VolkerMorath (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (25 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{LMU-TUM_Munich|navClass= | + | {{LMU-TUM_Munich|navClass=description}} |

| − | < | + | __NOTOC__ |

| + | =<span style="color:#009440">bio(t)</span><span style="color:#3070b3">INK</span> - a synthetic biology approach to bioprinting= | ||

| + | <div class="white-box"> | ||

| + | While interactions between biomolecules make up cellular systems, the three-dimensional organization of cells makes up tissues and organs. For decades, scientists have tried to reconstitute such functional tissues by assembling the cells they are made of – especially for the field of regenerative medicine, where acquiring – or failing to acquire – suitable transplants may mean life or death for the patient. The prospect of creating personalized transplants artificially has since motivated groups all around the world to take part in this endeavour.<ref>Murphy, S. V., & Atala, A. (2014). 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nature biotechnology, 32(8), 773-785.</ref> | ||

| + | Thus, not only could [https://2016.igem.org/Team:LMU-TUM_Munich/Demonstrate bioprinting] prove fruitful in the field of personalized medicine – for pharmacological applications, three-dimensional cell culture systems often constitute the first step in testing a potential pharmacological agent. Systems that resemble the human system as much as possible are especially desirable as they allow for predicting a drug's effect ''in vivo'' more confidently and may furthermore reduce the need for lab animals.<ref>Griffith, L. G., & Swartz, M. A. (2006). Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 7(3), 211-224.</ref> | ||

