(→Receptor design highlights) |

|||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

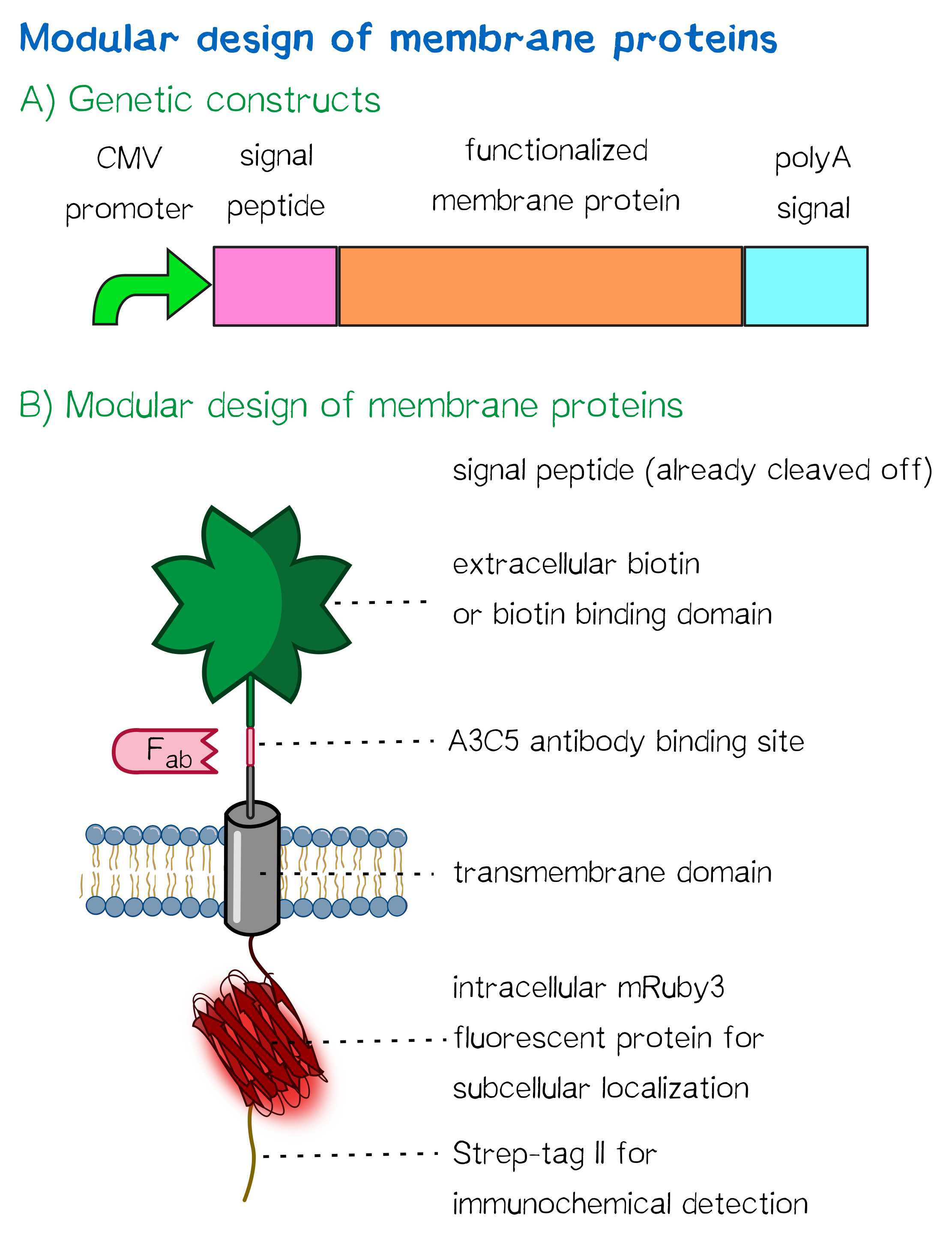

For this purpose we built '''two kinds of receptor constructs''', both on their own being able - when expressed in mammalian cells - to cross-link cells for our very own approach of bioprinting. | For this purpose we built '''two kinds of receptor constructs''', both on their own being able - when expressed in mammalian cells - to cross-link cells for our very own approach of bioprinting. | ||

| − | [[File:Muc16 receptor schematic_002.png|thumb|right|360px|'''Figure 1: (A) | + | [[File:Muc16 receptor schematic_002.png|thumb|right|360px|'''Figure 1: (A) Genetic receptor constructs''' in a schematic representation of functional elements. |

