen eine spezielle Bio-Tinte für den 3D-Druck entwickelt. Ein Bestandteil ist der Stoff Biotin, der auch als Vitamin B7 bekannt ist. Er soll in Kontakt mit den Zellen treten. Eine andere Substanz in der Bio-Tinte heißt Streptavidin. Das Protein bindet Biotin und funktioniert wie ein Klebstoff. Außerdem haben die Studierenden Zellen von Bakterien und Säugetieren so verändert, dass sie auf ihren Oberflächen spezielle Biotin-bindende Rezeptoren bilden, erklärt Krumwiede: "Das alles soll dann miteinander quervernetzen, da Streptavidin die Bindungsstellen für Biotin hat, und Biotin an unseren Rezeptor binden kann. Das soll dann polymerisieren und eine 3D-Struktur ausbilden." Der biotINK-Gewebedrucker druckt mit einer Kanüle Gewebe in eine kleine Petrischale (Andreas Heddergott/ TU München) Der biotINK-Gewebedrucker druckt mit einer Kanüle Gewebe in eine kleine Petrischale (Andreas Heddergott/ TU München) Aus Zellen und Bio-Tinte entsteht im 3D-Drucker ein Gewebe aus lebenden Zellen. Fertig für die Transplantation. Das Konzept klingt überzeugend, und so rechnet sich das iGEM-Team aus München selbstbewusst gute Chancen aus beim großen Finale in Boston. Luisa Krumwiede: "Also wenn ich nicht glauben würde, dass wir eine Chance hätten, dann würde ich auch gar nicht hinfahren."

Krebszellen durch Optogenetik ausschalten

Die Universität Düsseldorf ist zum ersten Mal mit einem Team am iGEM-Wettbewerb beteiligt. Die Initiative ging dabei von den Studierenden selbst aus. Ihre Internetseite verrät die großen Ambitionen: Stell dir vor, du drehst einen Schalter, und der Krebs ist weg. "Also uns ist aufgefallen, dass wir alle jemanden kennen, der von Krebs betroffen ist, und da haben wir uns überlegt, dass wir als Biologen da unbedingt etwas dran ändern sollten." Julian Ohl ist einer von 19 Studierenden, die am Projekt mitgearbeitet haben. Trotz wenig Laborerfahrung gelang es ihnen zwei hochaktuelle Forschungsrichtungen zu verknüpfen - mit dem Ziel, eine wirksame Krebstherapie mit möglichst wenigen Nebenwirkungen zu entwickeln: "Der Ansatz ist, dass wir uns optogenetischer Schalter bedienen. Das sind Proteine aus Pflanzen, die wir in den menschlichen Körper einbringen, und zwar gezielt in Krebszellen, und dort dann mit Licht bestrahlen. Das heißt wir benutzen Optogenetik, so heißt das Feld, wenn man mit Licht Proteine anschalten kann, und dadurch wird dann in Krebszellen gezielt der Zelltod eingeleitet."

Das Licht über Glasfaserkabel zum Krebs zu führen

Im Labor ging es zunächst darum, die optogenetischen Schalter in Zellen einzubauen. Sobald nun rotes Licht auf die Zellen trifft, entsteht ein Proteinkonstrukt, das den Zelltod auslösen kann. Anschließend muss noch blaues Licht hinzukommen. Es sorgt dafür, dass das Konstrukt zu den Mitochondrien gelangt. Erst dort kann es seine für Krebszellen tödliche Wirkung entfalten, erläutert Teammitglied Alina Kuklinski: "Unser jetziger Standpunkt ist, dass wir unsere Konstrukte gebaut haben - sowohl der rote als auch der blaue Lichtschalter. Unsere Konstrukte sind nun bereit, nach Boston geschickt zu werden." Noch nicht bei Krebs, aber in Zellkulturen mit Säugetierzellen haben die Studierenden das Prinzip erfolgreich getestet. Um es im menschlichen Körper einzusetzen, müssen das rote und das blaue Licht zum Krebs gelangen - zum Beispiel über feine Glasfaserkabel. Wissenschaftler arbeiten bereits an solchen Verfahren. Aber das ist nicht mehr Aufgabe des Düsseldorfer iGEM-Teams. Die Studierenden machen sich mit ihren Ergebnissen auf den Weg zum großen Finale nach Boston.