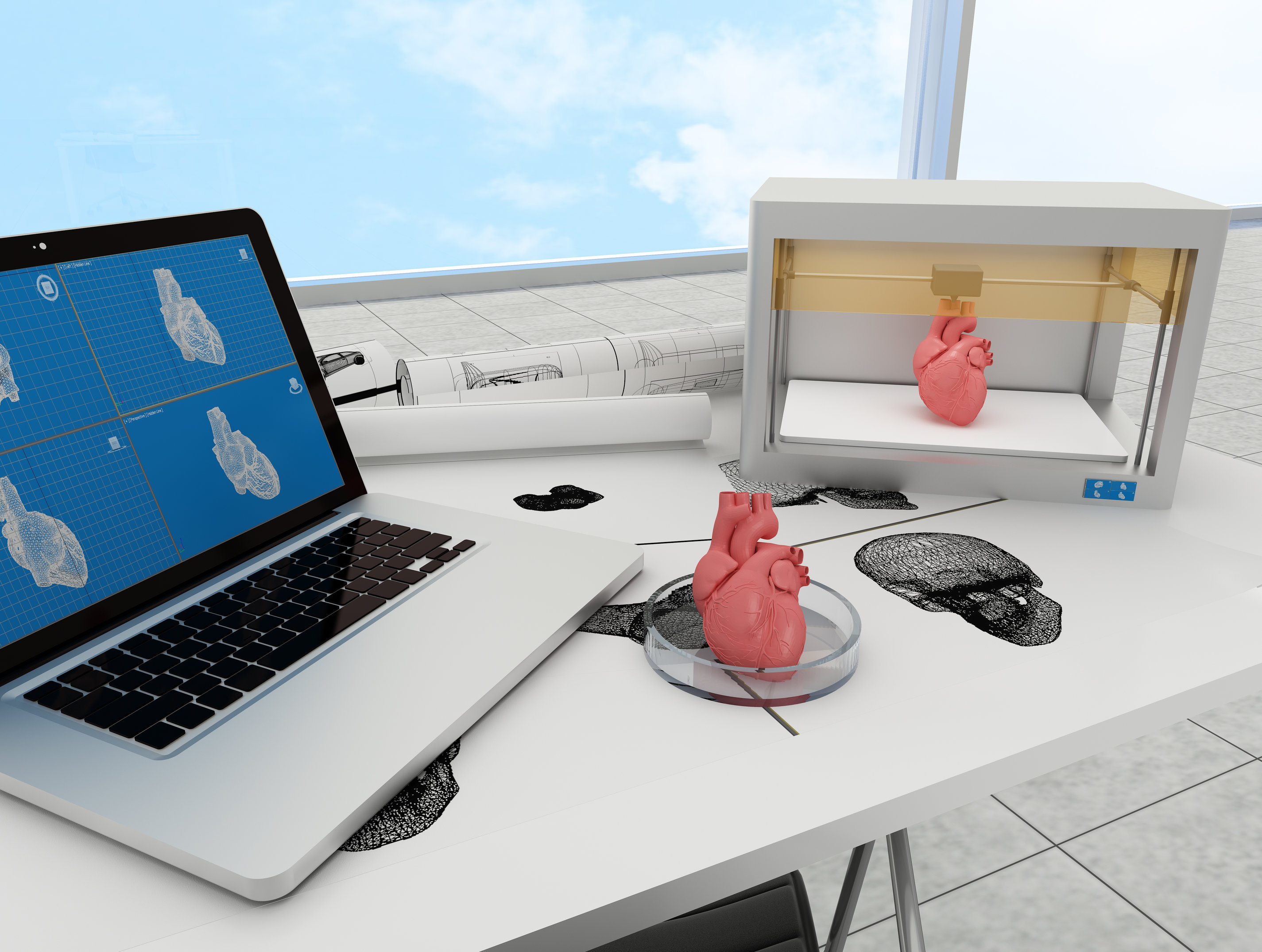

| + | <div class="imagelink float-right">[[Media:Muc16 dafuture.jpeg]][[Image:Muc16 dafuture.jpeg|320px|link=]] | ||

| + | <div class="caption">'''Figure 1:''' A vision of bioprinting in the future: designing and printing whole organs in the lab.</div></div> | ||

| − | + | So far, Bioprinting systems have not been able to distinctly impact either of these fields. Most of the current techniques rely on a scaffold on which cells are seeded. After a certain timespan of ''in vitro'' maturation, cells form intercellular contacts and start to grow into two-dimensional cell layers. To reconstruct the tissue, layers have then to be combined and the scaffold needs to be removed or degraded naturally within the recipient. The technical complexity of the printing process itself makes bioprinting, as it exists now, not only cumbersome but also time-consuming and expensive. Furthermore, the growth of two-dimensional cellular layers does not resemble histogenesis ''in vivo'' and is limited to simple tissues that do not require exact positioning or contain multiple cell types.<ref>Derby, B. (2012). Printing and prototyping of tissues and scaffolds. Science, 338(6109), 921-926.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Our ambitious project intends to eliminate these disadvantages: We are able to [https://2016.igem.org/Team:LMU-TUM_Munich/Proof create three-dimensional cellular structures] easily, quickly and at low cost by immediately cross-linking cells into a protein/cell-matrix upon printing. The interactions of cells with each other and the [https://2016.igem.org/Team:LMU-TUM_Munich/Proteins protein matrix] are mediated by the strongest non-covalent force found in nature – the biotin-streptavidin interaction. In using a two-component system of genetically engineered cells and proteins, we create a "molecular superglue" that allows precise positioning of cells via bioprinting and locking them in position, allowing the formation of three-dimensional intercellular contacts and physiological microenvironments. | ||

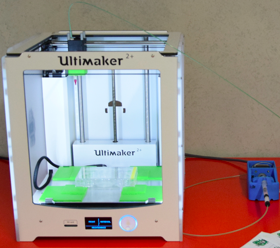

| + | <div class="imagelink float-left">[[Media:Muc16 mahprinter.png]][[Image:Muc16 mahprinter.png|320px|link=]] | ||

| + | <div class="caption">'''Figure 2:''' Our modified 3D-printer to printing genetically engineered cells, enabling the creation of stable cellular matrices.</div></div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | For cell delivery, we [https://2016.igem.org/Team:LMU-TUM_Munich/Hardware hijacked a conventional 3D printer] that can be programmed to inject cells with sub-millimeter precision. Since the cells rapidly polymerize, we achieve a very high spatial resolution. But that's not all: The printing system we created can easily reproduced by any lab around the world provided they have a conventional 3D printer to start with, allowing to print cellular structures as required with only little initial investment. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | Apart from the more medically oriented aspects of regenerative medicine and pharmacology, cellular systems are also of great interest for basic and applied research. While much on the molecular interactions within cells is known, comparatively little is known about the complex interactions of cells with each other. Therefore, by providing a tool to render research on a supercellular scale more accessible, we are convinced that our system is able to noticeably advance science in many areas. | ||