'''B) | '''B) | ||

A receptor containing an extracellular biotin acceptor peptide''' that is endogenously biotinylated by a coexpressed biotin ligase (BirA) and thus presents biotin groups at the cell surface.]] | A receptor containing an extracellular biotin acceptor peptide''' that is endogenously biotinylated by a coexpressed biotin ligase (BirA) and thus presents biotin groups at the cell surface.]] | ||

Revision as of 21:10, 18 October 2016

Receptor design highlights

Think before you ink may be a popular slogan by tattoo adversaries, but it has also been perfectly applicable to creating our synthetic biology approach of bioprinting. In the following, we are going to explore the thought processes that went into the design of the receptors that allow us to embed eukaryotic cells into a stable, three-dimensional and user-definable matrix immediately upon printing.

For this purpose we built two kinds of receptor constructs, both on their own being able - when expressed in mammalian cells - to cross-link cells for our very own approach of bioprinting.

The biotin acceptor peptide (BAP) is a 15 amino acid peptide sequence originating from E. coli. [1] Being biotinylated by the biotin ligase BirA at a lysine residue within the recognition sequence, it mediates the functionality of the receptor by presenting biotin, allowing the interaction of the cell surface with streptavidin in the reservoir solution. The biotin ligase BirA is therefore encoded by the same vector as the receptor, with an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) allowing translation of two open reading frames (ORFs) from a single polycistronic plasmid. BirA is targeted to the ER via an Igκ signal peptide as well as an ER retention signal, allowing it to biotinylate translocating proteins possessing the recognition sequence.

2) Receptors presenting an extracellular, monomeric or single-chain avidin variant.

These avidin derivates, by design, allow the functional fusion of the otherwise tetrameric avidin molecule with our receptor. Two different variants were hereby used: The so-called enhanced monomeric avidin, a single subunit avidin that is able to bind biotin as a monomer, and single-chain avidin, which resembles the naturally occuring avidin tetramer, but has the subunits being connected via polypeptide linkers.

Both receptors generally mediate the same purpose: By interacting with streptavidin in the printing reservoir - either directly by presenting biotin (biotin acceptor-peptide) or indirectly via binding to a biotinylated linker (single chain-avidin variants), cells are being cross-linked due to the polyvalent binding of single streptavidin molecules in the printing solution to several cellular biotin groups at once.