"Jetzt wird noch einmal Vollgas gegeben. Und wir sind auf jeden Fall glücklich, was wir bereits erreicht haben", sagt Kuklinski."Bayerischer Rundfunk: "Lebendes Gewebe aus dem 3-D-Drucker"

[http://www.br.de/mediathek/video/sendungen/nachrichten/skerra-drucker-medizin-100.html Weblink to the article]

Münchner Unis wollen Organe drucken

Studenten der beiden Münchner Universitäten TU und LMU haben einen renommierten Wettbewerb gewonnen. Am MIT in Cambridge, MA wurden sie für den 3D-Druck von lebendigem Gewebe ausgezeichnet.

Die Studierenden gewannen einen ersten Preis beim iGEM-Wettbewerb (international Genetically Engineered Machine), einer Art Weltmeisterschaft der synthetischen Biologie. Für den Druck von räumlichem Strukturen mit lebendigem Material bauten sie einen handelsüblichen 3D-Printer um: Statt mit flüssigem Plastik druckten sie mit Zellen.

Meniskus aus dem Drucker

Bereits üblich ist es, mit nicht lebendem biologischen Material zu drucken, beispielsweise mit Knorpel. Auch Gewebe wird schon seit geraumer Zeit gezüchtet und dreidimensional in Form gebracht. Allerdings wird dabei erst ein Gerüst aus so genannten Hydrogelen gebaut, was sehr aufwändig ist. Und erst danach wird dieses Gerüst mit lebendigen Zellen besiedelt.

Einsatz in der Transplantationsmedizin

Websites

Synbiobeta.com: "iGEM Rocks the World Once Again"

[http://synbiobeta.com/news/igem-rocks-world/] File:Muc Synbiobeta.pdf

"This year, 273 teams coming from 6 continents attended the iGEM Giant Jamboree. The energy was electrifying as students buzzed around, setting up their posters, stressing about their presentations, and forging friendships across nationalities that will last a lifetime!

iGEM, for international Genetically Engineered Machine, is the premier global synthetic biology competition. Started in 2004, iGEM brings together teams of 2-20 students from across the world who spend the entire summer building a synthetic biology project that will save the world. These teams construct and assemble specific gene sequences called biobricks that code for particular traits into genetic circuits that cause the cell to perform some novel function.

A classic example is to create an arsenic biosensor by assembling the gene that detects arsenic with the gene that fluoresces and uploading that into the cell, so whenever the cell detects arsenic it will light up. Biosensors are just one example, however; these teams build projects that span the gamut of industries and applications, including within health, energy, architecture, and much more. All the iGEM tracks are listed here.

For 3 days straight, these teams are presenting their projects to a panel of 6 judges who will score them based on their presentation, their posters, and their wikis (the online repository of the team’s entire project). Every year, these projects become more robust, more creative, and more impressive. Furthermore, you start to see themes starting to emerge within the projects; in 2013, CRISPR was all the rage!

This year, however, I began to see a couple teams focusing on audiogenetics, or the ability to induce signal transduction using sound. Two teams, Slovenia and SUSTech Shenzhen, engineered proteins that detected pressure into the cell so that the cells could respond to ultrasound. Imagine delivering a payload of these cells into your bloodstream and being able to activate them in very specific regions of your body just by focusing an ultrasound on that particular region. This could become a powerful tool in targeted drug delivery.

The three winners for this year’s competition were HSi Taiwan for the High School track, Imperial College for the Undergraduate track, and LMU-TUM Munich for the Overgraduate track.

HSi Taiwan developed a test to determine the presence of toxins in traditional Chinese medicines. They recognized that because Chinese medicine fell somewhere between herbal supplements and actual medicine, it was a grey area for regulation and therefore the source and quality is not properly scrutinized. Not only did these high school students create sensors that could detect lead, copper, arsenic, and aflatoxin, but they also designed and built a physical device for the consumer to actually test their medicines, shown in the picture below.

Imperial College London worked on developing a communication system between cells, called quorum sensing, “to maintain stable coexistence of different cell types and allow the ratio of different populations to be stably maintained.” No biological process lives in isolation. Not only are cells able to sense their own growth and culture conditions, but they are inextricably intertwined with different species that make up their ecosystem. Take our microbiome, for example: a healthy microbiome contains a range of microbial species, however, those different species must maintain a proper ratio to be balanced. The ability to grow different populations of cells together will give us an insight in understanding how natural cellular systems work together, as well as allow us to build more complex systems and circuits.