| + | In addition to establishing the <span style="color:#009440">biot</span><span style="color:#3070b3">INK</span> system itself, we have also worked on several ways to functionalize tissue: To create synthetic organs, we modified cells to secrete insulin in response to external stimuli with infrared light. Also, we have worked on inducing vascularization in printed tissue in response to hypoxia. Furthermore, we have also modified our system to work in bacterial cells. | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class=" | + | ==References== |

| − | + | <div class="white-box"> | |

| − | < | + | <references /> |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{LMU-TUM_Munich_html_end}} | {{LMU-TUM_Munich_html_end}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:39, 2 December 2016

bio(t)INK - a synthetic biology approach to bioprinting

While interactions between biomolecules make up cellular systems, the three-dimensional organization of cells makes up tissues and organs. For decades, scientists have tried to reconstitute such functional tissues by assembling the cells they are made of – especially for the field of regenerative medicine, where acquiring – or failing to acquire – suitable transplants may mean life or death for the patient. The prospect of creating personalized transplants artificially has since motivated groups all around the world to take part in this endeavour.[1]

Thus, not only could bioprinting prove fruitful in the field of personalized medicine – for pharmacological applications, three-dimensional cell culture systems often constitute the first step in testing a potential pharmacological agent. Systems that resemble the human system as much as possible are especially desirable as they allow for predicting a drug's effect in vivo more confidently and may furthermore reduce the need for lab animals.[2]

So far, Bioprinting systems have not been able to distinctly impact either of these fields. Most of the current techniques rely on a scaffold on which cells are seeded. After a certain timespan of in vitro maturation, cells form intercellular contacts and start to grow into two-dimensional cell layers. To reconstruct the tissue, layers have then to be combined and the scaffold needs to be removed or degraded naturally within the recipient. The technical complexity of the printing process itself makes bioprinting, as it exists now, not only cumbersome but also time-consuming and expensive. Furthermore, the growth of two-dimensional cellular layers does not resemble histogenesis in vivo and is limited to simple tissues that do not require exact positioning or contain multiple cell types.[3]

Our ambitious project intends to eliminate these disadvantages: We are able to create three-dimensional cellular structures easily, quickly and at low cost by immediately cross-linking cells into a protein/cell-matrix upon printing. The interactions of cells with each other and the protein matrix are mediated by the strongest non-covalent force found in nature – the biotin-streptavidin interaction. In using a two-component system of genetically engineered cells and proteins, we create a "molecular superglue" that allows precise positioning of cells via bioprinting and locking them in position, allowing the formation of three-dimensional intercellular contacts and physiological microenvironments.

For cell delivery, we hijacked a conventional 3D printer that can be programmed to inject cells with sub-millimeter precision. Since the cells rapidly polymerize, we achieve a very high spatial resolution. But that's not all: The printing system we created can easily reproduced by any lab around the world provided they have a conventional 3D printer to start with, allowing to print cellular structures as required with only little initial investment.

Apart from the more medically oriented aspects of regenerative medicine and pharmacology, cellular systems are also of great interest for basic and applied research. While much on the molecular interactions within cells is known, comparatively little is known about the complex interactions of cells with each other. Therefore, by providing a tool to render research on a supercellular scale more accessible, we are convinced that our system is able to noticeably advance science in many areas.

In addition to establishing the biotINK system itself, we have also worked on several ways to functionalize tissue: To create synthetic organs, we modified cells to secrete insulin in response to external stimuli with infrared light. Also, we have worked on inducing vascularization in printed tissue in response to hypoxia. Furthermore, we have also modified our system to work in bacterial cells.

References

- ↑ Murphy, S. V., & Atala, A. (2014). 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nature biotechnology, 32(8), 773-785.

- ↑ Griffith, L. G., & Swartz, M. A. (2006). Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology, 7(3), 211-224.

- ↑ Derby, B. (2012). Printing and prototyping of tissues and scaffolds. Science, 338(6109), 921-926.