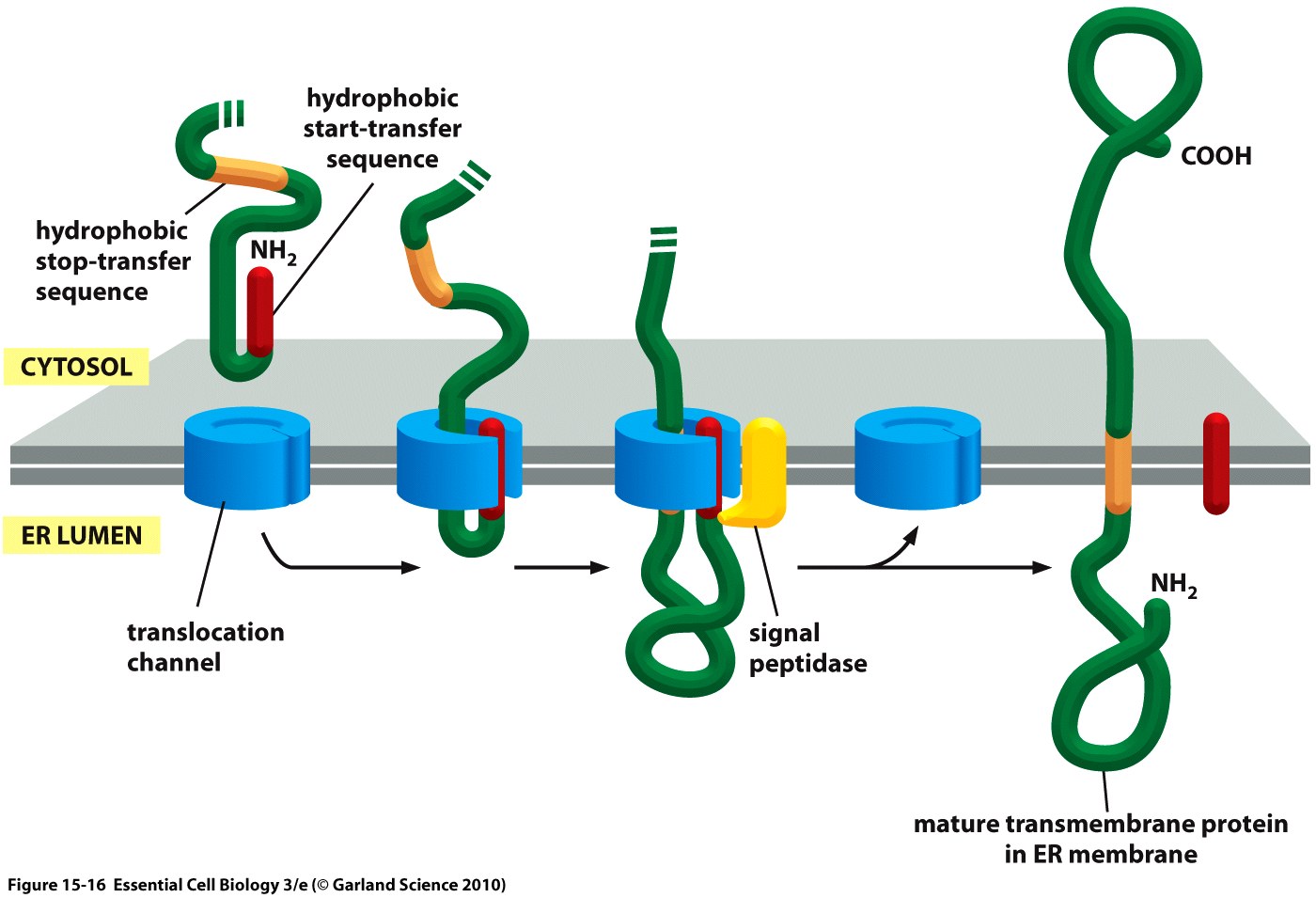

The incredible journey: signal peptides and protein targeting

Essential to a protein's function is not only its activity or binding properties, but also its presence at the right time, at the right place - in our case, the right place being the cell surface. One of the most ubiquitous elements for protein targeting is the signal peptide, which enables the translocation of proteins to the ER, from where their journey may continue to their place of function. Proteins containing a signal peptide include transmembrane proteins, secreted proteins, proteins of the ER itself, proteins of the Golgi apparatus and several more.[2] For our project, signal peptides constitute a crucial part for many constructs, being used for targeting of transmembrane proteins to the cell surface (receptors), targeting proteins to the ER (BirA) and the secretion of proteins into the surrounding medium (luciferase assays for the quantification of expression levels).