Lastly, LMU-TUM Munich began to tackle the problem of an increasing organ shortage by building a 3D bioprinter with the goal of one day printing out organs de novo. The team repurposed an Ultimaker2 3D printer by building a new extrusion nozzle for it that can deliver a precise flow of liquid containing both the matrix and the cells. However, what made this team shine is not the printer that they built, but the approach they took to solve the scaffolding problem.

Currently, bioprinters rely on scaffolds to form the base on which cells are seeded. This presents many difficulties, including the need to assemble multiple 2D scaffolds to create a 3D object like an organ, then the subsequent dissolution of the scaffold to leave only the cells. This process makes 3D bioprinting cumbersome and expensive. Munich’s solution to this problem is to allow the cells to bind to each other immediately upon printing so that the cells themselves are structurally sound and are without need for a scaffold.

As a judge, I believe what made these projects extraordinary, and what earned them the title of iGEM World Champions, was not only their ambition, nor their progress on accomplishing that ambition (although that certainly counts for a lot). It was the thoroughness in which they completed the project; these teams included everything from hard-core mathematical modeling to an analysis of the impact of their project on the world. It was their clarity in presenting their complex projects. It was their competence when answering tough questions that judges threw at them.

This is my 5th year of participating in iGEM- 2 as a member, 1 as an advisor, and 2 as a judge- and I am proud to see this organization continue to excel at developing both the talent and the foundational repository of data necessary for the synthetic biology revolution.

The syringe pump is the main part of their printer extension. Its purpose is to deliver a precise and constant volume flow of liquid according to the printer's information.

By Shaun Moshasha| November 9th, 2016"wired.de: "Münchner Studierende kommen dem gedruckten Herzen einen Schritt naeher"

[1]

File:Muc Wired.pdf

"Tausende Patienten warten darauf: 3D-Printer, die ganze Organe drucken können – nicht aus Plastik, sondern aus lebenden Zellen. Studierende aus München sind dieser Technologie jetzt einen großen Schritt näher gekommen.

2016 haben die Deutschen bisher 2.383 Organe gespendet – auf den Wartelisten stehen mehr als 10.000 Patienten und Patientinnen. Ein gefährliches Ungleichgewicht – Wissenschaftler weltweit erforschen aber gerade eine Technologie, die Abhilfe schaffen könnte: 3D-Bioprinting. Die Idee: Organe aus dem 3D-Drucker könnten Organspenden überflüssig machen. Einer der vielversprechensten Ansätze kommt aus Bayern.

In nur sechs Monaten haben Studierende der TU und LMU München eine eigene neue Druckertechnologie entwickelt, getestet und umgesetzt. Mit ihrem BiotINK-Gewebedrucker haben sie sogar den prestigeträchtigen Wettbewerb „international Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM)“ gewonnen – und sind dem gedruckten Organ so einen großen Schritt näher gekommen.

Die entscheidende Neuerung: Das Münchner iGEM-Team hat einen Weg gefunden, die Zellen beim Drucken direkt miteinander zu verbinden. Bisher funktioniert Gewebe-3D-Druck vor allem so: Man nimmt ein Gerüst aus Hydrogel und „bevölkert“ es mit lebenden Zellen, die sich vernetzen. Anschließend wird das Hydrogel aufgelöst. „Dieser Auflösungsprozess bedeutet für die Zellen allerdings sehr viel Stress und ist nicht gut für ihre Überlebensfähigkeit“, sagt Clemens Ries, der an der TU München Biologie im Master studiert. Statt Hydrogels zu verwenden, haben Ries und seine Kommilitonen die Zellen deshalb genetisch verändert.

Im Grunde haben sie die Zellwände mit kleinen Haken versehen, damit diese sich besser zu Komplexen zusammenfügen können. Dazu nutzten sie das Protein Streptavidin. Mit der Hilfe eines Moleküls auf den Zellwänden, das sich mit diesem Haken verbindet, lassen sich die Zellen miteinander koppeln.