The hydrophobic signal peptide (also called start-transfer sequence) usually consists of less than 30 amino acids [4] and is recognized by the signal recognition particle upon translation at the rough ER, mediating the co-translational translocation of the nascent peptide chain into the ER.[5]

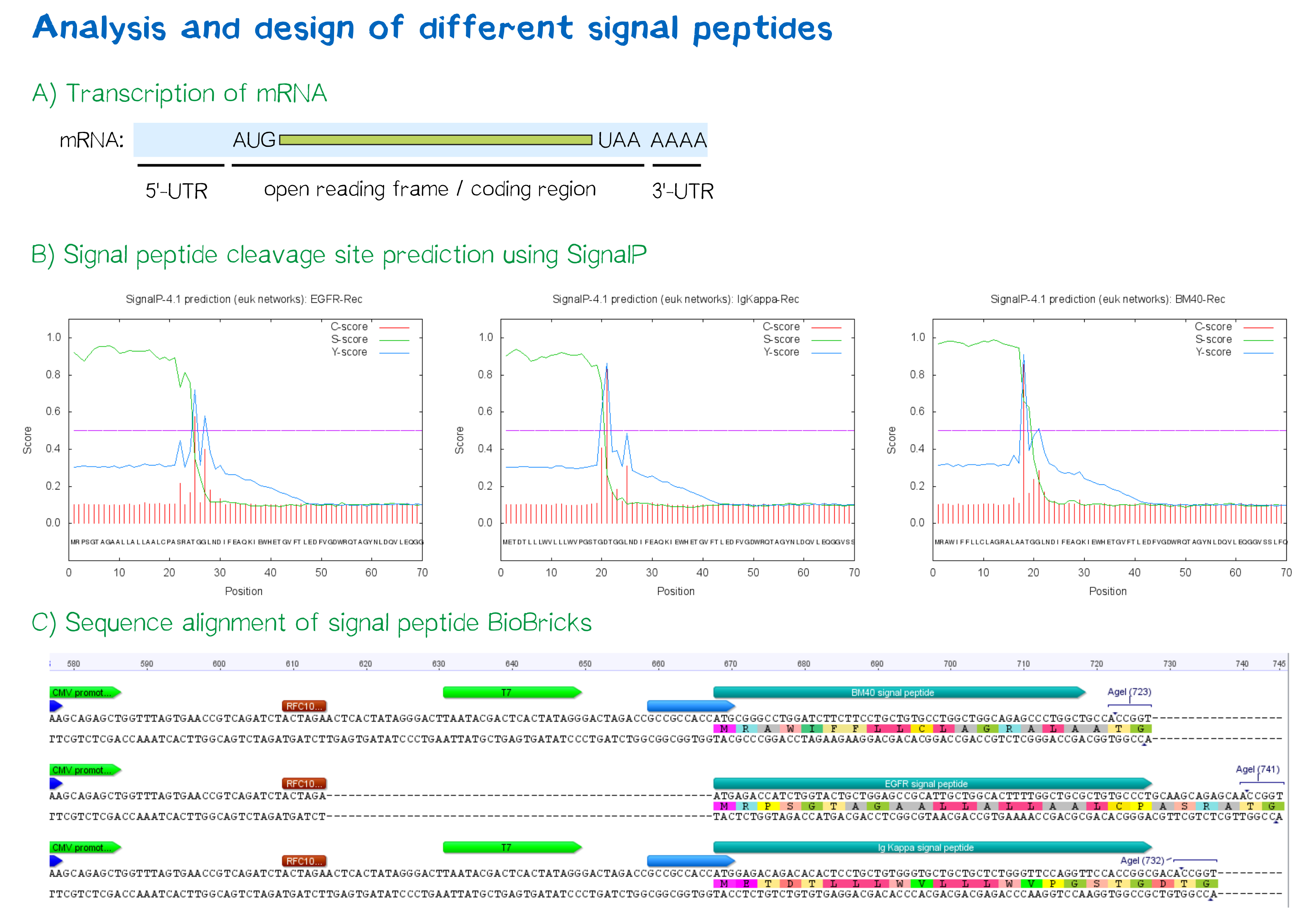

During this project, three different signal peptide constructs are being tested in order to determine the one resulting in the highest expression levels:

- The EGFR signal peptide was taken from the iGEM parts registry ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K157001:Design BBa_K157001]) and combined with a BioBrick containing the CMV promoter sequence ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K747096 BBa_K747096]) via the RFC10 cloning standard.