BioM Biotech Cluster Development

Biotechnologie.de: "Team Muenchen: Mit Bio-Tinte zum iGEM-Champion 2016"

File:Muc Biotechnologiede 001.pdf

Team München: Mit Bio-Tinte zum iGEM-Champion 2016

"Am Ende landete das Team München ganz oben auf dem Siegertreppchen. Über 300 Studenten-Teams aus aller Welt waren in Boston beim iGEM-Finale versammelt. Am Ende landete das Team München ganz oben auf dem Siegertreppchen - es hatte mit einer Biotinte für einen Zell-3D-Drucker gepunktet.

Zünftiger Jubel in Boston: Beim Finale des studentischen Bioingenieur-Wettbewerbs iGEM hat das Team München den Gesamtsieg in der Kategorie „Overgraduate“ abgeräumt. Das Doppelteam von TU München und Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) konnte mit einem 3D-Zelldrucker und passender Bio-Tinte die Fachjury am deutlichsten überzeugen. Mehr als 300 Hochschulteams aus aller Welt hatten beim „Giant Jamboree“ ihre Projekte zur Synthetischen Biologie präsentiert. Die deutschen Teams kehren mit reichlich Medaillen und Titeln von dem Megaevent an der US-Ostküste zurück: Für die 13 hiesigen Teams gab es fünfmal Gold, sechsmal Silber und zweimal Bronze. Das Team Hamburg sahnte zudem den begehrten „iGEMers Prize“ ab, der von den Teilnehmern vergeben wird.

Damit geht die begehrte iGEM-Trophäe, der silberne Riesen-Legostein, wieder einmal nach Deutschland. In den vergangenen Jahren war insbesondere Team Heidelberg mit dem Double 2013 und 2014 bei der Bio-Konstrukteurs-WM in Boston das Maß der Dinge gewesen, in diesem Jahr waren die Badener jedoch nicht angetreten. Team München überzeugte in der Ü23-Kategorie diesmal auf ganzer Linie. Die Studierenden, traditionell mit Dirndl und Lederhosen auf der Bühne, hatten für einen 3D-Drucker eine neuartige Biotech-Tinte (biotINK) aus Zellen kreiert. Dank einer raffinierten molekularen Klebetechnik gelingt es damit, einfache Gewebestrukturen auf Oberflächen zu drucken.

Mit ihrem Projekt verwiesen die Münchener die enorme Konkurrenz auf die Plätze. Auf Rang zwei in der Gesamtwertung von iGEM landete das Team der Uni Wageningen mit einem Bienenschutzmittel gegen die Varroa-Milbe. Neben einer Goldmedaille heimste das TUM-LMU-Team auch noch Extra-Titel für „Best Hardware“, „Best Software“ und das „Best manufacturing project“ ein.

Londoner Team konstruiert Co-Kulturen

Auch in der Kategorie „Undergraduate“ (U23) war ein europäisches Team bei iGEM erfolgreich. Hier verbuchte das Team vom Imperial College London den Gesamtsieg für sich. Die Londoner haben sich in ihrem Projekt „Ecolibrium“ mit der Konstruktion von mikrobiellen Ökosystemen im Labor beschäftigt. Auf den Plätzen folgen das Team Sydney und SCAU-China.

Einen Sonderpreis heimste das Team Hamburg ein. Für die Hanseaten gab es den begehrten „iGEMers Prize“, der von den tausenden Teilnehmern des "Giant Jamborees" als Publikumspreis vergeben wird. Das Projekt "Finding Clamydory" - dessen Website-Gestaltung an den Kinoblockbuster "Finding Dory" angelehnt ist, traf offenkundig den Nerv des Plenums. Das Team hat einen Biosensor entwickelt, der Erreger der Art Chlamydia trachomatis gezielt aufspüren kann. Chlamydien sind Auslöser von Geschlechtskrankheiten, sie werden meist ungezielt mit Breitband-Antibiotika behandelt. Ein präzises Testverfahren, wie die Hanseaten es ausgetüftelt haben, könnte die Therapie verbessern.

Reichlich Edelmetall

Auch der Medaillenspiegel der deutschen Teams ist einmal mehr beeindruckend: Es gab fünfmal Gold (Aachen, Bielefeld, Düsseldorf, Freiburg und München), sechsmal Silber (Bonn, Darmstadt, Nürnberg-Erlangen, Göttingen, Hamburg und Marburg) und zweimal Bronze (Hannover und Tübingen). Damit haben die deutschen Hochschulteams die seit vielen Jahren äußerst erfolgreiche iGEM-Geschichte fortgeschrieben. Hier können Sie die Projekte der Saison 2016 im Kurzprofil nachlesen (mehr...).

© biotechnologie.de/pg"Biooekonomie.de - "iGEM-Finale: Auf Titeljagd in Boston"

File:Muc Biooekonomiede 001.pdf

"iGEM: Team München siegt mit Zell-Tinte

Triumph beim studentischen Bioingenieur-Wettbewerb iGEM in Boston: Das Team aus München hat mit seinem Zell-3D-Drucker den Gesamtsieg abgeräumt.

Riesen-Legostein nach München geholt

Die 13 deutschen Teams kehren mit reichlich Medaillen und Titeln von dem Megaevent an der US-Ostküste zurück: Für die hiesigen Teams gab es fünfmal Gold, sechsmal Silber und zweimal Bronze. Das Team Hamburg sahnte zudem den begehrten „iGEMers Prize“ ab, der von den Teilnehmern vergeben wird.

Damit geht die begehrte iGEM-Trophäe, der silberne Riesen-Legostein, wieder einmal nach Deutschland. In den Jahren 2013 und 2014 standen die iGEMer aus Heidelberg ganz oben auf dem Treppchen der akademischen "Bio-Konstrukteurs-WM". Team München überzeugte in der Ü23-Kategorie "Overgraduate" diesmal auf ganzer Linie. Die Studierenden, in Boston traditionell in Dirndl und Lederhosen unterwegs, hatten für einen 3D-Drucker eine neuartige Biotech-Tinte (biotINK) aus Zellen kreiert. Dank einer raffinierten molekularen Klebetechnik gelingt es damit, Zellen stabil und gezielt auf Oberflächen zu drucken und somit 3D-Gewebe herzustellen.

Mit ihrem Projekt verwiesen die Münchener die enorme Konkurrenz auf die Plätze. Auf Rang zwei in der Gesamtwertung von iGEM landete das Team der Uni Wageningen mit einem Bienenschutzmittel gegen die Varroa-Milbe. Neben einer Goldmedaille wurde das TUM-LMU-Team auch noch mit Sonderpreisen für „Best Hardware“, „Best Software“ und das „Best manufacturing project“ ausgezeichnet.

Hamburger Team wurde Publikumsliebling

Auch in der Kategorie „Undergraduate“ (U23) war ein europäisches Team bei iGEM erfolgreich. Hier verbuchte das Team vom Imperial College London den Gesamtsieg für sich. Die Londoner haben sich in ihrem Projekt „Ecolibrium“ mit der Konstruktion von mikrobiellen Ökosystemen im Labor beschäftigt. Auf den Plätzen folgen das Team Sydney und SCAU-China. Einen Sonderpreis heimste das Team Hamburg ein. Für die Hanseaten gab es den begehrten „iGEMers Prize“, der von den tausenden Teilnehmern des "Giant Jamboree" als Publikumspreis vergeben wird. Das Projekt "Finding Clamydory" - dessen Website-Gestaltung an den Kinoblockbuster "Finding Dory" angelehnt ist, war offenkundig ganz nach Geschmack des Plenums. Das Team hat einen Biosensor entwickelt, der Erreger der Art Chlamydia trachomatis gezielt aufspüren kann. Chlamydien sind Auslöser von Geschlechtskrankheiten, sie werden meist ungezielt mit Breitband-Antibiotika behandelt. Ein präzises Testverfahren, wie die Hanseaten es ausgetüftelt haben, könnte die Therapie verbessern.