- The BM40 and Igκ signal peptides were designed by us and synthesized under the aspect of adding additional spacing and functional elements to the 5'-UTR of the constructs, and combined with a BioBrick containing the CMV promoter sequence ([http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_K747096 BBa_K747096]) via the RFC10 cloning standard.

The EGFR signal peptide taken from the parts registry is constructed in a way that the signal peptide ORF immediately follows the RFC10 cloning scar after the CMV promoter, thus resulting in a very short 5’ untranslated region (UTR) of the transcribed mRNA. The combination of the CMV promoter with the synthesized BM40 and Igκ signal peptides allows for a considerably longer 5’-UTR of the resulting mRNA - additionally allowing them to contain a full Kozak consensus sequence by design. The Kozak sequence is recognized by the ribosome as a translational start site; this element missing or deviating from the consensus sequence may considerably decrease translation efficiency.[6] For the EGFR signal peptide construct, a Kozak sequence is not present, as it would have to preceed the start codon ATG - a position which is occupied by the RFC10 cloning scar.

Since both the distance from the promoter to the open reading frame as well as the Kozak consensus sequence are considered crucial parameters for expression levels[7], BM40 and Igκ signal peptide constructs are likely to resut in increased expression levels compared to proteins containing the EGFR signal peptide from the parts registry.

In order to predict whether our designed signal peptides would be functional, we used the [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP SignalP] server, which allows to make theoretical predictions about signal peptide functionality and cleavage.[8]

Other receptor elements: stability and detection

Apart from the functional parts that mediate the (strept)avidin-biotin interaction, other elements in the receptor were designed to make sure it is optimally translocated to the membrane, as stable as possible, and easily detectable.