Viel Edelmetall für die deutschen Teams

Auch der Medaillenspiegel der deutschen Teams ist einmal mehr beeindruckend: Es gab fünfmal Gold (Aachen, Bielefeld, Düsseldorf, Freiburg und München), sechsmal Silber (Bonn, Darmstadt, Nürnberg-Erlangen, Göttingen, Hamburg und Marburg) und zweimal Bronze (Hannover und Tübingen). Damit haben die deutschen Hochschulteams die seit vielen Jahren äußerst erfolgreiche iGEM-Geschichte fortgeschrieben. Hier kann man die Projekte aus der Saison 2016 im Kurzprofil nachlesen. pg"3dnatives.com - "BiotINK: Bio-3D-Druck für zu Hause mit einem Ultimaker2"

File:Muc 3dnatives 001.pdf "Forscher der Technischen Universität München haben vor kurzem das BiotINK-Projekt vorgestellt, das die Herstellung von komplexen Zellstrukturen erleichtert und beschleunigt. Als Druckmaterial wird Biotin (Vitamin B7) und Streptavidin auf einem zum Biodrucker umfunktionierten Desktop-3D-Drucker zur Herstellung von lebenden Geweben verwendet.

Das bisherige Verfahren zum 3D-Druck von lebendem Gewebe ist das, was Wissenschaftler „Gerüst“ nennen: Die platzierten Zellen entwicklen sich entlang vorgedruckter Strukturen aus PLA. Diese Strukturen sind die Grundlage, auf der sich die organischen Zellen reproduzieren und zu einem Gewebe entwickeln. Das Gerüst wird dann anschließend entfernt, sodass sich das Gewebe selbst zusammen hält. Die Verwendung von Supportmaterial für die Entwicklung von Geweben war die bisher traditionelle Art, mit der gearbeitet wurde, um Gewebe zu Erstellen. Vor ein paar Monaten erfolgten Versuche zur Herstellung einer menschliche Leber aus Stammzellen mit dem gleichen Prozess. Der Nachteil ist, dass die Zellreifung mit der Gerüsttechnik eine lange Zeit beansprucht und sehr teuer ist. Zusätzlich bestehen Beschränkungen in der Größe des Druckobjekts.

„Durch die Verwendung eines Zweikomponentensystems aus gentechnisch hergestellten Zellen und Proteinen schaffen wir eine Art molekularen Superkleber, der eine präzise Positionierung von Zellen durch Bioprinting ermöglicht, während sie in ihrer Position fixiert werden, wodurch die Bildung dreidimensionaler interzellulärer Kontakte und physiologischer Mikroumgebungen ermöglicht wird“, sagt das Team des BiotINK-Projekts.

Die BiotINK-Forscher funktionierten dazu einen normalen Ultimaker 2 zu einem Biodrucker um. Der Extruder wurde durch eine Spritzpumpe ersetzt, damit Zellen auf die vorprogrammierten Stellen mikrometergenau positioniert werden können. Nachdem sie den Drucker hatten, mussten sie sich an die Entwicklung eines geeigneten Biomaterials machen, das nicht nur ohne Gerüst arbeitet, sondern auch den verschiedenen Eigenschaften komplexer Zellstrukturen gerecht wird.

Das erstaunliche an der Sache ist, dass alles und jedem zu Verfügung steht. Mit einem Wiki auf ihrer Homepage ist alles von der Umfunktionierung des 3D-Druckers zu einem Bio-3D-Drucker bis zur verwendeten Biotinte alles erklärt. Mit voller Transparenz wird jeder dazu eingeladen an dem Open-Source Projekt teilzunehmen, um gemeinsam schneller Erfolge zu realisieren."3dprintingindustry.com - "BiotINK: Now you can print tissue with your own 3D printer"

File:Muc 3dprintingindustry 001.pdf "Researchers at the Germany’s Technical University of Munich presented their biotINK project at the International Genetically Engineered Machine 2016 Giant Jamboree in Boston on October 29. BiotINK aims to make printing complex 3D cellular structures cheaper, easier and faster by using a new technique that creates inks using biotin (vitamin B7) and streptavidin, a protein harvested from bacteria.

The Issue with Tissue

The traditional process for growing artificial tissue relies on scaffolding, since this technique allows cells to be held in place while they develop. In this process the 3D printed grid like structure, made of PLA normally, is seeded with organic cells that slowly grow throughout all the structure filling all the internal spaces. As the organic cells multiply, eventually the scaffold degrades or is removed, leaving behind only the organic tissue.

There have been recent advances this bioprinting method, such as a new proposal for bioreactors from Greek scientists. In any case, scaffolding has its limitations; it is costly, the cell maturation process takes a long time and has certain size limitations.

Team Munich’s Idea

The researchers, lead by Dr. Arne Skerra, propose a new method using desktop 3D printers to print organic 3D cellular structures. The method arranges two different type of components (genetically engineered cells and proteins) into a structure that quickly polymerizes creating a rigid structure. This two components are linked by a very strong bonding reaction, also found in nature, called the biotin-streptavidin interaction.

Bioprinting, one step closer

Bioprinting is an sector of 3D printing that has many potential applications in the health research field. Among them, testing and experimentation for medical studies is a particular field where tissue engineering is crucial, for example as reported by 3DPI the latest advancements from a team at Harvard. This particular application for tissue engineering allows a faster understanding of human diseases, improving the rate at which scientists develop potential cures.

Perhaps a key to the potential success of this project is their openness to the bioprinter community through their website, in which they have documented publicly their project and share instructions to turn your normal 3D printer into a bioprinter. This invitation to collaborate celebrate the internet’s main purpose of being an open communication space, as explored at MozFest last weekend.

Featured image via the Technical University of Munich, by Andreas Heddergott."3dprint.com - "BiotINK: Scaffold Free Bioprinting"

File:Muc 3dprint 001.pdf "3D printed, transplantable, functional human organs are getting closer and closer to becoming a reality, as unbelievable as that seems. While bioprinting technology hasn’t quite gotten to the point of being able to actually 3D print a kidney or liver and implant it into a living human being, it’s only a matter of time as multiple universities, biotechnology companies, and research institutions race to be the first to do so. It’s a fascinating race to watch, not just for the obvious reasons, but because everyone’s technology is a little bit different. Most 3D printed tissue is created by depositing cells onto a scaffold, where they ideally grow into layers of living tissue to be used for research, pharmacological testing, or, ultimately, regenerative medicine. It’s an incredibly tricky process that often fails due to a variety of reasons: the scaffold is too soft and collapses, it degrades too quickly, or it damages or kills the delicate cells. The scaffold also needs to be removed somehow once the tissue has matured, or else to biodegrade safely on its own. Scaffold-free bioprinting is a goal that many researchers have their eyes on, but most bioprinting materials, or bio-inks, aren’t strong enough to hold their structures without support. A team formed from students at Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich and the Technical University of Munich, however, has developed what they hope will be a breakthrough in bioprinting. Team biotINK, formed for the International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition (iGEM), didn’t even require special machinery for their biotINK printing process – just a simple Ultimaker 2+ 3D printer.

The biotINK team hacked their Ultimaker printer by replacing the extruder with a 3D printed syringe pump and programming it to extrude cells with millimeter-level precision. Just about any desktop printer can be inexpensively modified with their method, the team says (you can find detailed instructions on how to do so on Hackaday). Once they had a working bioprinter, the team set about developing a bio-ink that was not only strong enough to grow without a scaffold, but had the properties necessary for the creation of complex tissues with precisely positioned cells and multiple cell types.

The material was devised by combining biotin, also known as vitamin B7, with streptavidin, a protein naturally attracted to biotin molecules that acts as a super-strong binding agent.

The idea is for the streptavidin and biotin to polymerize and form a 3D cellular structure without the need for a scaffold of any kind. Eliminating the scaffold, not to mention being able to use a standard desktop printer to extrude the material, could make 3D bioprinting dramatically less expensive than it is now, as well as faster and simpler.

Of course, no form of 3D bioprinting is exactly simple, but the students have carried out a number of experiments with their Ultimaker-turned-bioprinter and biotin/streptavidin ink, and have gotten some very promising results. One discovery they made was that the viability of cells printed with their technology was close to 100%, as opposed to about 85% with standard inkjet bioprinters and 40-80% with microextrusion bioprinters. After the iGEM competition, which culminates today in a massive showcase of the work of over 300 teams, the biotINK team hopes to meet with investors to discuss a possible new business venture. Armed with a functional prototype and a business plan, the team believes that they could make a real impact on the pharmaceutical industry. Discuss in the biotINK forum at 3DPB.com.

Updated to add: at the iGEM competition, the team won awards for Best Manufacturing and Best Software Tool, and was the Overgrad Grand Prize Winner, as reported on the project’s Twitter page."Social Media

Facebook: SynBio.Info (22 500 followers)

Facebook: Labbiotech.eu (3 900 followers)

Facebook: technologist.eu (2 200 followers)