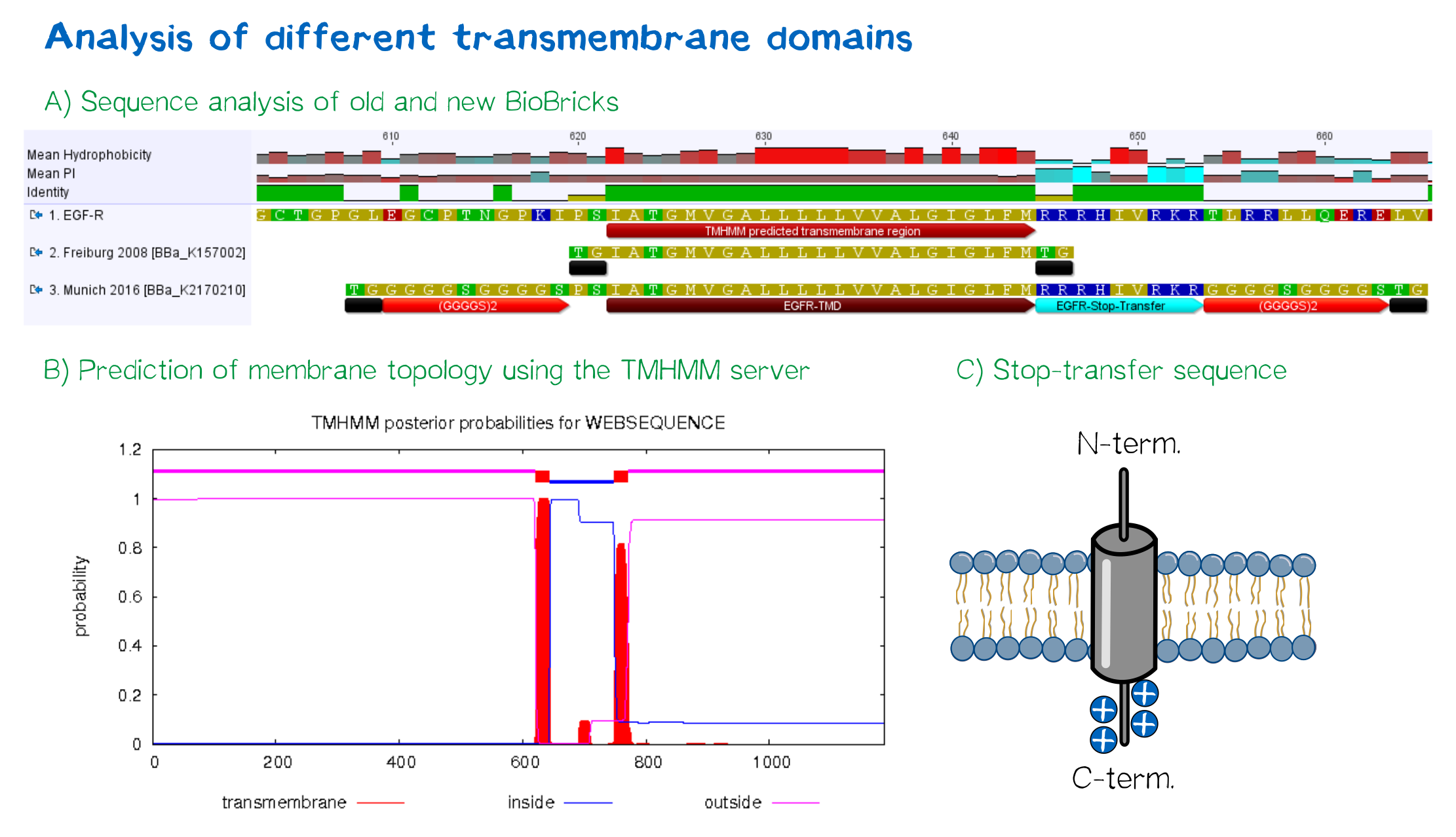

EGFR transmembrane domain

Other receptor elements

Moreover, the receptor contains three functional elements for its detection:

- The intracellularly located red fluorescent protein mRuby 3 for detection of the receptor via fluorescence microscopy,

- an extracellular epitope domain for immunochemical detection via A3C5-antibody fragments and

- an intracellular Strep-tag II for the detection and purification via immunochemical methods.

The vector furthermore contains the CMV promoter for high expression levels, resulting in a high-avidity-interaction, as well as a poly-adenylation signal of human growth hormone (hGH) for functional polyadenylation of the transcribed mRNA.

The final construct

The final expression construct for the eukaryotic cell receptor is shown belown for the receptor with the biotin acceptor peptide (BAP). Other constructs differ from this one by not encoding the eIF4G1-IRES as well as not encoding the biotin ligase BirA. Instead of the biotin acceptor peptide, those constructs encode a monomeric or single-chain avidin variant.

References

- ↑ Chen, I., Howarth, M., Lin, W., & Ting, A. Y. (2005). Site-specific labeling of cell surface proteins with biophysical probes using biotin ligase. Nature methods, 2(2), 99-104.

- ↑ Rapoport, T. A. (2007). Protein translocation across the eukaryotic endoplasmic reticulum and bacterial plasma membranes. Nature, 450(7170), 663-669.

- ↑ Taken from Alberts, B., Bray, D., Hopkin, K., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., ... & Walter, P. (2010). Essential cell biology. Garland Science.

- ↑ Walter, P., Ibrahimi, I., & Blobel, G. U. N. T. E. R. (1981). Translocation of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum. I. Signal recognition protein (SRP) binds to in-vitro-assembled polysomes synthesizing secretory protein. The Journal of Cell Biology, 91(2), 545-550.

- ↑ Keenan, Robert J., et al. "The signal recognition particle." Annual review of biochemistry 70.1 (2001): 755-775.

- ↑ Kozak, M. (1989). The scanning model for translation: an update. The Journal of cell biology, 108(2), 229-241.

- ↑ Kozak, M. (1987). An analysis of 5'-noncoding sequences from 699 vertebrate messenger RNAs. Nucleic acids research, 15(20), 8125-8148.

- ↑ Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G., & Nielsen, H. (2011). SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature methods, 8(10), 785-786.

- ↑ Sonnhammer, E. L., Von Heijne, G., & Krogh, A. (1998, July). A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. In Ismb (Vol. 6, pp. 175-182).